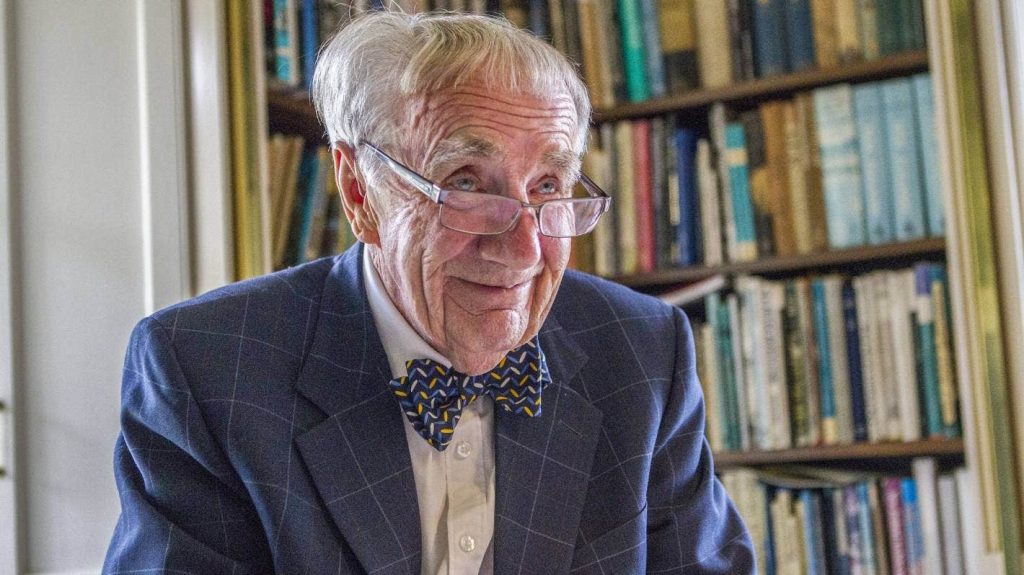

Sir Miles Warren died on Tuesday, the last of our knighted architects. He was 93. A prolifically talented architect, he and his practice were without doubt the major architectural force in Christchurch, having built much of the city through the 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s. Warren and Mahoney were THE architectural practice of the South Island for those decades, and indeed for much of New Zealand. In the 80s WAM extended north and built in the North Island as well, and overseas too, with Miles’s easily recognisable style spreading its wings and taking flight to a few places abroad.

It would be great if the current employees of the modern variant of WAM would leap in here and make some commentary as well, but I doubt that will happen – they keep a notoriously tight ship and spring no leaks. But please correct me if I get details wrong.

I only met Sir Miles a few times – he gave a lecture to us in Auckland once, he spoke in Wellington as well on a few rare occasions, and I think we went to see him in his home town which he loved with a passion. And of course at his house – should I say, his castle? – Ōhinetahi homestead and gardens – on the hills near Christchurch. Always welcoming, always warm and friendly, always with incredibly bushy eyebrows and well-spoken to a T, Sir Miles was a very clever businessman as well as a talented architect. Warren and Mahoney were never officially the Government Architect, but Miles secured so much of the country’s biggest, most important contracts that they may as well have been – a trait that continues to this day, where WAM continue to scoop the pool.

The Press in Christchurch notes that:

“His practice went on to design a series of high profile buildings in the city, creating a form of brutalist architecture that became known as the “Christchurch School”. Major projects in Christchurch included College House, Harewood Crematorium, the practice office in Cambridge Tce, Canterbury Students Union, and the Christchurch Town Hall. The practice also designed the Civic Offices in Rotorua, Television New Zealand Network Centre in Auckland and the Michael Fowler Centre in Wellington. He retired from the practice in 1995 but remained an active advocate for architecture.”

Yes, of course, he was famously the architect of the Sir Michael Fowler Centre, the Wellington version of the Christchurch Town Hall with so many similarities on both the inside and the outside. We will forever owe that to him – a superb venue with great acoustics – uncomfortably close to our Old Town Hall. Warren and Mahoney also created many of the commercial office towers of the 80s, certainly in Christchurch, and even a few in Wellington and Auckland, but I think it is fair to say that the Post Modern style selected back then has not lasted well. Many (Most? All?) of the 80s PoMo monsters have fallen in the Canterbury quakes, which is probably a good thing in the end – some truly hideous towers that will gradually fade from memory. But he also designed some superb office towers, well planned, excellently functioning, and always impeccably stylish, much like Sir Miles himself.

Sir Miles Warren was best, perhaps, at housing projects, excelling at the practice of arranging space and concrete block into pleasing proportions and making some fantastic homes. He was a superb domestic architect, carefully crafting space out of solid geometric chunks, nearly always finished in crisp white paint or boldly bare concrete.

Website 180 gadgets (no, I’ve never heard of it before now, either), notes that:

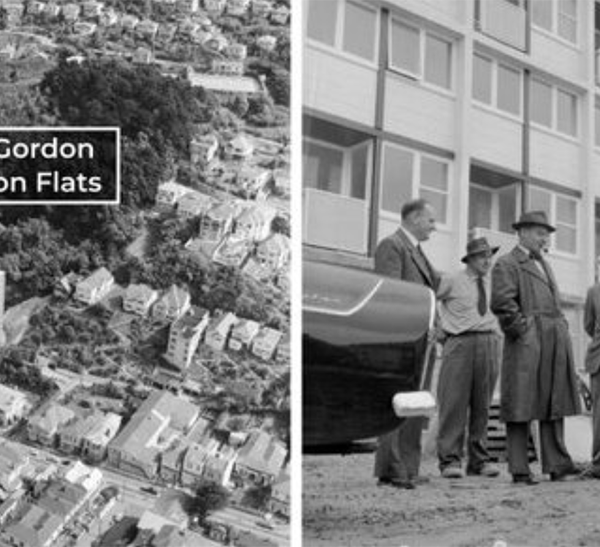

“Born in Christchurch in 1929, Warren started his working life at the age of 16 within the workplace of Cecil Wood. After initially learning structure by way of correspondence at the Christchurch Atelier, he moved to Auckland to finish his research, then travelled to England in 1953. There he laboured with the London County Council and was, in his personal phrases, “extraordinarily fortunate to be sitting right in the middle of the birth of Brutalism”. Influenced by his first-hand expertise of the work of Scandinavian architects corresponding to Finn Juhl, Warren returned to New Zealand “brimful of ideas” and commenced designing a few of his most iconic buildings. He began his design follow in 1955, starting with the design of two homes in Timaru in that year. In 1956, he designed the Dorset Street flats in Christchurch, and in 1958 he started an extended and profitable partnership with Maurice Mahoney, successful a big contract to construct the Dental Training School.”

What I think is a little sad is that the press have never acknowledged his sexuality. Do we still need to be coy about such things in the 2020s? Shouldn’t we also be proud that a gay man was one of our best architects ever? It was no secret really – fairly obvious when you talked to him, and for many years the practice was infamous for only employing young men from Christchurch’s Christ College, Miles never married, and lived with his sister on his wonderful Ōhinetahi property. Is this the first time it has been acknowledged in print? Is it important? Well, no, it shouldn’t be, but I think that his abilities may have gone hand-in-hand with his gayness. Many of the world’s best architects are gay, either openly or still closeted away, in the same way that artists, actors or dancers are often gay and only just starting to open up. Sir Miles was gay and probably all the better an architect for it. Others will know more, perhaps first hand experiences with it, but as far as I know he was more inclined to be married to his work, being an excellent draftsman and possessing a beautiful ability to think things through in three dimensions.

My favourite Miles detail is perhaps the corbel, which he rescued from its ancient roots in castle design from a thousand years ago, and made into such an integral part of his architecture. If you look carefully, nearly all his architecture possesses corbels to some extent. On small houses, a corbel would project out from a wall, only to gratefully receive a descending rafter or beam, often at a jaunty 45º and the corbel would take that load and carefully transmit it down into the wall below. It is a lost art to most architects nowadays, and distinguished Sir Miles work from that of his arch-nemesis, Peter Beaven, who was the other major protagonist in the Christchurch School, which “melded the solidity of New Brutalism with the light-weight vernacular of the Group Architects.”

His generosity and lack of descendants means that he has given away much of his wealth that he accumulated – first of all by establishing the Warren Trust in conjunction with the NZIA, where a substantial portion of money was given to establish a trust where writers / books on Architecture could be funded. Most of the architectural books produced in NZ have had some funding from the Warren Trust – so thank you Miles, for that. But secondly, and most importantly of all, he poured his life (and his money) into the Ōhinetahi property, both before and after the earthquake. Luscious, formal gardens combined with a two storey high stone historic house, which unfortunately came crashing down in the first big Canterbury quake, nearly killing Miles, but fortunately sparing his life. Undeterred, he dusted off the drawing board sitting in the corner and proceeded to rebuild the stone part as a one storey building, creating some brand new heritage along the way. I suspect that Miles knew that to wait for the Historic Places Trust and bureaucracy to catch up would only lead to heartbreak and delay – so he went ahead and did it anyway, I think even ringing his favourite contractors the same day to secure their services. A pragmatist as well as an exuberant architect, New Zealand’s architects have truly lost a wonderful leader of the profession. The funeral will be next Thursday in Christchurch. Expect a packed wake afterwards. Farewell Sir Miles, and thank you.

Looking at my copy of New Territory – WAM – 50 Years of New Zealand Architecture, (Balasogalou Books, 2005), there is an excellent chronology of the practices work, noting a number of houses in the 1950s and 1960s, a burst into the public realm in the 1960s (too many to list), but you may remember the Student Union in Auckland – they also did the Student Union buildings in Christchurch, Palmerston North, the Maidment Theatre in Auckland (now demolished by the idiots up there), the Waiuru Army Museum, and many many office buildings. Of possible interest to you, there is the Union House, Waitemata City Council offices, Citibank Tower, all in Auckland; Fletcher Challenge House, 49 Boulcott St, Whitcouls House, Bowen House, National Insurance building, Maritime House, Paraparaumu Library, the Cake tin Stadium, a refurbishment of the Beehive in Wellington; The National Aquarium, Scenic Circle hotel and St Patrick’s church in Napier (and several other churches in Christchurch); Salvation Army Citadel in Wellington, the Civic Centre in Rotorua, and of course the gutsy NZ Embassys in Washington DC and New Delhi – to name but just a bare few.

So much work. So much talent. Miles will be missed. A life lived well.

There is a lovely piece about Miles in the Press today by Coleen Hawkes:

https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/homed/latest/129543304/sir-miles-warren-an-architectural-legacy-that-has-stood-the-test-of-time

Speaking of the Ballantyne House, the article notes:

The 300 square-metre house has the concrete block and timber-framed construction that defined the Modernist school of buildings in Christchurch.

“Miles describes it as being essentially Danish in character – a square consisting of a living room, dining room and kitchen, with a long bedroom wing and connecting flat-roofed entrance link.”

A book on Christchurch Modernism produced in 2020 by Mary Gaudin and Matt Arnold (straightlinebook), features several of the architect’s residential projects. The book, “I Never Met a Straight Line I Didn’t Like”, takes its title from a quote by Sir Miles Warren.

A sad loss to New Zealand….a great contributor to our modern society. And also yes, so much of the media keeping Miles in the closet. What a contrast to the endless media stories on NZ individuals that include the person’s marriage, family etc. There’s probably also a story about the culture and class history of Christchurch. Just imagine if the city had opened up to outsiders avd external expertise after the quakes?

RIP Miles – a sad loss – and one less gorgeous DILF in the South Island,

Goodness ! I didn’t even no there was such an acronym – now I feel edumacated. Aaah, the class history of Christchurch – not something I have ever been a part of (as a North Islander, I guess that automatically makes me forever an outsider to the Mainland). What was the old saying? In Wellington people ask you what you do, in Auckland people ask you how much you earn, and in Christchurch people ask you what school you went to? Something like that. And Miles famously went to Christ’s College, and was the architect of record for all the work they did to the school, and employed their brightest and best young male talent – no wonder that WAM have a certain air of entitlement. Perhaps not any longer? Or perhaps, now more than ever? Anyone from WAM care to comment?

A curious thing – every time I go to write Miles, I find my fingers tapping out the word Mies instead. An architect’s conundrum, a first world problem, I know, but I guess that Mies and Miles were alike not just in name but also in being the diehard pinnacle of modernist perfection. Fortunately for Mies van der Rohe (a uniquely Maori name for a German !!) he passed away before the foolishness of the Post Modern era, and unfortunately for Miles (Imperial Rabbit) Warren, the Post Modern hit hard. And not in a good way. Thanks to Alan for the larger list – but I don’t think many people will be mourning the loss of some of those awful POMO pieces that fell after the quakes. Clarendon Tower anyone? And then there is Bowen House and the exuberance of Boulcott St too – let’s close the door on that unhappy valley.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/129619296/stirring-send-off-for-architectural-giant-sir-miles-warren

Well that’s interesting! I thought that Stuff might have some footage of the actual funeral today, which I missed, but instead they have a video of the massed ranks of the boys of Christ’s College – doing a haka. I expect Miles would have been beaming from ear to ear, and mumbling “Goodness me” to himself as the hearse slowly moved on. I think that Sir Miles smile was one of the loveliest things about him – always warm and friendly (possibly different if you worked for him?). I’ll see if I can find a recording of the eulogy if there is one.