Prince Rogers Nelson, androgynous funkster, talented musician, sexy motherfucka, and the soundtrack to my life, has died, aged only 57. We all thought it was bad enough to have Bowie and Rickman pass away so early at 67, just a month or two back, but for Prince to pass on to the afterlife a whole decade earlier than that, is just a truly tragic shame.

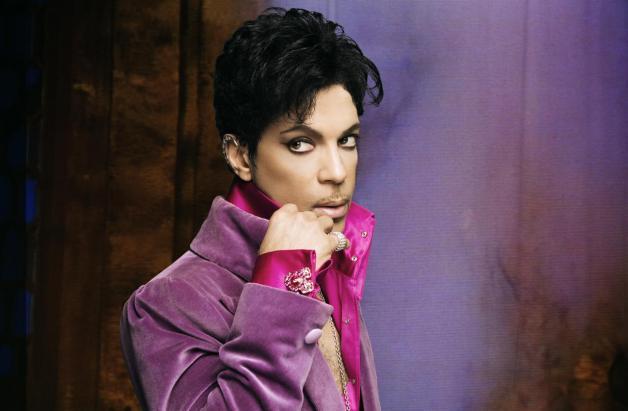

He was a prolifically talented man, obsessed with music and seemingly obsessed with sex, although arguably to him these two things were totally entwined. Prince was Sex on legs, in male form, but perfectly happy to be in touch with his feminine side too. He was tiny, and yet a ball of energy that could put even Mick Jagger to shame. A wispy moustache curled snarling on his upper lip, a guitar permanently in his hands, lace ruffs at his collar and luxuriously improbable materials to his every outfit, Prince (to me) represented the 80s and the 90s down to a T.

Back in the 80s, our Park Road flat danced, impromptu, to Prince, who graced the living room in the form of a cardboard poster of Prince astride a purple motorbike, courtesy of some late night boosting from a movie theatre screening Purple Rain. Prince WAS the 80s – bursting onto the scene in a prodigious manner during Karen Hay’s Radio With Pictures, and wowing the world with his first album, where he apparently played every instrument on every track, as well as singing deep low bellows and perfectly falsetto high notes all in the same line. He confused the heck out of bogans who preferred their music to be sung in black t-shirts by men who screamed a lot, and frightened their sexuality by straddling the music of black and white, of girls and boys, and of sexpots and virgins. Prince lured them all.

Prince was also my soundtrack to the 90s. I was lucky enough to see Prince sing live 4 times, all in London. Not for me the recent Auckland concert, where he sang alone? on stage, which sounds intimate, but probably wasn’t. No, I endured the stadium rocking of Wembley, with all its bad cacophony of sound, the spaciousness of Earls Court, luxurious by comparison, and sadly missed out on the 42 nights he played in succession at the O2 – the Dome. But every night, each time he played a gig, he would also play an after party, where he would come to a local club, about midnight, and play on till about 3am. One time, I got handed a flier to his after party gig, which was playing just down the street from me – but ignored it, thinking it was a hoax. It wasn’t – but 200 lucky people had an audience with Prince that night. Then he would go back to the hotel and play some more.

Paisley Park, his recording studio in Minneapolis, holds his secrets, which I am sure we will see come out one day, and flood the world with what is surely a massive back catalogue of further tunes. I only own 13 Prince albums. I’m sure there will be more now, on the pipeline. Prince will live on, in music, in a way that architects can only dream of in their buildings.

Sometimes it snows in April…

Sad day indeed.

best fb comment from a friend: i think ‘when doves cry’ is my all time favorite song. it was my teenage lament. i was a miserable bastard, filled with the ongoing emotional side effects of regection, longing and unrequited love/lust :((((((((

from the New Yorker today:

This morning, the news came that paramedics were responding to a “fatality†at Paisley Park, the sprawling, modern studio and fairyland in Chanhassen, Minnesota, built by Prince Rogers Nelson as a monument to both his legacy and his eccentric personality. The name that followed was chilling for Prince’s world-spanning collection of fans. The musician was dead at fifty-seven. Last Friday, reports described Prince being ill and forcing his private jet to make an emergency landing in Illinois following a concert in Atlanta; he appeared at a dance party the next day to reassure the public that he was healthy. The enigma proved confounding even in his final scenes.

Prince’s run of stardom during the mid-eighties spawned several hits, films, commercials, collaborations, and what seemed like a limitless trove of recordings. And he’d risen again in the public eye in recent years: in 2014, Prince released “Art Official Age,†and he followed that in 2015 with a pair of albums, “Hit n Run Phase One†and “Hit n Run Phase Two,†which stepped warmly into the soft-thump funk, inventive, borderless jazz, and rallying sentiments that have been taken up by pockets of younger R. & B. acts. He took to singers like Janelle Monáe, Esperanza Spalding, and Lianne La Havas as muses, as well as touring regularly with his band 3rd Eye Girl, and would routinely summon local Minnesota artists to his estate. Presenting at last year’s Grammy Awards, he offered, “Like books and black lives, albums still matter,†denouncing the digital and bureaucratic oligarchies that he’d spoken out against throughout his career.

Fans grew accustomed to an adult version of the Prince they’d seen so mythically in his youth: less a deified king lording over his dominion and more an aged doyen, insulated from the rules and norms of common society but still watching transfixed from his wing, poking at the center at will: a master still at play. “When you’re twenty years old, you’re looking for the ledge,†Prince told Arsenio Hall in 2014. “You want to see how far you can push everything . . . and then you make changes. There’s a lot of things I don’t do now that I did thirty years ago. And then there’s some things I still do.â€

Now we begin the collective, active experience of remembering Prince. New corners of his cavernous catalogue and stories of impressions from those that met him will be unearthed, shared. His is one of the handful of pop legacies whose broadness cannot be simplified in even its most romantic, famous moments, and now we must work to enjoy and adore that legacy as it warrants.

—Matthew Trammell

“Here I go again, falling in love all over,†Prince squeals at the beginning of “Pink Cashmere,†a one-off, gloriously careening six-minute rhythm-and-blues jam he recorded in 1988, at his own Paisley Park studios, for his girlfriend at the time, the British model and actress Anna Garcia (or Anna Fantastic, to crib Prince’s gilded, glamorizing parlance). The song’s opening lyric is preceded by an ecstatic “Oooh!†that contains, as far as I can tell, everything there is to know about the deeply hysterical moment in which a person suddenly recognizes that—oh, God—he or she is really done for. Maybe you were doing all right yesterday—maybe you had yourself together—but now? Someone’s got you fully in his or her grip.

When love hits like that, it can feel brutal, violent, like getting grabbed from behind on a street corner. Then, on the other side of that terror: bliss, wonder. Something like happiness.

This, of course, is merely the situation of being alive, Prince suggests; glory and anguish are always present in everything, and often in equal parts. The paradox of love—how it’s both the kindest and the cruelest thing a person can inflict on someone else—exists in almost all of Prince’s songs, animating them. “The cycle never ends, you pray you don’t get burned, OW!†is how he figures it on “Pink Cashmere.â€

Although the song didn’t make it onto a proper LP until 1993, when it was included on the “The Hits/The B-Sides†boxed set, I’ve long thought “Pink Cashmere†is one of the most intoxicating and almost inexplicably multitudinous rhythm-and-blues songs ever recorded. Prince, like all our best singers, had a cornucopia of voices awaiting deployment, each communicating a separate but essential emotional state. On “Pink Cashmere†he exhibits a staggering range, from a nearly feral-sounding falsetto to a deeper, more guttural alto. It is hard to accept, sometimes, that they were all born from the same body.

The title refers to an actual garment, a gift: a pink cashmere coat, with a contrasting black mink collar and cuffs. Prince had it made for Anna by his personal tailor. Her name was embroidered on the sleeve; an “89†was festooned on the back. I have never seen a photograph of it, but I imagine it to be a kind of bespoke masterwork, a literal manifestation of love’s strange, supple, mollifying embrace. I am certain that she looked incredible with it curled around her shoulders. I am certain almost anybody would.

—Amanda Petrusich

At two-thirty this afternoon, about eighty people were standing outside First Avenue, the club in Minneapolis that figures in “Purple Rain.†Outside the club is a wall with stars painted on it. Embedded in the stars are the names of various acts. Beneath the one for Prince was a collection of those bouquets that florists make with flowers and paper and cellophane and ribbon. Several held purple tulips. Beside the flowers someone had leaned a black Fender guitar. Men and women came around the corner in twos and threes, as if summoned, many having walked from their offices and wearing their ID tags around their necks. In the morning there had been rain, but the sky had cleared and the sun was out.

“Fifty-seven, he’s younger than my mom,†a tall young man with a corona of black hair said. His name was Tom Steffis, and he worked at the University of Minnesota, he said. He stood between Ryan Thompson, a student at the university who was in class when he heard, and Merv Moorhead, who said, “I was working at my computer when I heard, and I knew I had to come down.â€

“He means a lot to the city, because he never really left,†Steffis said. “Minneapolis is small enough that everybody has a story about him.†The three of them shared several, mainly revolving around surprising gestures or acts of kindness.

Then one of them said, “My best friend’s mom in high school was in the opening shot of ‘Purple Rain.’ She waited three hours for the club to open.â€

“Little-known fact,†Thompson said. “The movie wasn’t filmed in here. Everybody thinks it was.â€

“It was the first place he played the song,†Steffis said.

Thompson has blond hair and a beard. He held a fancy-looking camera. “I worked on one of his videos,†he said. “It was seventeen-hour days, and he came out in these glory heels and from the back I thought it was an attractive woman, and he turned around, and I’m like, That’s Prince.â€

“He really came out of his shell these last five years,†Steffis said, and they all nodded. He said that Prince gave parties at his estate, Paisley Park. “It’s this really unique place that’s by the side of the road in the middle of nowhere,†Thompson said.

Steffis said that Prince charged fifty dollars at the door, and sometimes he played. “There was never a guarantee he would play,†Steffis said.

“Sometimes he’d play two or three songs with the band, and he wouldn’t feel it, and he’d quit. Then he’d come back later and play for two or three hours,†Thompson said.

“First time I saw him he came on at four-thirty in the morning,†one of them said.“It was all spontaneous.â€

“That would discourage people from turning out.â€

“They didn’t want to drive out there, and pay fifty bucks and have him not play, I guess.â€

“There was no alcohol, and if they saw you using a cell phone they’d throw you out.â€

“One time he served pancakes at five in the morning.â€

Beside the three young men stood a woman with tears on her cheeks. A number of people held phones toward the flowers and the wall. A reporter and a cameraman from a Minneapolis station threaded their way among them. Hardly anyone spoke.

“My first Prince memory is a couple of my friends and I stayed up all night and when it came to sunrise we ran into Lake Minnetonka,†Steffis said finally.

“That’s the line in ‘Purple Rain,’ †Thompson said, and then all three of them said, “Purify yourselves in the waters of Lake Minnetonka.†Then they said maybe that wasn’t exactly the line, but it was pretty close.

After a moment, Thompson said, “A lady at the coffee shop told me that he used to have forty-hour Tantric-sex sessions back in the day.†“There are so many rumors about him,†Steffis said. They agreed that this was the case, and then the three of them fell silent, too.

—Alec Wilkinson

There will be longer pieces written, and better ones, about the death of Prince, but the main point is that there will be many, and each will demonstrate purely and powerfully how deeply he connected with those of us who loved his music, his spirit, his playfulness, his petulance, his bravery, his youth, his wisdom, his weirdness, his virtuosity, and his vision.

Other articles will go through it all: his family, his father, 94 East, First Avenue, “Dirty Mind,†“Purple Rain,†the coughing on the extended “Raspberry Beret,†every second of every Sign O the Times show, the rest. I’m just making lists here to keep from sinking, just thinking to keep from feeling. “1999†was about the apocalypse, back in 1982. When the real 1999 came, people looked back seventeen years and laughed that nothing had ended. Seventeen years later, we’re all wrong.

We all discovered Prince at different times, but with the same sense—that he had discovered us. Tell your own stories about when you heard a song on the radio, or on a cassette, and how it lit you up from inside. The stories will be surprisingly similar.

Writing to mourn Prince doesn’t seem to make sense. Dreiser said, “Words are but vague shadows of the volumes we mean.†Prince said, “I’m not a woman / I’m not a man / I am something that you’ll never understand.†But we understood at least that. The lyric is from “I Would Die 4 U,†of course. Messianism turns to memorial.

Everyone will carry at least one song with him today. I’m carrying “Still Would Stand All Time,†the gospel ballad from “Graffiti Bridge.â€

—Ben Greenman http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/remembering-prince

and from the Guardian:

Prince: how his androgynous style influenced fashion

From his dancing curls to his high-stacked heels, the legend influenced Versace, Justin Bieber and Matthew Williamson.

In the late 70s and throughout the 80s, the yearly advent of a new Prince album brought with it a visual image as strong and defining as the music contained within. “I wear what I want because I don’t really like clothes,†he lied once, in a rare interview. Like David Bowie, Prince toyed with the ideas of the “otherâ€: the feminine, the alien, the raceless. Through costume and artwork, he created the Prince that became iconic: the wistful flâneur with Egyptian-style eyeliner.

Part Pierrot, part Little Richard and part doe-eyed Bambi. Taken in isolation, each element of his style was one thing, but combined with the music, they spun a web of mystery, a crescendo of coded whispers about gender, sexuality and visual identity. In 2016 – when the most talked-about label in fashion, Vetements, is a gender-neutral one and where the likes of Gucci and Tom Ford have combined men and women’s shows – Prince’s “grey area†style was pioneering.

It all began in 1979 on the cover of his second album. Here the fledgling Prince appeared shirtless, a halo of Farrah Fawcett waves. On the back of the LP, his intentions to kick against rock and soul conventions were clear: there he was, sans clothes, riding atop a winged white horse: a Dionysian nymph full of sexual intent.

But that was a subtle, soft-focus opening shot compared to what was to come. 1980’s Dirty Mind remained his most extreme look (until, of course, the backless pants); a Mac, bikini briefs and a neckerchief. The sexually open content of the lyrics was mirrored by his look, which riffed on the teddy boy revival but added the spectre of the flasher in the local park. On stage, he would augment the look with thigh-high stockings, a fact not appreciated by Rolling Stones fans who booed him off stage when he opened for the band on tour. By 1984’s Purple Rain (and under the guidance of costume designer Marie France), he had perfected his iconic look: frilly shirts that were the cousin of Princess Di’s pie-crust shirts, stack-heeled platform boots and his hair tightly wound into a rapturous bouffant of dancing curls. It was dandyish but it also nodded to the military jackets of Jimi Hendrix and the psychedelia of Sgt Pepper.

This European romantic look cut through his band, the Revolution, but also his associates, such as Sheila E and the Family. Musically, he was generous with his talent and his proteges were many. He liked doubles, multiples of himself and these proteges sartorially mirrored his stylistic changes: silk camisoles for Vanity 6, zoot suits for the Time. On his 1988 Lovesexy tour, his polka-dot suits were colour matched by the complementary bodycon outfits of dancer Cat and Sheila E, which were proto-Henry Holland.

As one of the biggest pop stars in the world, Prince brought a new conversation about gender to fashion. He wore high heels and lace gloves, making the world think about how a man or a woman should dress, pushing the boundaries of taste and acceptability. As singer Frank Ocean highlighted in his tribute: “He made me feel comfortable with how I identify sexually simply by his display of freedom from and irreverence for the archaic idea of gender conformity.†A noted influence on Donetella Versace, Tommy Hilfiger and Matthew Williamson, Prince also directly and indirectly influenced the look of Blood Orange’s Dec Hynes, D’Angelo and Justin Bieber. Prince ignited the conversation about gender that we are still having today.