The Wellington Town Hall is getting strengthened and some people are getting exasperated at how long the process is taking. To be fair, the building has been sitting empty, closed off for a number of years now, and only recently (2018) has it actually been behind work hoardings. So – what is likely to be happening?

We’re not completely sure, but here at Eye of the Fish we understand that the refurbishment architects may be Athfield Architects, although we are unsure who the structural engineers are. Consequently, we can freely admit that we may have all the following wrong, and we are open to being corrected. First of all: let’s look at what we do know.

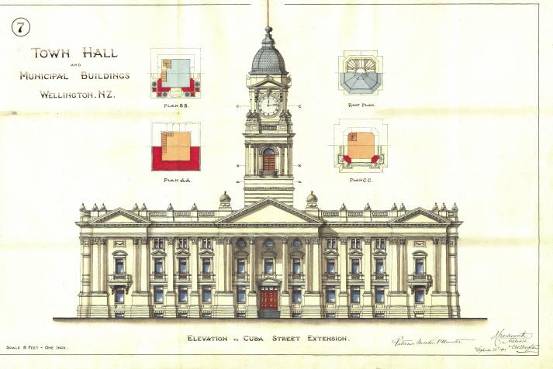

The Town Hall was designed by Joshua Charlesworth (1861-1925), a Yorkshireman who came out to NZ on a ship when he was an architectural intern. His boss had designed large buildings back in the UK, so it is possible that Charlesworth had some experience with this sort of work, but while Charlesworth designed some houses in NZ, for the most part he worked on a large number of small commercial buildings for the BNZ throughout the lower North Island.

Charlesworth was a bit of an architectural hot-shot, winning (in his twenties) a national competition for the NZ Government Insurance buildings in Wellington over some far more experienced architects like Turnbull. He left NZ to work in Melbourne for a number of years, gaining experience on larger projects there, but returned to NZ for the Town Hall project. It is still a fair bet to state that the Town Hall project was the biggest project Charlesworth ever did. The Wellington Town Hall construction contract was signed for £68,000 in 1901, it was completed and opened in 1904, although the clock was not fitted into the clocktower until 1922.

Luckily for us, the Town Hall project was built well, with a massive thick brick and stone external wall surrounding a rectangular auditorium with a timber floor and plastered ceilings that offers surprisingly good acoustics. Whether by chance or by good design, the Charlesworth-designed Town Hall has a superb sound and is well worth keeping. Part of this comes from the rectangular shape, part from the proportions, and part also from the larger, massive brick external enclosing structure. Composed of Corinthian columns supporting two large pediments, it also used to house a massive brick clock tower as well, sited on the side where the Michael Fowler Centre is now.

After the 1931 Napier earthquake the clock tower was removed in haste (well, 1934) by Field & Hall, when the WCC realised that it could yield and fall, catastrophically, in the case of another closer quake. Many of the ornate Corinthian columns were also stripped of their floweriness at this time, with many reduced from Corinthian capitals back to the simpler, lower Doric order. That’s the building equivalence of taking off a ball gown and wearing army fatigues instead.

Due to the age of the building, there is not a full steel frame or concrete frame in the building – although of course there are some cast iron columns holding up the balcony in the main auditorium. In the early 1990s Fibreglass Developments Ltd (FDL) were tasked with rebuilding some of the removed capitals, but in fibreglass, not brick and cement. This is all part of the move to lighten the building – to reduce its mass – to increase its chance of survival in a large quake. Of course, in a really big quake, a building made of bricks is just not going to make it. As we have said before, Unreinforced Masonry is Not Your Friend.

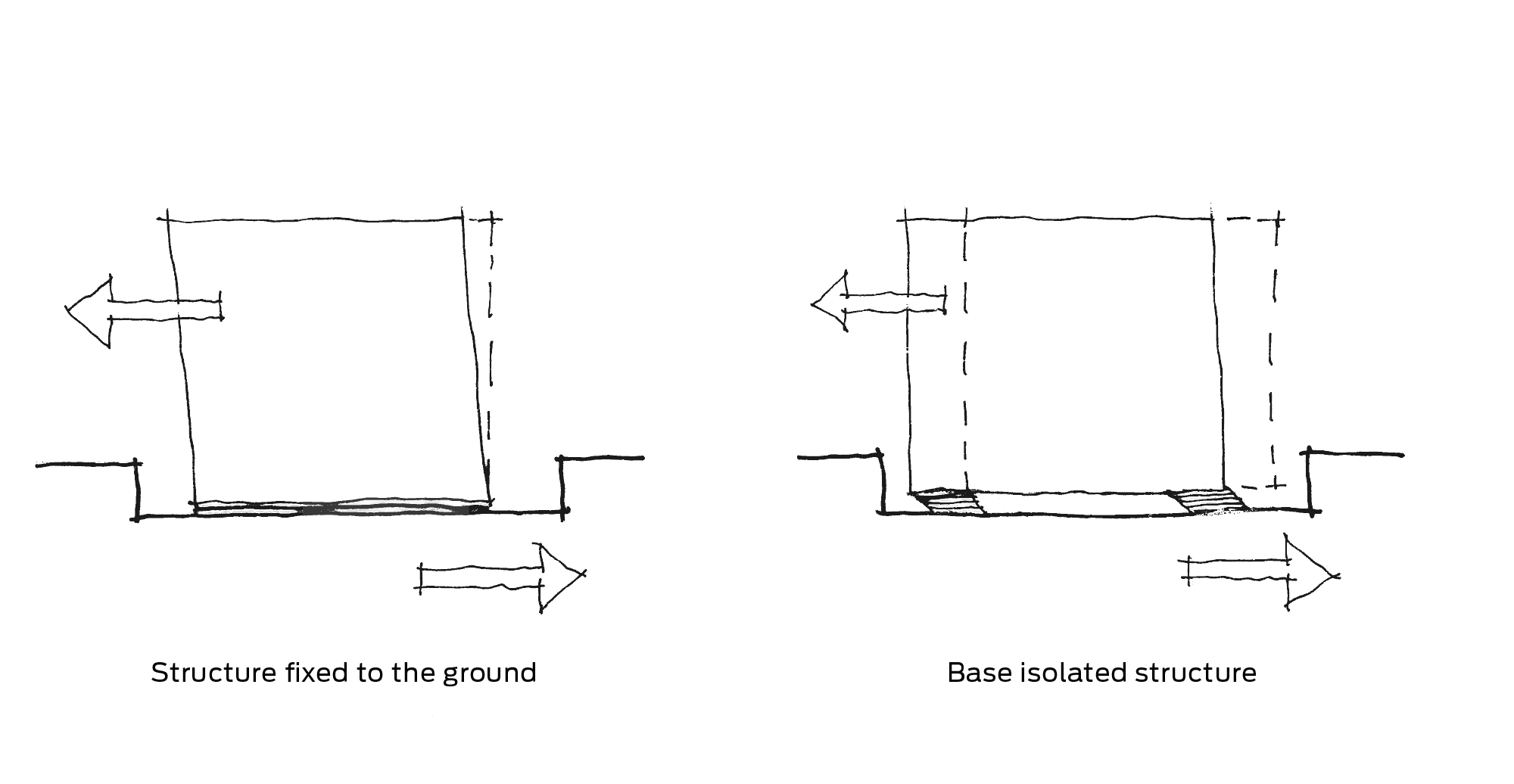

The structural strengthening works being done now are planned to provide base isolation to the entire structure – no easy task – but also the best possible solution to ensuring the long-term survival of the building. You probably all know that this base isolation entails inserting isolating bearings between the building and the ground – we’re not sure what sort of base isolators they are using, but they could well be the same sort as used in Te Papa, with a lead core within a steel and rubber block. The picture below shows Dr Bill Robinson (the inventor of base isolation) with an isolator being installed at Te Papa.

The thing with base isolation is that it needs to be placed securely between two very firm layers – typically this is between the top of a pile and the bottom of a beam. The problem for the Town Hall is that neither the beam nor a strong pile exist at this stage, so these need to be installed first. Sounds simple, but it is not. The workload will go something like this:

• Pull up the entire ground floor and expose the foundations (this has already been done).

• After this, the super-structure needs to be cut free and completely separated from the foundations below, with a brand-new ground beam installed, over brand-new foundations. Way easier said than done.

• With a new building, the foundation piles are installed first on a bare and empty work site, reaching deep into the earth until they reach the bedrock below. Once that is done, the new ground beam is installed over the base isolators, leaving a clear gap all the way round the perimeter. Only when that is complete is the rest of the building constructed on top.

• With strengthening of an existing building, that logical order of things is turned upside down. The contractor will first need to progressively work around the perimeter of the building, under-pinning the existing brick external façade. Due to the thickness of the wall, this is a tricky task and will need to be tackled from both inside and outside at the same time, drilling holes through from one side to the other and poking steel beams through. They will need to do this in patches, supporting the brick wall with temporary steel beams sitting on those earlier steel beams like a game of giant steel Jenga, while they dig out room for a segment of the new reinforced concrete ground beam below. It is quite likely that only when this ground beam is in, that the foundation piles can be installed.

• Even the piling will not be straightforward: the bulk of the building will be in the way. It could be that piles are installed both inside and outside and connected with a thick strong concrete pile cap. That would entail a piling rig is used close to the existing building on both the outside and the inside – more tricky on the inside obviously – which may mean they have to use micro-piling, with shorter segments of piling connected together. The piling to the area below the auditorium floor will be much easier – with the floor all ripped up, they can pile in the open, straight down. There will need to be a lot of excavation of course, digging out metres of mud and sand – this is a reclaimed waterfront site after all, so there may well be archaeological remains below. Certainly there will be lots of seashells.

• Only when this immense sequence of works is complete, around the entire perimeter and around the interior as well, will the building have been separated. I’m guessing that they don’t wait till the end to install the base isolators but that these are inserted as they go, but even this is a little tricky. You really don’t want a building to be half on wobbly rubber bases and the other half still fixed to the ground – given a good shake, the building above will rip itself apart. What will need to be done however is that a trench – or moat – is dug right round the perimeter, about half a metre wide. Again, a bit easier said than done, when the Town Hall sits right next to the Council office building next door.

• All of this work needs to be done before any of the upstairs can be renovated and converted into a School of Music suitable for Victoria University.

Given that there are a limited amount of people capable of undertaking this sort of work in NZ, that space will be cramped and access restricted, I’m not at all surprised that the program of works will take a long time, or that it will be hellishly expensive.

One of the minor pluses is that there is “some” underground access to the building on the civic square site, which in reality is basically the lid to a large underground carpark that runs from the steps of the City to sea bridge all the way through to under the library, there is a large dockway which is linked to the large floor access lift in the town hall main auditorium…

That’s were the ramps beside the Michael Fowler Centre, and on the other side of the crèche all end up…..

greenwelly – aaah, of course, thank you for that. Didn’t know that. I’m thinking – there’s a whole lot of demolition going to go on down there…. Civic Square needs a revamp, in a BIG way….

Report from RNZ via Scoop: http://wellington.scoop.co.nz/?p=118080

About $15 million has been spent preparing to strengthen the Wellington Town Hall before construction work has started.

Mayor Justin Lester said it’s normal for that amount of money to have been spent on designing and signing off on such an expensive project. Earlier this year it was announced the cost of strengthening the hall had gone up for the fourth time, to at least $112m.

Since the town hall was closed in 2013 for strengthening, the cost of the project has gone from $43m, to $60m, to $90m. The final price is expected to be higher. The money spent so far had been on planning and design, Mr Lester said.

“We want to make sure that Wellingtonians get a good outcome, they want a strengthened town hall in a building that’s going to be here another 50 to 100 years.

“That’s why it’s going to be base isolated. It is on reclaimed land, it’s a category 1 heritage building.

“It’s a complex project, that’s why you have to invest in the planning and design up front.â€

Mr Lester said $1.6m of the spend went on securing the building’s masonry, as legally required. And $4.8m had been spent for design work and consultants on an earlier iteration of the project that was cancelled in 2014.

Just to clarify matters, in case you had a query: the photos of under-pinning and piling etc are NOT of the Town Hall project – just examples of the sort of difficult stuff that the contractors will have to do.

Also – I think I saw a headline today: Naylor Love have been appointed as the Contractors. A good, reliable, well-capable company of contractors. Hopefully we are in safe hands here.

Here’s the announcement of the Naylor Love contract, which has since been signed. http://wellington.scoop.co.nz/?p=116610