The local media hasn’t caught up with this just yet, but we have just seen the greatest loss of architecture since – well, I don’t know. Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s masterpiece of design, the Glasgow School of Art, caught fire yesterday, in preparation of the 4th year final degree show. Sparks on foam, in the basement, and as flames were filmed breaking out of the roof, for a number of hours, then i think that we have to presume that the building has effectively lost all it’s wonderful wooden interiors – hundreds of aged Scottish oak furniture fittings, a wonderful wooden library, and of course all the work of all the students preparing for year end reviews.

It’s a sad, sad day. It’s also amazing that the school appears not to have a sprinkler system installed – how can you have a internationally acclaimed timber-lined monument filled with working students and essentially neglect to retrofit a sprinkler system? Heads will roll, no doubt, but too late is – well, just too late. The stonework may survive, but the oaky timber-work will all have gone skyward in plumes of smoke.

I’ll try and post some pics up here later, but they will be all over the foreign media already – but I’ve got to confess that I am a little confused. I actually was very soon going to write a post on the despoliation of the building by architect Stephen Holl, who has built a giant rectangular overbearing shape above the building, and when I heard about the fire, I immediately thought of the new building work causing the destruction of the old – but when I checked the pictures, there’s was no addition there! Where’s it gone?

Clearly I need to do some more research, as Holl’s butt-ugly awful addition has clearly been built on top of some other Mackintosh building, not this one – but in a way, this is a double tragedy for the Scots – two of their best Macs ruined, one by fire, the other by architecture. More on this story as it comes to hand – or, pipe up and chip in if you know the answer!

Post-script: OK – I was sort of right and sort of wrong. Holl has built a new wing – a massive extension, directly across the road, which was to look out at / over the original Mac building, and now may just be going to look out at a ruin.

Instead, I guess, they now just have to be thankful that they have already built the Holl building (described as the Serona Reid wing?) and will therefore have somewhere to house the students next year. Exactly what they do about marking of all the student work they have just lost, who knows! A+ for everyone I guess! And next year’s bunch of students will learn all about demolition and rebuilding of a masterpiece…

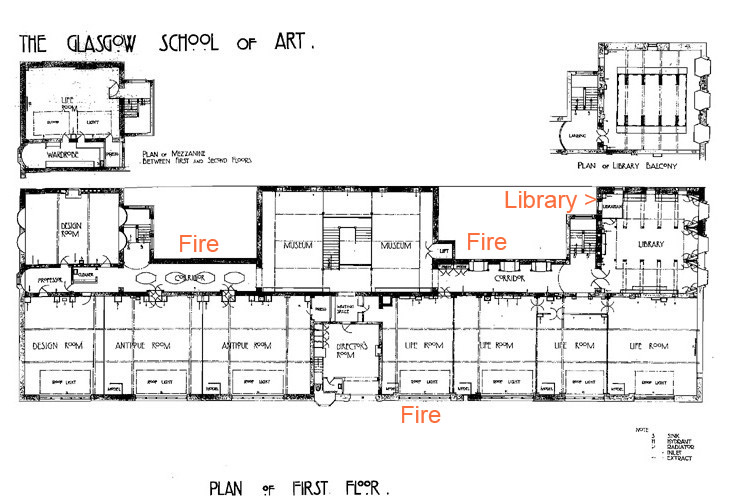

Post-post-script: There still seems to be a lot of confusion as to whether the Library has been destroyed, or if it has been saved. Conflicting reports. I’ve included a plan and a couple more pics, in my efforts to find out what has happened. There is flames and smoke pouring out these windows (below) and at first I thought they were the Library windows (and hence nothing would have survived that inferno) but now I’m wondering if they were the corridor windows, and just aren’t showing up on the plans. Anyone know?

…

…

Seems Holl’s hulk looms across the road:

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/mar/02/reid-building-review-mackintosh-glasgow-school-art-steven-holl

And a pedantic note on behalf of my Scottish grandmother – it’s Mackintosh.

Thanks Starkive – and yes, I was just updating my earlier post. Sad day huh?

May I say – congrats on the Film Archive getting a coup of running the TVNZ archives – that’s a whole lot more work for you guys! http://wellington.scoop.co.nz/?p=67459

I thought you were busy enough already…

And if you want to have a really good, interactive look inside the Library (last chance you’ll ever get!) then there is a 360 degree interactive viewer here, which is almost as good as the real thing. Almost.

Actually, now, it’s probably better!

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/interactive/2011/sep/09/glasgow-school-art-library-360-interactive-panoramic

Maybe there’s better news to come:

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/may/23/glasgow-school-of-art-fire-library

I’m not sure what 90% structurally viable actually means. Perhaps one of your engineer followers could speculate. As for TVNZ, the Elegant Shed must be in there somewhere…

Yes, I too have heard that “90% of the building” will be alright. Of course – it is made of stone – granite from Stirling, if I remember right. Thats the structural bit that is ok. But since the fire started in the basement and worked its way up through all 5 floors…. Id say theyre dreaming. But all the interiors are lined with wood – with beautiful, aged, oak, stained with a patina of time, and with CRM’s handiwork on every detail. They’re going to have a bugger of a job recreating all that – unless they have been training the students at the school how to handadze individual planks. But I bet they’ll install some sprinklers this time….

Re the Elegant Shed – I wonder if they will get Dave Mitchell a dinghy in Venice?

There is more about it here in the Scotsman newspaper: http://www.scotsman.com/news/education/fire-engulfs-iconic-glasgow-school-of-art-1-3421067

Apparently voted in a RIBA poll, the best building of the last 175 years, and the People’s favourite. That’s Princess Diana popularity levels!

And the latest, tragic headline from the Scotsman paper:

GLASGOW School of Art was due to have a fire safety feature installed this summer, the school has revealed.

The school, which was severely damaged by a fire that ripped through the building on Friday, said the fire suppression system would have improved the building’s fire safety measures. But the school admitted that it would have been impossible to know whether the upgrade would have made any difference.

The exterior of the building and many of its contents were preserved by firefighters – but the art school’s iconic Mackintosh library has been destroyed. Around 200 firefighters were dispatched to the scene when the fire broke out at around 12.30pm on Friday.

Culture Secretary Fiona Hyslop said the fire was “truly heartbreaking†and pledged that the Scottish Government would “support the funding effort requiredâ€. Danny Alexander, Chief Secretary to the Treasury, said the government would pledge “millions†if necessary to the restoration of the building.

http://www.scotsman.com/news/scotland/top-stories/glasgow-school-of-art-was-due-fire-safety-upgrade-1-3422267

Too bloody late I say !

Unthinkable? Glasgow Without Its School of Art

05/24/2014 Guardian (UK)

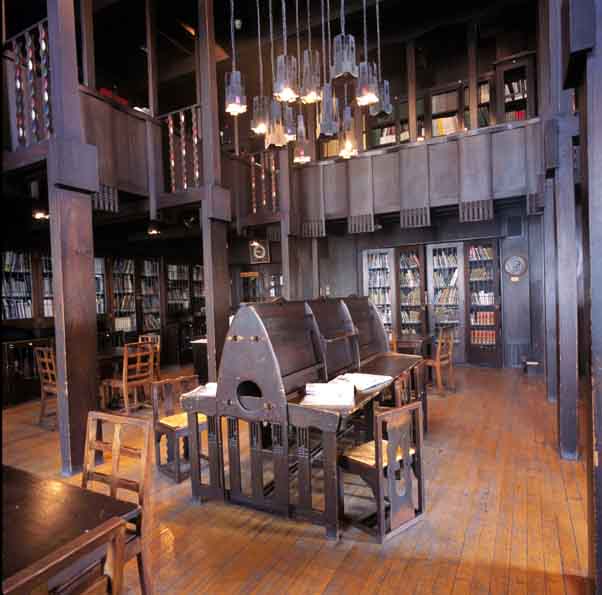

As flames licked through the windows at the top of the Glasgow School of Art yesterday, and clouds of smoke bellowed through the scrolling art nouveau ironwork, onlookers faced the thought of losing not only one of the city’s finest buildings, but a pivotal chapter of architectural history. Like a rocky Highland outcrop, the school has risen proudly above Glasgow’s handsome grid since the start of the 20th century, half baronial castle, half rugged cliff-face. Built between 1897 and 1909, it was chiselled into shape by Charles Rennie Mackintosh , who drew up the designs when he was 28, a junior draughtsman in a big city firm. Startlingly original, it sampled everything from Celtic ironwork to Japanese joinery, providing students with a dazzling lesson in composition and the craft of making. Its library, now a charred wreck, had the atmosphere of a Shinto shrine, a densely layered thicket of dark timber posts that rose to form a sylvan bower of brackets and beams. It took readers on a journey through dappled light and shadow, from sepulchral booths dotted with twinkling clusters of lanterns, to reading tables lit by three-storey high bay windows. Mackintosh played tricks throughout the building, inverting the usual order of things. As you ascended the staircase, floors got progressively darker, with the uppermost level conceived as a cellar, its low vaulted passage entered through a medieval iron cage. The building’s virtuosity, at least, means that every detail has been recorded – and it must be rebuilt.

Mackintosh Was Just a Junior Draughtsman, Yet He Produced a Work of Genius

05/24/2014 Herald, The (Scotland)

THE Mackintosh building at Glasgow School of Art was the result of an architectural competition.

In 1896, the city firm of Honeyman and Keppie submitted a design from one of their junior draughtsmen, Charles Rennie Mackintosh , for the contest. The budget was pound(s)14,000.

The first half of the building was completed in 1899 and the second half 10 years later. The 1909 intake of 1000 students – full and part-time – produced artists, draughtsmen, designers, architects and painters. More than a century after it opened, Mackintosh’s School of Art remains a working building. It is also increasingly seen as an important architectural monument in its own right and is an A-listed building.

With growing interest in Mackintosh and Glasgow , the School of Art – recognised as one of the architect’s masterpieces – is visited by more than 20,000 people a year. It is home to an extensive range of furniture and fittings, watercolours and architectural drawings by the architect who gave it his name. The school also owns a substantial collection of work by former staff and students and a large archive.

In 2007, a rolling programme of work, costing pound(s)8.7 million, began to upgrade the historic building. Administration offices were moved and restored as studio spaces, extra gallery space was added and its archive was extended and preserved. In 2009, the year of its centenary, a nationwide poll by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) voted it the best building of the past 175 years. It won ahead of the Pompidou Centre in Paris, St Pancras Station and the Natural History Museum in London.

Stephen Hodder , president of RIBA, said last night: “The most important work by Charles Rennie Mackintosh , an architect of international significance, Glasgow School of Art is held in the highest regard by architects and the public alike. Damage to a building of such immense significance and uniqueness is an international tragedy. It is irreplaceable. The RIBA joins our colleagues in Scotland in sending out a message to the students, staff of the school and all those who have been associated with this building over the decades, a message of sorrow and commiseration at this terrible news. It is too early to talk about what happens now, but the institute will do anything it can to help in any way.”

Mackintosh as Muse – By Steven Holl – May 29, 2014

Steven Holl, architect of the Seona Reid Building at the Glasgow School of Art, reflects on the magic of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s 1909 masterpiece in the wake of a devastating May 23 fire.

In 1967, while I was an architecture student at the University of Washington in Seattle, my History of Architecture professor Hermann G. Pundt presented an hour-long lecture to the class on the Glasgow School of Art and the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. It was an unforgettable hour due to Professor Pundt’s enthusiasm and passion.

Professor Pundt had devised his own theory and history of modern architecture. Our yearlong education began with Brunelleschi’s Duomo in Florence and its use of steel in tension; progressed through Schinkel’s Berlin works; went on to Louis Sullivan’s buildings in Chicago; and ended with the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. I remember Professor Pundt’s presentation being so great that we never doubted that this was the true history of modern architecture (a narrative in which Le Corbusier didn’t appear). Mackintosh’s work, and especially the 1909 Glasgow School of Art building, occupied a very emotional and important place in my own passion for architecture from that day forward.

Visiting the building for the first time in June 2009, I was very inspired by the vitality of the school and Mackintosh’s use of light. More than 100 years after its completion, the building continues to inspire as a work of architecture and a place to make art. Its original architectural language is as fresh today as it was then. It is a symphony of light in many movements—a tone poem in north, south, and top light, with dark melancholic movements. Its organizational structure, based on well-proportioned studios, provides ideal spaces for teaching and making art and it has proven adaptable to changes in art practices and media.

The shock of seeing the Glasgow School of Art in flames on May 23 brought deep sadness and a sudden feeling of monumental loss. This building was and still is more than just crucial in the history of architecture. It stands as a breakthrough for modern architecture. Most importantly, it is a living and working place, deeply inspiring students.

The Glasgow School of Art embodies a refreshingly direct conviction: When you are working in a building that embodies great ideas, it lifts you above the misery of cynicism, gives you strength, and you can—if you persevere—find your own convictions and arrive at your own core values as an artist. The present intellectual climate in art and architecture could use any force it can muster against cynical reason and sarcasm.

The material and spatial energy of the building has just enough magnitude to present students with an ideal world in which to work and develop. This is why the building must be rebuilt and remain a school of art. Winston Churchill’s diction, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us,†has no greater example than the Glasgow School of Art, precisely because it has continued to produce students and launch them into the world every year since 1909. Therefore, we must all work rapidly for its complete restoration. We should challenge ourselves that only one year will be lost, and Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art will again launch students into the world in 2016. Georges Braque once said, “The only thing that matters in art is what cannot be explained.†The Glasgow School of Art has an inner worth and a dignity beyond all measurable value.

Restoration is Definite for Glasgow School of Art

By Hugh Pearman

June 6, 2014

“For me it began with a disquieting tweet from a Glasgow contact, around lunchtime on Friday, May 23. “Is the Art School on fire?†she asked. Yes, she confirmed when I urgently asked for information, it seemed to be gushing smoke. Then the photos and newsreel footage started to appear. It was looking worse and worse, especially when flames burst out of the top floor of the building. The horror from the world’s architecture community was real and immediate. Many, including me, were in tears. There is only one Art School in Glasgow: the one that is celebrated worldwide as Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s masterpiece. An extraordinary synthesis of Scottish Baronial, Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, and Japanese styles with industrial-modern construction methods, built in two phases from 1897 and 1909. Its interiors, especially its extraordinarily rich, timber-lined library with its purpose-designed furniture and fittings, also show the guiding hand of Mackintosh’s artist-designer wife Margaret MacDonald. This much-loved building was still in use exactly as designed.

All it took was an electrical explosion in a projector in the basement as the student degree shows were being prepared. Reports suggest that an installation using spray foam was nearby: highly flammable, it caught on fire, which then spread with terrifying rapidity through the voids of the building, from the bottom to the top. Attempts to quench it failed; staff and students had to evacuate and all did so safely. Well-drilled fire crews were on the scene in minutes, to find a growing inferno. They knew the importance of the building and its contents. Their task was to save as much as possible.

A week later, students and staff of the School of Art formed a guard of honour to salute those same fire crews as they finally left the building, led by a piper. What was still a cultural disaster of international proportions had also turned into something else: cautious optimism that the masterpiece could be restored. Yes, the jewel-like heart of the building—the library, only recently restored—had been destroyed. So had much else, including the extraordinary top-story ‘hen run,’ a glazed loggia that Mackintosh built to link the two halves of the building. But the worst fears of May 23—that the building would be completely gutted, might even have to be demolished—were allayed. The first phase of the building remains largely intact, thanks to the firefighters forming a 100-strong human chain on the main stair, successfully containing the blaze. Scotland’s fire service reported that 90 per cent of the building’s structure and 70 per cent of its contents had been saved, including its archive. But those reassuring statistics belied the devastation to the interiors simultaneously being shown in official photos. And the structural damage to the steel frame of the building has yet to be assessed.

The exterior of the newer western end of the building is now smoke blackened, especially poignant where the flames had burst through the multi-level metal-framed bay windows of the library. These were the inspiration for Steven Holl’s “driven voids of light†in his recently-opened extension across the street. That new building proved its worth in the aftermath when the school reopened and salvaged artifacts were laid out there for assessment and cataloguing. Holl and his partner Chris McVoy issued a statement describing the fire as “unbelievably tragic for architecture and the history of architecture. This is an unimaginably sad and deeply spiritual loss.â€

A similar sentiment was expressed by Stephen Hodder, president of the Royal Institute of British Architects. “Damage to a building of such immense significance and uniqueness is an international tragedy. It is irreplaceable,†he said. Nobody disagrees, and it is significant that both British and Scottish governments immediately pledged funds to help with the restoration. And with very few exceptions, full restoration is what architects of all persuasions are agreed on. As leading architect and academic Nigel Coates tweeted in the immediate aftermath, to widespread approval: “One of the most perfect interiors on the planet: the exquisite library at the Glasgow School of Art must be restored as was.â€

It hurts, of course, to discover that an advanced water-mist fire suppression system was in the process of being installed in the building. Work on this had reportedly commenced in 2013, and was due for completion this summer, but had been delayed by—supreme irony—the discovery of an older fire-protection material, asbestos, in the building’s foyer, which requires specialist removal techniques. Older-style fire-activated drenchersystems were not popular in historic buildings in the UK because of their visual intrusiveness and the water damage they caused to contents, especially if set off accidentally. And this, of course, was a building full of students.

Work is well under way to sift through the debris. Part of the damaged stone western gable of the building is being dismantled for conservation and rebuilding in collaboration with conservation agency Historic Scotland. And the school has launched a “fire fund†appeal to help with the reconstruction work. Terrible though it was, the fire at Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art has served to unite the world of architecture in a determination to save it.”

Hugh Pearman is architecture critic of The Sunday Times, London, and editor of the RIBA Journal.

http://archrecord.construction.com/news/2014/06/140606-Reconstruction-is-a-Definite-for-Glasgow-School-of-Art.asp