Its both hard to write something on Nelson Madela, and also hard not to. But here goes.

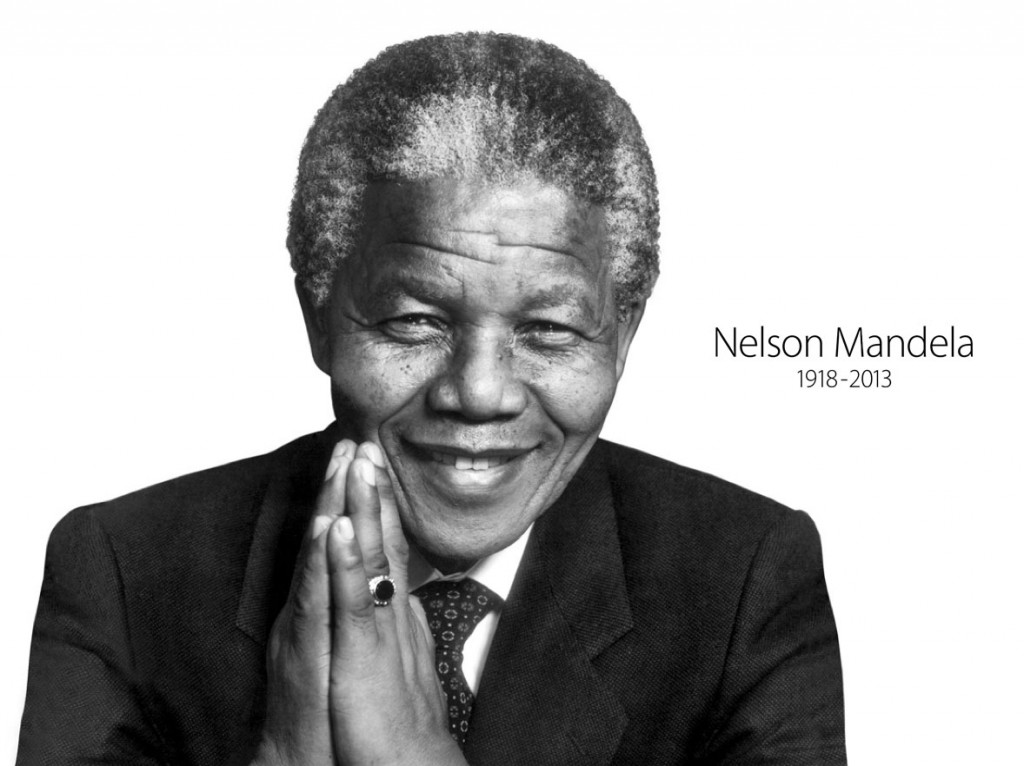

He has little to do with urban life in Wellington, and therefore there is no reason why he should be appearing in this blog, yet, he is quite possibly the most well respected politician of all time. How could I not acknowledge his passing? Pages and pages of writing are appearing, mourning his death, and celebrating his life. Facebook status’s around the world are full of witty comments like “Free, Nelson Mandela”, from people young enough to have never known him. My little cousin, who I think I was babysitting and she was then about 3, at the time Nelson walked free from Robben Island, has proudly written a eulogy to him, and is almost in tears, despite never having met him. I too feel sad that he has gone, although immensely happy that he has been released from life, having been kept in limbo for the last few months or even longer, neither really alive, nor really enjoying a peaceful release.

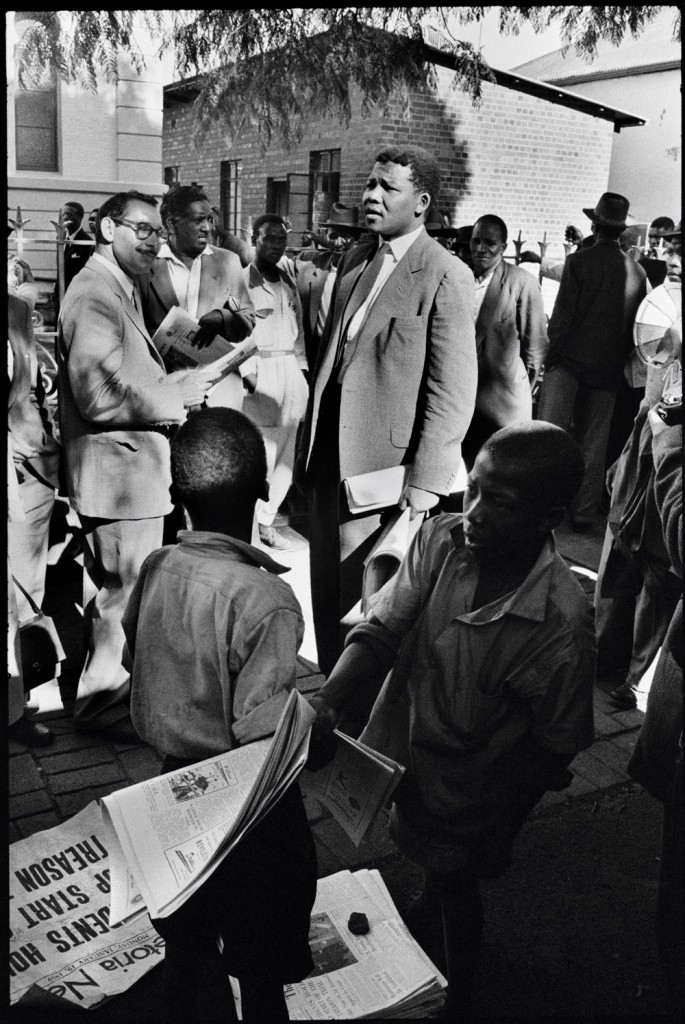

I think that we are all, every one of us, calling him a saint for his extraordinary act of forgiveness. When I was growing up, Mandela was portrayed by the press as this dangerous criminal terrorist, fortunately locked way to protect the whole world from his badness. Yet, he was nothing of the sort. He was a well-educated lawyer, arguing for black people’s rights. No terrorist, not he, not at all. Never. When he went in, he was never expected to survive, and certainly not that he would outlast them all, even his jailers and even his jail, and become President of the most fucked up country in the world – even if there is a lot of competition for that title now. But he walked out of his jail cell – remember the day? – he was in no hurry, he’d been incarcerated for 27 years, and while all the press thought he might be dashing out through the door, glad to get out, poking out his tongue and giving his jailers the fingers, as many who are released must feel, hatred and resentment instilled deep in their heart. And yet, and yet, and yet. The BBC channel I was watching kept the commentary going, waiting for the door to the prison to open, and for this ex-radical to walk out. The rest of the prison was empty – all the other inmates had gone, if I recall correctly. The prison, and the prison staff, existed now only for him. The man who would not say no. Who would not renounce violence, or terrorism. Who would not say I was a Bad Boy and deserved my punishment. We waited. The world waited.

And eventually we twigged what was happening. Mandela was in no hurry to get out, he was still inside, actually going round and thanking his jailers, the men who had been his only companions for the last few years. I think it was at that very stage, before we even got to see that lovely smiling face – that we realised what sort of a man we were dealing with. That is: a man who had the capacity for forgiveness. A man that realized that if he so much as said: Rise Up Black People, and kill your oppressor, then mass bloodshed would ensue. But, luckily for South Africa, and for South Africans, black and white, he did not. He instilled in them the capacity for forgiveness, for truth and reconciliation, factors not well known amongst poor, badly educated men, men who were more akin to seizing a machete and hacking, as we see all too often. Where was the equivalent of Mandela in Rwanda and where is his equivalent now in Central African Republic? South Africa is far from perfect in any way today, and far too much violence stalks the street yet, but so far the lid has been kept on the pot, and violence has not boiled over. Not quite, not yet.

But some will argue, and they may well be right, that one oppressor has just been switched for another. Black switched for white. As it has been in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe, once known as the bread basket of Africa, as it produced so much grain from carefully managed white farms, feeding itself well and exporting masses more to feed the rest of the continent. Now known as the basket case of Africa, where people are starving, where farms have been forcibly removed from whites and given to blacks, and from which no food is produced. A friend of mine from Zimbabwe has just been back there – never again she said, it’s just too bad, too dark, too evil. People will not be singing Mugabe’s praises when he dies, as they are singing the praises of Madiba today. Yet how do you change the very fabric of society, change bloodlines, and careers, and family histories, without spilling blood? The only way is non-violence, very, very carefully. Yet, sometimes you have to fight.

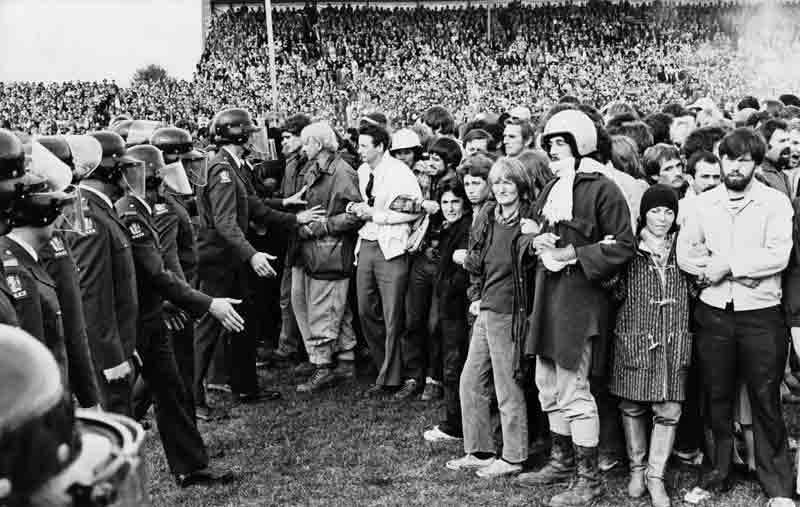

For me, and for many others, the closest we ever got to Mandela was fighting for him, fighting against apartheid, in the battles of the 81 Springbok tour. Amazingly enough, no one was killed, but there were some close calls. Shocking to the police, who called themselves Red Squad, and Blue Squad, the protestors called themselves Biko Squad, after Steve Biko, the South African journalist who was beaten to death. Did we call ourselves Mandela Squad at all? I don’t remember – it was probably too early for the mythologizing to begin, but we certainly sang chanted, heartily, and very much out loud: Freeeeee, Nelson Mandela. And Nelson Mandela watched listened, thousands of miles away in a small concrete prison cell, on a tiny black and white tv radio, watched listened with his jailers as New Zealand split itself in two, and said to the world, No, we will not play with a Racist country. And in our own tiny way, New Zealand helped kill apartheid. Look at the eyes of those people on the field, in a stadium full of rugby-mad rural folk, snarling for rugby at any cost. Some of the bravest protesting this country has ever seen. And yet, nothing like as brave as Nelson Mandela.

Free at last, free at last, good god almighty, free at last.

Thanks for a good life.

Doubt you would have been singing Free Nelson Mandela during the Springbok tour – the record was released in 1984!

Dammit JP, you’ve ruined my story. You’re right of course, I guess, but my memory says the opposite. We sang the words Amandla, and others I can’t remember – it was all quite fun until the fists and batons started flying. Aaah, those were the days.

‘Chant’ is probably the word you are looking for Maximus. They were numerous and succinctly summed up historic and prevailing racial violence and repression – and not just in relation to South Africa.

History is written by the winners. Revisionist history is written by those with a bone to pick.

In Saturday’s newspaper there was an excellent life history / obituary by someone, un-named, but published under the tag line of the Daily Telegraph. It is a pity that we no longer have journalists capable of writing such things ourselves, but it was a mostly well-written and informative piece, even if it was from a staunchly Conservative organ (not in the Colin Craig sense of wackiness, but more the Margaret Thatcher sense of straight-laced ness ). Even so, it ended with a bitchy note – that he was a failure as a CEO to the country. Pity that it had to say that.

And of course an interesting dilemma for the government – which they have decided to ignore, so it is not a dilemma – should any 81 protestors go to Mandela’s funeral?

http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/9493269/Kiwi-Mandela-delegation-without-tour-protesters

For those of you that don’t remember, or weren’t around in those days, virtually every night of the week, on our black and white one channel TV (ok, it may have been a two channel, color TV to others, but honestly, ours was very pro SA: just Black and White. No coloureds), the screen was filled with protestors, including two prominent people: Kevin Hague and John Minto, amongst others. Minto particularly feels the injustice inherent in the world, and so will protest about most things – Hague has gentrified a little, and is now an MP. While Minto undoubtedly meant much much more to Mandela than John Key or David Cunliffe ever will, Hague would seem to be an obvious choice if they want a formal relationship with Government. Certainly more so than Murray McCully, who was a very pro-tour kind of rugby meat head in those days. I hope he is not going…

…and of course Trevor Richards as well, from HART. Even the Dom Post editorial is agreeing with you Max: they point out that the people who are going, although, no mention of McCully, were very Pro-Tour:

“Included in the delegation are two members of the National government that welcomed a racially selected Springbok rugby team to New Zealand – Jim Bolger and Sir Don McKinnon – and a prime minister – John Key – who claims not to recall whether he opposed or supported an event which divided the nation. Excluded from the delegation is anyone who played a prominent role in the protests.

In the ordinary course of events that would be unremarkable. State funerals are staid, formulaic affairs. But Mr Mandela was not an ordinary man and neither are the ties that link New Zealand and South Africa.”

Funny how all those decrepit old has-beens want to go and stand in the glory of Mandela now, but weren’t prepared to stand up for him back then.

Well, I see that Hone Harawira is going – under his own steam too – Good on him ! Although predictably, many of the whingers on Stuff are making comments about how he shouldn’t be going, there is at least one person on there who thinks he should be:

“Groper2012 1 hour ago – Why would Nelson Mandela want a bunch of white guys who exercised their right to watch a ‘game of rugby’ heading to his funeral to posture about? the comments below are hilarious. A bunch of monoculturalists who stare down their noses at their own indigenous people’s struggle in their own country, heading off to celebrate human rights achievements fought for ‘elsewhere’ while pretending the situation they continue to perpetuate in their own backyard doesn’t exist. What a pack of donkeys. Good on you Hone! At least someone is heading over to represent the protesters who had to fight the attitudes of the same donkeys making ignorant remarks in this forum. You’re the same ignorant lot who glued yourselves to TV screens to watch rugby in 1981.”

http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/9497375/Hone-Harawira-heading-to-Mandela-funeral

Don’t know about you, but I stayed up to watch the Mandela memorial service live. Not on TV One, nor TV2, nor TV3, but on the only broadcaster we have left, Al Jazeera. Good coverage – curious service – but a stunningly good speech by Obama. Give that man’s speechwriter a medal! Beautifully put, Barack.

Indeed, Obama’s speech was great. Pity that we don’t have politicians of his calibre in NZ. I find it interesting though, that we have not seen or heard any of the other world leaders speeches. There was to be one from India, and one from China, and possibly even one from Cuba? All coming after Obama’s speech. But I haven’t seen any reports of anyone else except for Obama. Dd the other speakers decide to just give up and go away?

And so we reach the end of the week after the death of Mandela, and the world is an even stranger place. A sign-language translator who clearly does not know how to translate into sign, who claims that he was visited by angels and had to keep saying the same thing so that he did not break out into violence…. Him standing there while Obama made his speech, secret servicemen bristling everywhere, except none had checked out the signing translator… The irony and sadness of Mandela preaching a lifetime of truth and forgiveness and humility and love and honesty, and NZ being represented by John Key who exemplifies none of those attributes and claims not to even remember if he was pro-tour or not, meanwhile back in NZ we have a State Services Commission report into the leaking of a document, and they spend half a million, and find out nothing, and no one is to blame, and of course nothing ever happened, except it obviously did, and there’s not much truth or reconciliation going on there.