I’ve always been a fan of this painting:

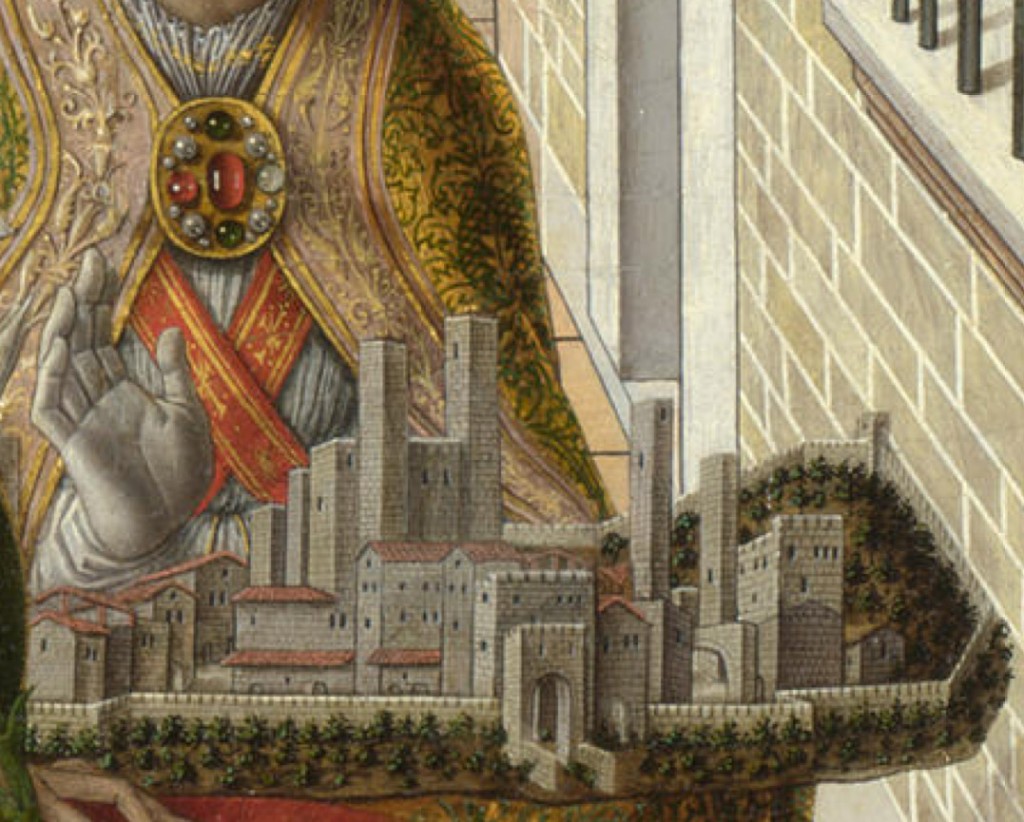

Carlo Crivelli’s painting of the Annunciation, with Saint Emidius, is an architect’s dream – a one-point perspective of stunning richness of detail and depth of colour. Dating from 1486, and held in the National Gallery in London, it depicts the town of Ascoli (in model form on the knee of Saint Emidius), as he chats about town planning matters with the Arch Angel Gabriel.

It’s no doubt an early form of the pre-App meetings so fondly promulgated with our local council, although I must say, the Council urban design officers do not normally dress quite as flashily as Gabriel (unless perchance it is Tom Beard), nor sport such a groovy multi-colour pair of wings.

Meanwhile, inside, our beloved erstwhile, virgin Mary is getting smote through the skull by a flying pigeon. Peow peow, straight on her forehead. Shot!

Most of us get rather annoyed when a pigeon craps on us, but this pigeon-dove, in the form of a beam of light shining down from what honestly appears to be a flying saucer, seems to penetrate her head, head straight for her womb, and get her pregnant – even though Joseph is nowhere to be seen, and Gabriel (the purported suspect in the impregnation case) is outside discussing cornice details with Emidius.

Well, I never…

Or perhaps they’re discussing ways of financing affordable housing, for those who can’t afford more than a stable. It’s a far more architectural way of depicting this holy inception, which is normally just all a mass of fluttering wings of rascally little putti, as in this alternative painting of the same scene by Bartolome Murillo:

Delusional young women have always been getting pregnant to forcefully persuadish men, since time began, and the excuses no doubt will keep on coming, but it is remarkable how long this tale has survived. Such a patent load of tosh is puzzling in that a sizeable portion of the world’s population still believes this tale of woe, although I’m glad that New Zealand is one of the most agnostic nations on earth, and bible-thumping closeted critics like Colin Campbell are left wailing scripture in the corners with little attention being paid to him.

But it is details like the carpet design, hung out to air from the window above that are the clincher for me. The detail shows the influence of the Ottoman Turks, with their Islamic pattern repeating in the centre of the carpet, reflecting the recent peaking of Ottoman influence around the same time. The dusty, ochre-based colours reflect the emergence of the craft of dying, the clothes are relevant to the time of Crivelli, and with the architecture of the day on display, there is no thought of trying to depict year Zero on a dusty hillside in Palestine. The Gaza strip this is not.

In the background, a confused looking group of locals stare wildly around them, no doubt wondering what that buzzing noise is from the Saucer overhead, but what we can note as architects is that the brickwork has been given a whitewash, and the contractors have walked off the job mid-way through. Industrial relations have evidently given grief since time immemorial.

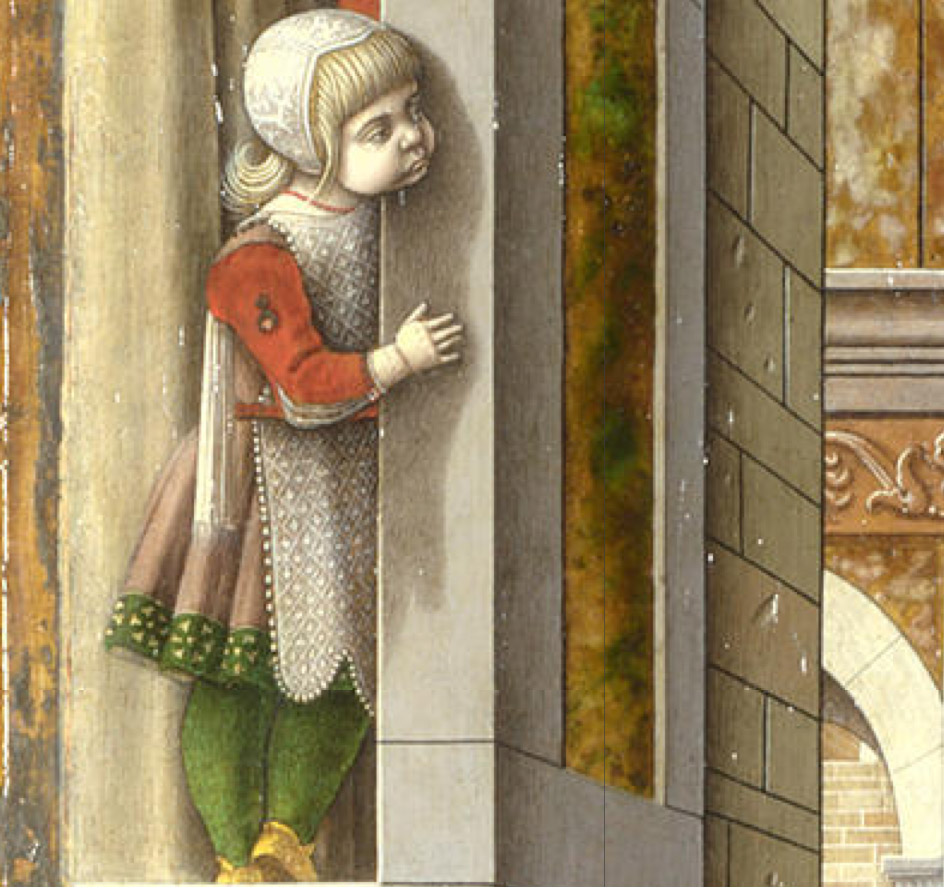

You can read many things into the symbols in this story – my reading is that Crivelli knew it was all a cover-up, and by showing us the brickwork, clearly didn’t believe the whitewash over Mary’s pregnancy for one second. He has depicted a young girl watching, hiding amongst the balustrade of the landing opposite (no child-resistant hand-rails there!), and I think that Crivelli is saying that she has seen the truth. of course, what the actual truth is, is up to your own interpretation.

In the mean time, his obsession with detailing the cornice line indicates a healthy interest in becoming an architectural technician, and a half-decent use of CAD package 0.0 as well. There are some pretty serious fretwork details along there, as well as the cage of iron bars that are locking our delicate virgin away from all the neighbourhood boys. Indeed, the whole area depicted is a tight little display of Urban Design precinct that beats Chews Lane hands down with reference to urban interest.

The last word though, goes to the objects left casually on the frontispiece in the foreground. There is an apple and a cucumber, both curiously three dimensional, as if being offered for us to pick up and take away.

The National Gallery website has a historian Gillian Riley tell us a tasty treat that the apple is symbolic of Mary, although to me it must surely always be linked to Eve; and that the nasty, spotty, lumpy, penile protrusion is a cucumber symbolic of Christ himself, which seems unlikely, and a bit harsh, given that it is clearly a pickled gherkin and fit only to be sliced ready for burgers.

None the less – for a 600 year old depiction of Italian hill-town life, it is just lovely. An obvious reposte to this painting of Mary updated into a scene of Crivelli’s contemporary time-zone, would be to paint a version of what a modern young virgin would look like being impregnated by the hand of God, in a typical New Zillun suburban paradise, as she piously crouches over her homework, listening to One Direction on her Apple iPod, with parents nowhere to be seen, and the local Bishop outside discussing drainage plans with the man from the Council, about the garage extension out the back.

Sigh. Not such an inspiring vision. It’s back to the cook books for me.

Inspiring picture! One question from me though – if the colours are so good, why does the peacock have a yellow tail? Shouldn’t it be green and blue?

Well, the same person who talked about the cucumber, also talked about the peacock. Apparently, peacock flesh lasts for a long time – it’s almost immortal. Sounds icky and smelly to me, but apparently this meant that in some people’s eyes, that a peacock was like Christ, re the immortality bit. Makes you think twice about the whole “this is the blood and the body of our Lord Jesus Christ” bit.

Therefore, I’m guessing that rather than the peacock being a different species of northern Italian roof-climbing peacock, this peacock is not just yellow, but is in fact Gold, ie being worthy of the Son of God etc.

As the quote says-

“In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed – they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love and five hundred years of democracy and peace, and what did they produce? The cuckoo clock!”

Max your contrast between what I’ll call the low art of suburban Noo Zild and the high art of Crivelli seems to show that your aesthetic side is suffering amongst the dreck and cant of bad 90’s developer architecture.

Would you rather live in the kind of society that was Crivelli’s mileu? That’s a tough world right there, no working for families, no pensions, not a whiff of ACC. They were left to the immortal words of Julie Burchill – “Cream rises, crap floats”

So maybe this place isn’t destined for high art so much.

In this country the best things, the oldest things are natural, not fashioned by human hand. Our cathedrals are the forested mountansides and alpine slopes. Tane Mahuta is our Nelson’s column.

If you choose to live here and want to experience the best things that this country has to offer then scenery will do more for your sense of peace than gazing upon appalling things (ie Churton Park)

If you’d like a local example may I recommend the 800 year old Rimu in Wilton Bush (Yellow trail across bridge North from Troop lawn) or, if you want to impress your date, the glow worm walk in the Botanic Garden from the bottom of Glen Rd in Kelburn down to the duckpond and back – best in the summer, that one.

But if you really need your fix, you know that this exists, right?

http://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/project/art-project?hl=en

60 – my heartfelt thanks for that link – no, I did not know it existed, and I’m sure I will enjoy many happy hours linked into that treasure-trove of art. And re the natural on (free) display in NZ – fair call. Thanks!

You missed the most intriguing architectural element – the little arch cut into the frieze, by which the holy ‘virility beam’ is shot down upon our fair virgin. Now there’s some architectural forethought, as I can’t imagine too many other uses for a such an obliquely angled channel through the solid masonry wall.

The groceries stand in for, according to my sources, virility, and the original sin. It’s not hard to guess which is which…

And, regarding your barred window thesis, it may just be possible that the knowing little boy (apparently), has recognised the fact that barred windows present no particular obstacle to young men of lecherous intent when the virgin’s boudoir helpfully presents a large aperture directly onto the street, without so much encumbrance as a door to control entry therein. Even the maidenly mattress is revealed to passersby…

Oh – and it’s not quite Churton Park, but there is this:

http://blogofthecourtierdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2009/03/annunciation3.jpg

But this one probably satisfies your ‘pessimism’ much more:

http://asset3.itsnicethat.com/system/files/062012/4fd50ad05c3e3c472600109c/img_full_width/GPHERO.jpg?1354576227

(it even has vegetables)

Aaah yes, m-d, i had seen the John Collier painting of the schoolgirl Annunciation before. There is also this one by Duane Michals:

http://www.deborahkuschner.com/dynamic/artwork_detail.asp?ArtworkID=16

or this one of the Annunciation in a more modern form, by Gottfried Helnwein:

http://hellburns.blogspot.co.nz/2012/01/modern-annunciation-by-gottfried.html

I too had noticed that little yellow aperture through the entablature, and wondered of its uses, apart from the fore-mentioned divine solar ray piercing Mary’s furrowed brow. But one thing that you and m-d do not seem to have noticed, is the white stripes of a zebra crossing on the street in the middle distance. Crivelli seems to have invented the pedestrian crossing before the Italians had invented the car, let alone the cuckoo clock. One other thing you forgot to mention Max: the curtain rods hanging out in the street – what do you make of them?

Aah but they aren’t curtain rods, they are for the birds to sit on.

Also seeing as in Crivelli’s world the birds don’t appear to have crapped on anything, perhaps they used the straight rods to train the birds to shit down the street in a line, thus creating the stripey motif

Either that or they use those fricken lasers