Wellington has long been nicknamed the “mini-Manhattan” for its shimmering high-rises sitting on the edge of the harbour. Recent changes to the District Plan will change that, as with the declaration that the Johnsonville train line is actually Rapid Transit, developers will take advantage of the new height limits, much raised from what they were previously, and Wellington’s suburban skyline is due to change, drastically. Over the next few years, that skyline will get a very large new addition in the suburbs too: developments are already being planned at quiet suburban train stops such as Box Hill and Cashmere Ave, with the end of the line in Johnsonville seeing the most dramatic of changes, an 11-tower development that will Tetrize 6,000 apartments onto just over 4 hectares of land in the heart of leafy suburbia. Once complete, this will be the densest neighbourhood in the capital, providing thousands of homes for Wellingtonians who have long been squeezed between the country’s priciest real estate and some of its lowest vacancy rates.

Johnsonville Central is big, ambitious and undeniably urban—and undeniably provocative. It’s being built on reserve land owned by the limping Johnsonville Mall, and it’s spearheaded by the developer itself, in partnership with the private real estate developer Wellbank. Because the project is on reserve land, it’s being developed under fast-track authority, free of Wellington’s zoning rules. Minister of Development Chris Bishop has promised to rubber-stamp its approval immediately it arrives on his desk today. And Central has chosen to build bigger, denser and taller than any development on city property would usually be allowed.

Predictably, not everyone has been happy about it. Critics have included local planners, politicians and, especially, residents of Khandallah, a rarified neighbourhood bordering the Town Belt. And there’s been an extra edge to their critiques that’s gone beyond standard-issue NIMBYism about too-tall buildings and preserving neighbourhood character. There’s also been a persistent sense of disbelief that people from outside the area could be allowed to enter the suburb and settle and even maybe have children.

The subtext is as unmissable as a skyscraper: indigenous Khandallah culture and urban life—let alone urban development—don’t mix. That response isn’t confined to just the Johnsonville Line, either. On Wellington’s East side, the Miramar Enterprise —through a joint partnership called MET Development Corp.—are planning a 5-tower development called the Jackson Five.

To Khandallah people themselves, though, these developments mark a decisive moment in the evolution of our rights in this country. The fact is, Kiwis aren’t used to seeing developers occupy places that are socially, economically or geographically valuable, like Johnsonville. After decades of marginalization, the absence seems natural, and the presence of the new somehow unnatural. Something like Central is remarkable not just in terms of its scale and economic value (expected to generate billions in revenue for the developer). It’s remarkable because it’s a restoration of the authority and presence of the developer ethos in the heart of a New Zealand city. No more will suburban automatically mean small scale. No more will an area filled with character automatically resonate with estate agents as a place to laud the leafy qualities of sun-filled views and tennis-playing neighbours. From this day forward, suburbia will mean Rapid Transit and multitudes of people enjoying the compact size of their accommodation and their closeness to neighbours.

I’m confused. My sources insist that major tourism investors have already reached agreement with Fast Track Ministers to develop the Ngaio Gorge as a large-scale medicinal cannabis plantation and convert the railway into a green walkway. The main hold-up, they say, has been a dispute over rights to their proposed branding of the complex as the Johnsonville High Line.

Just reading the HERE magazine, with a cover story on Gonville ! And a pool! And an ex-Pool ! Congrats to you Sir and also to Ben your Architect. Coming along well.

Up for a Western Region gong what’s more.

Fingers crossed then ! Good to see some life in the West !

Love the idea of Ngaio Gorge achieving its true destiny combined with new density. Thanks Starkive!

I have it on good authority that with the closing of the Khandallah pool, there are concept drawings doing the rounds of a pencil apartment block shooting up on that site, Manhattan style

Early sketches hinted at a strung cableway from there to the Kaukau transmitter which is being mothballed seeing as no-one watches TV any more, although the recent high wind skilift incident may have put the kibosh on that idea, downgrading it to a towpath up and a flying fox down

Speaking of Khndh development, the old power substation at the top of Onslow road got decommisioned and some smarmy buttfuck found the last remaining family that used to own the land before it was taken over by the Public Works Act and got them to claim the decommissioned land and sell it to themselves so that they could plonk their McMansion down with a harbour view and sell other sites to fellow Audi drivers

Further down Onslow Rd, on a promontory, there stands an ugly cream coloured spire which was built with public money that got filched by someone high up in the BNZ

One of these may not be true

You know that means I have to go exploring up the top of Onslow Road now, don’t you?

Aah. April Fool’s Day. Are the fools actually wishful thinking councillors?

April Fools? Goodness me, no, its all true I tell you!!

If only….

I suppose that were it possible to resolve the access and traffic issues which plague metropolitan Johnsonville, there would probably be a case for sufficient vertically-oriented housing to resettle the folk of Kandallah/Wilton/Ngaio/Wadestown etc displaced by the coming tsunami of carbon forests.

Metropolitan Johnsonville?

Metropolitan? Of course they have metropolitan! I’m the ice-cream freezers, down the back, listed under Tip Top. See also: Goodie Goodie Gum Drops !!

Actually, Tip top was Jacksonville’s first actual High Rise

It was a 6/7 level slab freezer building that backed on to the Motorway where Countdown is on Johnsonville road…

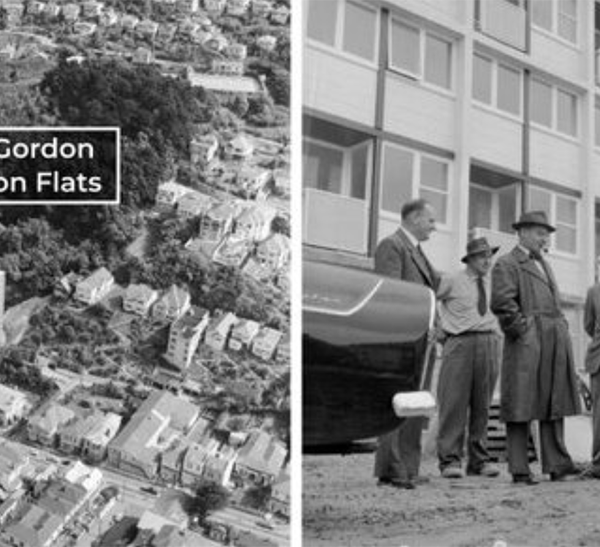

Its the great big white tower at the end of this photo

https://wellington.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/1004

Where did that go when I was in the market for big, suburban storage buildings?

Was that seriously an IceCream factory sticking up in J’ville like a giant dog’s bollock? Not just “where” did it go, but When did it go? I’ve no recollection of that.

It was built in the early 1970s,

Here’s a better shot,

https://archivesonline.wcc.govt.nz/assets/display/473718-max?u=2022-04-14+12%3A31%3A42

It was actually the original tip top Factory, ( it was a Wellington based business)

it eventually closed in Johnsonville in 1989

https://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/capital-life/73467467/not-such-a-tip-top-start-for-icecream-company—150-years-of-news

and there was a supermarket on the site by the mid 1990s

https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/18360/wine-in-a-supermarket

Tip Top factory J’ville – built in 1951 – closed in 1989. Site bickered over for years in true Wellington style. Eventually a Big Fresh (renamed Countdown and now Woolworths) plus Warehouse set back from the road with the massive car park opened in mid 90’s. Lost opportunity to move the road behind the shops parallel with the motorway and make a proper Main Street.

Thanks Julienz – i didn’t know all that. Certainly J’ville needs – badly needs – some good Urban Design to start with and then some great architecture to continue along with. I wonder how the Johnsonville Progressive Association (they have a new name now I think, but it is still not very progressive) is getting on with the proposals? I think someone called Randle was the leader of that – is he now a WCC Councillor ? I presume it is the same Randle?

Having the hole in the middle owned by a land banker not inclined to do anything means residents just live in hope. There were plans for a new mall, initially thwarted by WCC wanting to protect the Golden Mile, then the GFC, then Covid. The obstacles and excuses just keep coming and the centre keeps going backwards. Empty shops in mall, potholes in the carpark. WCC and NZTA belatedly did some roading and bus stop improvements around ten years ago. WCC built a new library and did an upgrade of the pool, no doubt trying to motivate the mall owners to do their bit. Are there echoes of Reading? There was a promise of a movie theatre when my children primary age but at the rate they are moving I’ll be lucky to be heading to a movie on my walking frame. The residents association asked for a design guide for medium density housing years ago but nothing happened and more ugly cheap infill continues to be built. But WCC has coloured in a map so all is good.

Interesting ! Do you really think that the stymying of the schemes is because of the WCC – I had the impression that it was more likely to be because of Stride, the developer, rather than WCC – but I freely admit that I am not that knowledgeable about J Ville

Its here is all its glorious history…..

https://eyeofthefish.org/more-mall-for-jville/

Including this lovely handbrake from the mouth of the council

“Richard MacLean – WCC

Johnsonville Mall application to be notified

….

Wellington City Council asked Mr Hill, an Auckland planning consultant, to make the call on what basis, in terms of the Resource Management Act, the application be considered. This followed controversy earlier this year over the Council’s notification of a proposed District Plan change (Plan Change 66) designed to protect the vibrancy and vitality of central Wellington’s ‘Golden Mile’ against the effects of large-scale retail developments.

Plan Change 66 would include a ‘trigger’ affecting applications for shopping developments larger than 20,000m² gross floor area (GFA) of retail activity. It would require such applications to provide information on what impact the proposed development would have on the economic fortunes of the ‘Golden Mile’. DNZ has stated that consent is sought for a GFA of retail activity of almost 30,000m² – compared to the 8500m² of comparative retail floor space in the existing centre.

Haha to the final comment from Feb 2009 – “likely to be shelved for a year or two”. Should that have been a year or twenty?

How about this one,

Wellington City council.lobbies for government to be given unilateral powers to lift district plan heritage designations along with the Heritage NZ classifications on any building across the city , all dependant on a simple council majority vote….

Oh, did Green and Labour councillors actually mean this as a serious proposal ..

I guess that means their Parliamentary party members will stop saying nasty things about Bishop’s current fast track legislation …. because at least his has a 6 month assessment by a separate panel

It is so hard right now to read the paper, especially those published on April 1st. Everything looks like a giant tongue in cheek farce. I honestly can’t tell whether Luxn is joking when he speaks – it is just cliche after cliche – and then everything that Seymour says is uttered with that curious little half smirk, and Peters!!! Oh boy – politicians – I hate the lot of them. Liars and cheats the whole bunch of them.

The Heritage system has got itself to blame for the mess it is in though, as their blind insistence and refusal to compromise has meant that many fine buildings cannot be restored and are left to rot instead. They need to be able to compromise and be flexible, occasionally.

I would say WCC came to the party too late. It’s probably all a series of unfortunate events. Historically I perceive WCC as being anti-malls as they were seen to have sucked the life out of the CBDs of places like Christchurch. By the time WCC got over the threat to the viability and vitality of the Golden Mile the GFC had come along and the mall owners either got cold feet or couldn’t get financing. Since then there’s been Covid and interest rate rises and latterly suggestions by the owners that only mega tall apartment buildings can make redevelopment viable. And Stride would like someone to pay to double track the train line.

Plan change 66 referred to in the 2008 resource consent decision is what I was trying to remember. See para 212 re the sustainability of the Golden Mile. As I recall the Plan Change was made in response to the proposed J’ville redevelopment although late in the piece WCC ended up supporting the proposal and a resource consent was granted. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/what-government-is-doing/fast-track/Johnsonville-Town-Centre-Redevelopment/076.08_attachment_4_2009_rc_decision.pdf

Perhaps J-Mall could be preserved as an educational centre demonstrating the history New Zealand Town Planning. And lurking within it, a revised National PolyTechnic might find it a good place to plonk a new School of Architecture and Urban Design.

In the meantime, the retail centre of Wellington can continue it’s drift north.

Henry – have you ever actually been inside the J-Mall? I have – and oh boy, it is so bad it barks loudly and wags its tail. I’m unclear who the genius was that designed it in the first place and if it was ever a success story (presumably it was, at least for the first week?) but it really is pretty…. dated. Pretty bad. Pretty vacant, if you’ll excuse a Sex Pistols reference. Nice people, I’m sure, but really it requires dynamite and a rebuild. Actually, it requires more than that – it really does require a complete redesign and rebuild from the ground up. It needs some activation that does not arrive on a car that parks for 5 minutes and then drives on. It really needs a multiple use – nothing that 5000 new flats could not produce. It needs growth – it needs a PROGRESSIVE agenda.

It’s important for students to be as aware of the effect of poor design and bad implementation as they are of good.

J-Mall stands as a city-block-sized example and its educational possibilities should be eagerly grasped for the lessons it provides.

The basic bones of J-Mall’s “dated” design can be traced all the way back to it origins in the late 1960s

https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/21213/johnsonville-mall-1973

it limped on in that form till the early ’90s,

https://www.facebook.com/photosoldwellingtonregion/photos/a.739835352771405/1156751371079799/?type=3

The current decor and styling were added, then, scratch deep enough and its still a 60s mall with a truck load of lipstick….

At least back in the day there was a Farmers and a real fruit and vegetable store. In the early 2000’s we used to do family trip to Wendy’s for an ice cream on Sunday afternoons but alas no more.

I think Stride proposed 18 storey zoning for the district plan for central jville. Got turned down from what I know

New District Plan has 35 metres in centre of J’ville and 21 metres surrounding so 9 storeys surrounded by 6 storeys. From memory both initiated by WCC.

Ahh Jville aka the triangle of death by slow traffic

I remember the TipTop factory, then Big Fresh had the the aisles with animatronic performances by singing veges and cows and whatnot – kids would push the buttons and the godawful cacophony would lumber back into life for the 12th time in half an hour – it’s all on YouTube somewhere

edit- try this

https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/07-04-2017/remembering-big-fresh-new-zealands-greatest-supermarket-of-all-time

North of Raroa train station back when Fraser Ave had the milk depot at the bottom there were animal yards and a drovers road down to the abbatoir at Ngauranga Gorge

It was briefly a BMX track then, it’s now nasty little shoeboxes

I remember down the back road to the quarry at night, teaching a mate of mine how to ride a trailbike, We’d smoke up and listen to the animals in the abbatoir – the pigs knew what was coming..

The way to fix Jville would be an express elevated car lane that is on pillars at the motorway exit with an offramp for Broderick and the main rd through to Khndh, then with the North end it would land on an enlarged roundabout by the police station and feed Ohariu/Glenfield/Newlands

Local traffic to the mall / Fraser Ave/ Motorway South and North could feed underneath the elevated road

One would be basically leaving and one would be arriving – keep the roundabout by KFC for those getting out North and it could have a lane up towards St Johns which could join the new roundabout for locals going to the Paparangi end of Newlands

Elevated roads cost a bit but it would work for that space