It is always a slow start to the year, after some quality time spent at the beach. The malaise of having to go back to work hangs heavy over us all, especially as the weather is (normally!) better once you have returned to work after a summer holiday. This year, reasonable amounts of fairly mediocre weather meant more time spent indoors reading, than the more traditional outdoor swimming, sunbathing, and generally fooling around in the waves. Instead, quality time was had by Levi being laid up horizontal, sharing the delights of the recliner with a good book or two. One of these especially caught my fancy – the latest volume by Douglas Lloyd Jenkins, Aotearoa’s very own design scribe. “Beach Life – A celebration of kiwi beach culture†is his latest book, and it is perhaps a curious topic for DLJ as he does not seem to be particularly beach oriented, although having spent the last few years as Director of the Hawkes Bay Art Gallery and Museum, he certainly must have had his beach interest aroused, as the Museum is just across the street from the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean in Napier.

Whether he is a natural born beach lover or not, the end result is captivating, and superbly positioned for summer reading at the beach. It certainly went down a treat with me, and with the other assorted members of the extended family that congregate for Christmas. The book is vaguely chronological, being broken down into three main epochs he notes as:

The Sunseekers 1925-1945

The Sunbathers 1945-1975

The Sunburnt 1975-2005

Being the delicate young age that I am, I fall firmly into just one realm: that of the Sunburnt. Therefore the tales within the other two epochs are delightfully new to me.

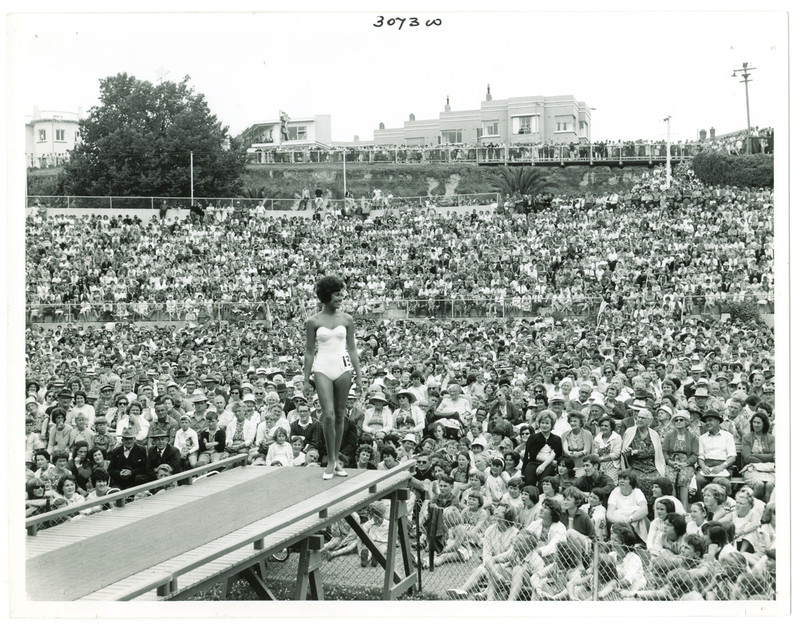

Each of these main areas is then further subdivided up further divided up into sub chapters of Beach Boys, Beach Style, Beach Stories, Beach Mammals etc and eventually Beach Suburbs and Beach Houses. This allows Lloyd Jenkins to explore lots of interesting little facets of the subject in no particular order, in the manner of picking up small bits of flotsam and jetsam off the beach and examining them at leisure. There is a fascinating amount of info within the covers, and a wide range of images, many of them of boys with tight pants and thrusting crotches, and some of girls in barely restrained bikini-clad bosums, but on the whole, the nakedness quotient is kept at a reasonably decorous level. It is the photos of the life-guards performing an Aryan (fascist) salute that opened my eyes, as well as the picture of the 10,000 strong crowd at the Miss Caroline Bay Contest, with legions of elderly matrons looking at the young swimsuit-clad girls on display. Looking on disapprovingly perhaps, or do they all just suffer from resting bitch face? How things have changed: this year the Miss Caroline Bay Contest had only two entries, heralding the end of the free floor show. Not only are the young too unwilling to enter it, even the audience can’t be bothered any more.

Pictures aside, the text is fantastic. Not too wordy, not at all dry and academic, Lloyd-Jenkins’s writing is a joy to read, especially if you can recall his quiet, slightly lisping way of speaking that he demonstrated on TV a decade ago. There is a very dry sardonic wit at work here at times, and the small mini chapters are perfect for a mind to read when addled by a spot too much wine or sunshine. Yet they are short, to the point, and make a whole lot of sense. Let me quote you an example, form the very start of the book, in the introduction:

“In Aotearoa New Zealand the beach is inescapable. Life at the beach is simply part of belonging to an island nation. There is no point in the country’s interior that is so distant from the coast that it cannot be reached for a trip to the beach. In a sense, New Zealand is a ring of coastal beaches within which the nation is contained. Kiwis have therefore come to see the beach not so much as the geographical fringe but as defining the perimeter of their culture. New Zealand starts and ends at the beach.†p9

That makes a lot of sense to me, and also helps define our differences from the British. They experience their island differently from ours. While there are some parts of the British Isles that are still wild and craggy (think Poldark’s rides along the Cornish coastline), much of the accessible beach land is hideously ruined with caravan parks, fiddly twee changing sheds, industrial wastelands and the like, but there is no tradition of bach dwelling. Instead, their sea side retreats were built in the days when the sea wind was to be feared and avoided, and small dwellings huddle in valleys with their backs firmly against the sea. But then again, there are not many parts of Britain where the temperature is amenable to stripping down and racing into the briny at the first opportunity, as we tend to do here. To a Kiwi, the Poms just don’t seem to get what it means to go to the beach. Get in, get naked, get wet! Have a good time! New Zealand really does start and end at the beach.

New Zealand is of course also heading the way of seaside decrepitude, albeit at a much slower rate: there is no doubt to my mind that the hideousness of many modern beach houses has forever ruined some formerly beautiful retreats. The worst one that springs to mind is the line up of ghastliness on the edge of the Able Tasman Park, where Kaiteriteri has been ravaged and left for dead by people intent on hitting everything with the Ugly stick. Some people clearly do not subscribe to the dictum that beach living should be fundamentally different to city/suburban living, and their crass and ugly houses show this off all too well. Cheek by jowl siting does not help of course, and the brilliance of the natural surroundings in Abel Tasman only show off how awful the architecture is that surrounds it.

There is a reason that houses by brilliant architects like Ken Crossan, or Lance and Nicola Herbst, capture the eye of the nation with their designs for informal, beach-side living in a manner that is so fundamentally different from that of the city. We’re certainly judgemental enough. Is this just me, or is this a trait common to more of us? Lloyd Jenkins again, right near the end, puts it this way:

“Anyone who owns a beach property, old or new, will have had the experience of looking out the window to find two or more people initially looking, eventually pointing, engaging in what is clearly an intense conversation about their house. During summer holidays at the beach, local architecture was more inclined to come up as a topic of conversation than in town, where few people had a mutual architectural reference point solid enough to sustain conversation.

Generally speaking, the New Zealand public came to judge any beach construction using a simple rule: does it fit in or does it stand out? It was a crude measure broadly applied, but Kiwis would prove considerably more sympathetic to a beach house that they considered merged with the environment than one they considered to be an addition to it. Of particular sensitivity was the setting of a house close to the beach boundary or in any raised position that was perceived to dominate in a way that implied private ownership of a public beach.†p273

I absolutely loved this book and if I have one criticism, it is just that for me, I would have liked to have seen and read more about beach architecture, but the book is so much more than a discussion about the merits of the bach. It touches on nudity and prudity (too much of the second and not enough of the first), the good points (or not) of woollen togs vs nylon, the hours of bathing in the Victorian era and the beginnings of surfing in the Kiwi surf beach culture. My one regret – that I did not have the gumption (or, perhaps, the ability) to write this book myself. Well done Mr Lloyd Jenkins.

On a completely different manner, and just because I think that the Architectural community should know, a post has appeared on the Wellingtonista website that should be an absolute boon to all house designers in Wellington. Tom Beard (from the formerly brilliant WellUrban website, and sadly, not from this website) has produced a plan / map of where the wind zones are in Wellington, in a graphic format that is much more user friendly than the official one produced by WCC. Go Tom!

Anyway – here’s a link: http://wellingtonista.com/2017/01/18/wild-wind-blows/

That B&W title image for this post on the homepage tho (also third image in this thread)- what beautiful lines and those stacks…

I’m of course talking about the moderne delight on the crest of the hill behind the scene of the ‘action’. Off to GMaps to see if it’s still there.

Btw – that geezer to the right of the ‘elderly matrons’ spent a considerable sum at the chiropractor’s clinic in the following months.

Indeed it is still there – Caroline Courts: https://goo.gl/maps/6zX33af6szu

Looks better in the original context though. Interesting set of flats – anyone know anything about them?

Caroline Courts apartments were designed in 1937 by architect Charles Lamb, who billed himself as “Formerly of London and New York”. Wikipedia lists a London architect Charles Lamb but as he died in 1834, it’s not him. There is another Charles Lamb in America, but he also died too early for this. And apparently 2 days ago, in Taranaki, a Mr Charles Lamb passed away in a rest home… The search continues….

Further to that: the London Architect Charles Lamb sounds as though he had a good appetite and a good sense of humour – there is a book: “A Dissertation Upon Roast Pig and Other Essays” by Lamb, Charles, 1775-1834

Not your Charles Lamb, but a good little piggy trail none the less….

…but his trail has gone cold. The Silence of the Lambs, so to speak…

Ewe should stop with the terrible puns now: http://www.kappit.com/img/pics/201310_1611_dihce_sm.jpg

Its got me intrigued though. How can there be an article about Charles Lamb designing some Art Deco apartments in Timaru, and then no info anywhere else on the web about him designing anything else? It’s like he vanished into thin air. Surely he designed more than one building in his career? Surely someone somewhere has a record of him?

Ask Jessica Halliday – she’ll know.

Weighing in from Christchurch thanks to Guy’s persistence…

I don’t know of a Charles Lamb. There was a Colin Chisholm Lamb in Christchurch who was active in this period. Perhaps Mr David McBride of the Timaru Herald got his first name wrong, leviathan?

My sparse notes on Colin Lamb do note “London offices, 1930-35” – so a chance this could be him. I’ll see if I can remember to look him (or Charles) up in the Art History architects files at UC next time I’m in.

Colin Lamb designed the wonderful Ovaltine Factory in Papanui Rd (1944-46) – it then became the Helene Curtis Factory (hair products, I think) and most recently Foodstuffs Head Office in the SI: https://goo.gl/tbT7yS – it’s Amsterdam School Dutch Brick Modern. Mucked around with but still recognisable.

Thanks Jessica and (indirectly) Guy. Yes, it seems most likely that the architect was in fact Colin Lamb, not Charles Lamb, as Colin Lamb was designing Art Deco style buildings nearby in Waimakariri –

http://landmarks.waimakariri.govt.nz/lost-heritage/rialto-theatre

“The Rialto Movie Theatre was built in 1935 for H Owen Hills. The clean lines and geometric designs on the outside of the building are typical of the Art Deco style. Colin Lamb, the Architect, had only recently returned to New Zealand from studying in England and America. While abroad he had many opportunities to examine the most modern theatres and the principles of their construction†[Press 2 August 1935, p. 8]. The reinforced concrete construction complied with new legislation following on from the 1931 Napier earthquake.”

Also http://don-donovan.blogspot.co.nz/2011/08/new-zealand-odysey-kaiapoi-community.html

Demolished 2011, sadly.

from the Press on 2nd August 1935…. “NEW THEATRE FOR KAIAPOI – BUILDING OF MODERN DESIGN

Work on a new picture theatre for Kaiapoi will begin at once. Of the semi-stadium type, it will have a seating capacity of approximately 450, with a small dress circle of 100 seats. In compliance with recent legislation reinforced concrete will be the construction to give resistance to earthquakes. The proprietor of the new theatre is Mr Owen Hills, who has secured the services of Messrs Haines and Lamb as architects. Mr C. C. Lamb, after five years’ absence, has just returned from study in England and America.

While abroad he had many opportunities to examine the most modern theatres and the principles of their construction. One such building was the International Music Hall, Rockefeller Centre, New York, which is America’s largest cinema, seating’ 6200 people. The theatre has been designed to give every seat a perfect sight line and undistorted view of the screen and stage. The stage is sufficiently large for small theatrical shows, with accommodation for necessary stage equipment to give an up-to-date production. Careful thought has been given to the acoustic properties of the building. The builder is Mr W. Williamson. It is expected that the work will be completed by November of this year.”

We’re getting closer… (well, I am anyway…). From the Press 27 April 1937:

“NEW BLOCK OF FLATS IN CITY – USE OF GLASS IN WALL SPACE

“Work is to be started immediately on the construction of a large block of flats with garages, to be called the College Court Hats, which will be erected at the west end of Cashel street near the Botanic Gardens. A contract has been let to Messrs J. W. Beanland and Sons, contractors, and the building is expected to be finished and ready for occupation in about six months.

“The block, comprising 11 flats, will be the most up-to-date in the west end of the town, every flat having a separate entrance and a separate back yard, but their special feature will be the amount of glass to be used. The architect’s drawings show that about one-half of the north and west wallspace will be in glass. The amount of glass to be used is probably greater than in any other block of flats in the city. The architect is Mr Colin C. Lamb.”

He also designed the Hollywood theatre in Sumner… according to the Press, 9th April 1938.

“The opening of the new Hollywood Theatre at Sumner Is above all an indication of the progress which this up-to-date borough has made in recent years. The design of the theatre, internally and externally, is also in keeping with the high standard which the borough has maintained in its buildings, both domestic and business. The management of this new theatre has taken every advantage of the rapid advancement being made in theatre design and technique, with the result that Sumner will be able to lay claim to having one of the most up-to-date theatres in the Dominion. The building itself is of reinforced concrete, designed along the lines of the stadium class of theatre; it has a large seating capacity, with special de luxe seats in the stadium gallery; there is a tastefully decorated lounge foyer, with provision for a snack and milk shake bar, and every other amenity. Plush seats are provided all over the theatre, and an air-conditioning system ensures added comfort for patrons. The arrangements in this respect provide for controlled temperatures, with warm conditions in winter ‘and cool ventilation in summer. The theatre makes a very fine addition to the already extensive amenities available in this progressive suburb. The theatre will be opened by the Mayor (Mr J. Tait) this evening. The architect was Mr Colin C. Lamb.”

“A special attraction for the children—the popular Flash Gordon Serial — will be shown every Friday evening and at the matinee on Saturdays.”

…and here he is at last, on 20 May 1935 in the Press:

“BUILDING IN NEW ZEALAND – ARCHITECT IMPRESSED After spending five years in England and on the Continent studying modern architecture, Mr Colin Lamb, who returned to Christchurch on Saturday, was pleasantly surprised with the progress revealed by some of the latest buildings in this country. Some of the most recent Christchurch buildings, particularly the new State Fire building, the Avon Theatre, and the women’s rest rooms, he considered very successful in design and execution. Mr Lamb, previously of Christchurch, is now registered as an architect in London. He has lived in England for the greater part of his five years abroad, but on his return to New Zealand he took the opportunity of visiting New York and Chicago, where he was well received by leading architects, and where he was shown over some of ihe largest and most modern buildings. After leaving Chicago. Mr Lamb travelled through Canada, and he had the pleasure of meeting the New Zealand Prime Minister (Mr Forbes) and his party at Banff.” p10.

and some more for you m-d…. from the Press on 11 July 1935

“General News – A Reply from Mr Shaw

“An amusing and characteristic letter from Mr Bernard Shaw is in the possession of Mr Colin Lamb, the New Zealand architect who has recently returned from abroad. Soon after Mr Shaw had come back from Russia Mr Lamb was offered a position by the Soviet Government as an industrial architect in Moscow. He wrote to Mr Shaw saying that he was anxious to get on when in Russia, and asking for letters of introduction which might enable him to get out of the rut as a mere assistant and gain a better position. The following reply was received from Mr Shaw’s secretary: “In reply to your letter of the 23rd instant, Mr Bernard Shaw asks me to say that men who are determined to get on are shot in Russia, and that introductions are considered bourgeois. Better leave all that behind in England.”