Today I’m taking a different tack to the Eye of the Fish. I’m going for a walk down a shopping street, in the spirit of some retail therapy. My TV blew up last night – the sound still goes, but the picture doesn’t – and what is the use of a TV without a picture? Radio without Pictures? And in this modern age, do I need a TV at all? Or rather – I need a screen, but broadcast TV, with all its advertising – for what earthly reason would I want that ghastly experience back, what with the non-stop adverts for Harvey Fucking Norman? And yet, sadly, it is to HFN that I must go, as they have the widest range of screens.

But there are other ways to shop, and perusing the vast interwebbings of our modern life, I found myself, I know not how, at a text of “The Arcades Project”. German Jewish writer Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) began this to chronicle the shopping experience of Paris, collecting snippets from other works. Let us walk on…

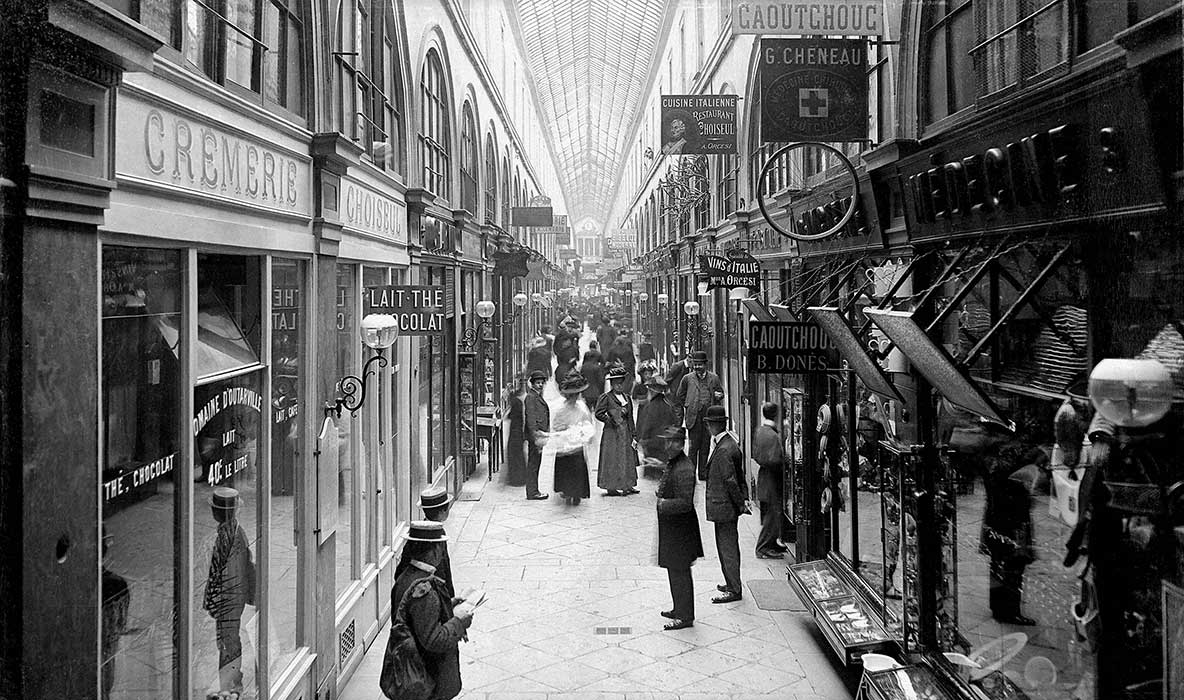

The physiognomy of the arcade emerges with Baudelaire in a sentence at the beginning of “Le Joueur genereux”: “It seemed to me odd that I could have passed this enchanting haunt so often without suspecting that here was the entrance.” <Baudelaire, Oeuvres, ed. Y.-G. LeDantec (Paris, 1931),> vol. 1, p. 456.”

Specifics of the department store: the customers perceive themselves as a mass; they are confronted with an assortment of goods; they take in all the floors at a glance; they pay fixed prices; they can make exchanges.

“In those parts of the city where the theaters and public walks . . . are located, where therefore the majority of foreigners live and wander, there is hardly a building without a shop. It takes only a minute, only a step, for the forces of attraction to gather; a minute later, a step further on, and the passerby is standing before a different shop. . . . One’s attention is spirited away as though by violence, and one has no choice but to stand there and remain looking up until it returns. The name of the shopkeeper, the name of his merchandise, inscribed a dozen times on placards that hang on the doors and above the windows, beckon from all sides; the exterior of the archway resembles the exercise book of a schoolboy who writes the few words of a paradigm over and over.

Fabrics are not laid out in samples but are hung before door and window in completely unrolled bolts. Often they are attached high up on the third story and reach down in sundry folds all the way to the pavement. The shoemaker has painted different-colored shoes, ranged in rows like battalions, across the entire facade of his building. The sign for the locksmiths is a six-foot-high gold-plated key; the giant gates of heaven could require no larger. On the hosiers’ shops are painted white stockings four yards high, and they will startle you in the dark when they loom like ghosts. . . . But foot and eye are arrested in a nobler and more charming fashion by the paintings displayed before many storefronts. . . . These paintings are, not infrequently, true works of art, and if they were to hang in the Louvre, they would inspire in connoisseurs at least pleasure if not admiration. . . . The shop of a wigmaker is adorned with a picture that, to be sure, is poorly executed but distinguished by an amusing conception. Crown Prince Absalom hangs by his hair from a tree and is pierced by the lance of an enemy. Underneath runs the verse: ‘Here you see Absalom in his hopes quite debunked, / Had he worn a peruke, he’d not be defunct.’ Another . . . picture, representing a village maiden as she kneels to receive a garland of roses — token of her virtue — from the hands of a chevalier, ornaments the door of a milliner’s shop.” Ludwig Borne, Schilderungen *us Paris (1822 und 1823), ch. 6 (“Die Laden” <Shops>), in Gesmmmelte Schriften (Hamburg and Frankfurt am Main, 1862), vol. 3, pp. 46-49.

On Baudelaire’s “religious intoxication of great cities” the department stores are temples consecrated to this intoxication.

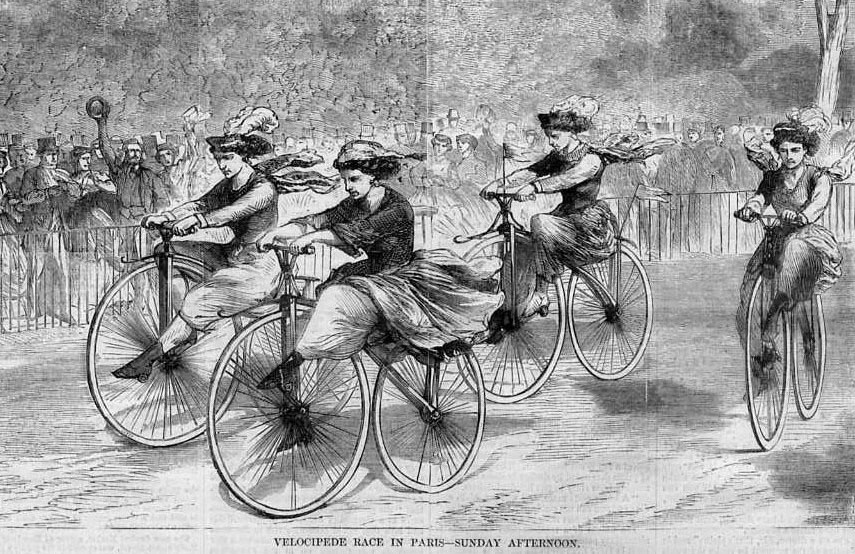

….he writes on, touching on bicycling and fashion…

F. Th. Vischer on the men’s fashion of wide sleeves that fall below the wrist: “What we have here are no longer arms but the rudiments of wings, stumps of penguin wings, fish fins. The movement of these shapeless appendages resembles the ges- ticulations — the sliding, jerking, paddling — of a fool or simpleton.” Vischer, “Vernunftige Gedanken iiber die jetzige Mode,” p. 111.

Important political critique of fashion from the standpoint of the bourgeois: “When the author of these reasonable opinions first saw, boarding a train, a young man wearing the newest style of shirt collar, he honestly thought that he was looking at a priest; for this white band encircles the neck at the same height as the well-known collar of the Catholic cleric, and moreover the long smock was black. On recognizing a layman in the very latest fashion, he immediately under- stood all that this shirt collar signifies: ‘O, for us everything, everything is one — concordats included! And why not? Should we clamor for enlightenment like noble youths? Is not hierarchy more distinguished than the leveling effected by a shallow spiritual liberation, which in the end always aims at disturbing the pleas- ure of refined people?’ — It may be added that this collar, in tracing a neat little line around the neck, gives its wearer the agreeable air of someone freshly be-headed, which accords so well with the character of the blase.” To this is joined the violent reaction against purple. Vischer, “Vemirnftige Gedanken iiber die jetzige Mode,” p. 1 12.

On the reaction of 1850-1860: “To show one’s colors is considered ridiculous; to he strict is looked on as childish. In such a situation, how could dress not become equally colorless, flabby, and, at the same time, narrow?” Vischer, p. 117. He thus brings the crinoline into relation with that fortified “imperialism which spreads out and puffs up exactly like its image here, and which, as the last and strongest expression of the reflux of all the tendencies of the year 1848, settles its dominion like a hoop skirt over all aspects, good and had, justified and unjustified, of the revolution” (p. 119).

“Similarity of the arcades to the indoor arenas in which one learned to ride a bicycle. In these halls the figure of the woman assumed its most seductive aspect: as cyclist. That is how she appears on contemporary posters. Cheret the painter of this feminine pulchritude. The costume of the cyclist, as an early and unconscious prefiguration of sportswear, corresponds to the dream prototypes that, a little before or a little later, are at work in the factory or the automobile. Just as the first factory buildings cling to the traditional form of the residential dwelling, and just as the first automobile chassis imitate carriages, so in the clothing of the cyclist the sporting expression still wrestles with the inherited pattern of elegance, and the fruit of this struggle is the grim sadistic touch which made this ideal image of elegance so incomparably provocative to the male world in those days.” Dream Houses.

“In these years [around 1880], not only Joes the Renaissance fashion begin to do mischief, but on the other side a new interest in sports — above all, in equestrian sports — arises among women, and together these two tendencies exert an influence on fashion from quite different directions. The attempt to reconcile these sentiments dividing the female soul yields results that, in the years 1882-1885, are original if not always beautiful. To improve matters, dress designers simplify and take in the waist as much as possible, while allowing the skirt an amplitude all the more rococo.” 70 Jahre deutsche Mode (1925), pp. 84-87.

“Here fashion has opened the business of dialectical exchange between woman and ware — between carnal pleasure and the corpse. The clerk, death, tall and loutish, measures the century by the yard, serves as mannequin himself to save costs, and manages single-handedly the liquidation that in French is called revolution. For fashion was never anything other than the parody of the motley cadaver, provocation of death through the woman, and bitter colloquy with decay whispered between shrill bursts of mechanical laughter. That is fashion. And that is why she changes so quickly; she titillates death and is already something differ- ent, something new, as he casts about to crush her. For a hundred years she holds her own against him. Now, finally, she is on the point of quitting the field. But he erects on the banks of a new Lethe, which rolls its asphalt stream through arcades, the armature of the whores as a battle memorial.”

Just a FYI in case you are interested. I woke up at 4am this morning and couldn’t get back to sleep, hence I started this post. I’ve just finished it at 8.30am – so about 4.5 hours, including trawling through the webs for suitable images – getting lost trying to find a picture of a cyclist in a crinoline skirt, or some better period shots of Boulangerie and Charcuterie and Patisserie – its hard to find the right image.

I visited Prague in the 1990s – relatively soon after the Velvet Revolution. The 18th and 19th Century parts of the city were filled with residential and commercial buildings wrapped around courtyards. All the street frontages and many of the courtyard frontages were lined with elegant shops at ground floor level – quite a few as intricately ornamented as your Paris examples. While signs of post-communist commerce were starting to show (let’s not talk about McDonalds in Wenceslas Square) many of the shops were empty.

It was strange to think of life in the city – so obviously built on the bourgeois delight in retail – as it must have been for the preceding 50 years. Did the residents carry on shopping even when consumer goods were rationed or almost non-existent? Did they stoically sell and buy potatoes and acrylic shoes in those gilded bijouteries?

I too went to Prague – just a mere week after the Velvet Revolution – it was fascinating. Wenceslas Square still had a large circle of wax from the multitude of candles lit during their vigil. People were gathering in the old town square near the clock tower, as there was no newspaper they could trust – Pravda was still available but no one was buying. Voice only, face-to-face meetings were the only way of gaining truthful information.

As you say, it was still a soviet satellite and so there was no capitalist commerce at all in that first week. I still remember seeing a shop with just three jars of jam for sale in the window – now this would be a great hipster staging point with a post-ironical neo-canonical viewpoint, but in those days there literally was nothing to eat – their supply lines from Russia had stopped and new supplies from the West had not yet materialised. I too went hungry – there were no restaurants that I could find apart from the one up near the Railway station, a grand old place. No one spoke English – only Czech or Russian, neither of which this small Fish could speak – my schoolboy French and night class German trying to make up the gap to no avail. Perusing the menu at the Railway Station restaurant, all in Czech, the only word i could find was biftek, which I took to be a derivation of the German word beefsteak, so I had that. I don’t think there was a language guidebook available at the time – Lonely Planet had not yet got a Czech version. I could find no bookshops: certainly no written info in English.

There was no hotel or hostel i could find, so i managed to blag a bed in the Tesla football club overnight, out of the freezing cold. There were two other people staying there, both Russian gymnasts with bulging muscles, neither of whom could speak a word of English. Nor could I speak a jot of Russian. We had a brief political discussion: me saying: “Boris Yeltsin, da?” Their reply was a very firm “Nyet”. A pause, then they asked: “Margaret Thatcher, da?” My reply was also “Nyet….” Conversation closed. To bed and a very deep sleep.

Years later I went back to Prague, to find to my dismay that there were now no less than four McDonalds burger bars in the main street alone, and brochures on every street for concerts of Vivaldi by talented violinists. Porn was everywhere, those beautiful Czech girls now whoring their bodies in an effort to get food and work. Everyone spoke English and German, no one spoke Russian any more. Bookstores on many corners, all in English. What I found most notable was that the city had erupted into colour: capitalism uses red, green, blue, purple, rather than the grey and brown of the Soviets.