Wellington’s main (only?) central Railway Station has been getting a lot of press recently, mostly over the intransigence of the Heritage NZ lobby who are, to be honest, being silly over the heritage of this building. They’ve only just today approved the installation of a pedestrian ramp out the front doors – the disabled have been forced to use the side door for the last several decades. They’re sitting on the approval of installation of the Snapper ticketing terminals because they don’t like the colour. KiwiRail: do it anyway. It needs to be a living piece of heritage, adapting and changing to the times – not preserved in aspic (whatever aspic is).

The Wellington Railway Station is the newest version of a station on the site. Opened in 1937, it replaces the two previous timber stations on the site – the first one having been built way back in the 1880s (things moved fast back then – they dug the mainline rail tunnels on the Kapiti coast from Pukerua to Paekakariki way back in 1874). What should I call it? I can’t shorten it to WRS or it will just sound like a Subaru. Personally, I want to call it the Haubtbahnhoff, because that’s what every main rail station is called all over Germany, and this one certainly feels solid and Germanic.

It was designed by Gray Young Morton & Young and built by Fletchers and the skin is just a brick or so thick – so, maybe not quite as solid as it may seem. The plaque at the station indicates that in July 1994 it was the largest and busiest rail station in New Zealand – a record that is probably up for grabs these days. Certainly nowhere else in NZ has got 9 platforms (or, 9 and 3/4) but I think we’ve been beaten on the numbers by Auckland’s Britomart. They pump more passengers through each day now and once they complete the CRL they will rocket ahead even further.

Everyone has been going on about the outside this week, and yes, it does have a lovely outside, with that lovely row of Doric columns and the 30s style pediment. It’s serious, and clearly an important public building by its frontage, but the tan columns and brown brick facade still look welcoming and have just the right amount of imposingness. Being from the same era as Battersea Power Station, there’s something about the detailing of the brickwork that sings out to the world: “I am a child of the 30s!”

But inside it is arguably one of the weirdest, least successful railway stations of all time. Its not as weird and silly as Britomart in Auckland, where they tried to adopt the old Post Office into being a grand old station – but the Heritage people got in the way there too and so the floor was all weirdly up in the air. Possibly that has changed or is changing with the CRL – I honestly don’t know, as due to Covid, I no longer get to go up to Auckland much any more.

Anyway – where was I? Ah yes – just inside the front door, standing in the Great Hall, if we should call it that. I mean, it is rather tall and grand, isn’t it? There’s a coffered ceiling and an entrance to the Supermarket. But what happens in the Great Hall? Nothing much really, as it is really just a place to scurry through, on the way to somewhere else. So it is really more of a Great Vestibule, if truth be told. The Great Hall has some windows letting shafts of light inside and that vast coffered ceiling is very reminiscent of the grand McKim White design for Pennsylvania Station in New York: that’s right, the one that got away (demolished by horrid property developers in the 60s and regretted ever since). Incidentally, in Penn Station this is called the Waiting Room – but with nowhere to sit down and wait. More of a Meeting Room perhaps.

Next to the Great Hall is another hall, but this one is not very Great at all. Instead, it is rather low and human scaled, looking a little like an over-sized garden conservatory with a row of giant curved concrete arching beams holding it all up. Although a bit too pedestrian and mundane for my liking, this Small Hall is always bustling with activity, as it includes the Ticketing Office, the Information Office, a dry-cleaners, the all important public toilets, entry to a long ramp to the buses, the old Railway Cafe, and of course the direct link to the trains, as well as an entry/exit to the Supermarket.

This is the more traditional, European-style of “train station” – a lower roof, vast amounts of glazing, but of course one crucial difference of course – no trains in here. Here’s a picture of Hamburg Hauptbahnhoff – see any similarities? Not just the shape – its also the amount of commerce going on in the station in Germany. But for whatever reasons, Gray Young Morton & Young did not bring the trains inside as they do all over Europe.

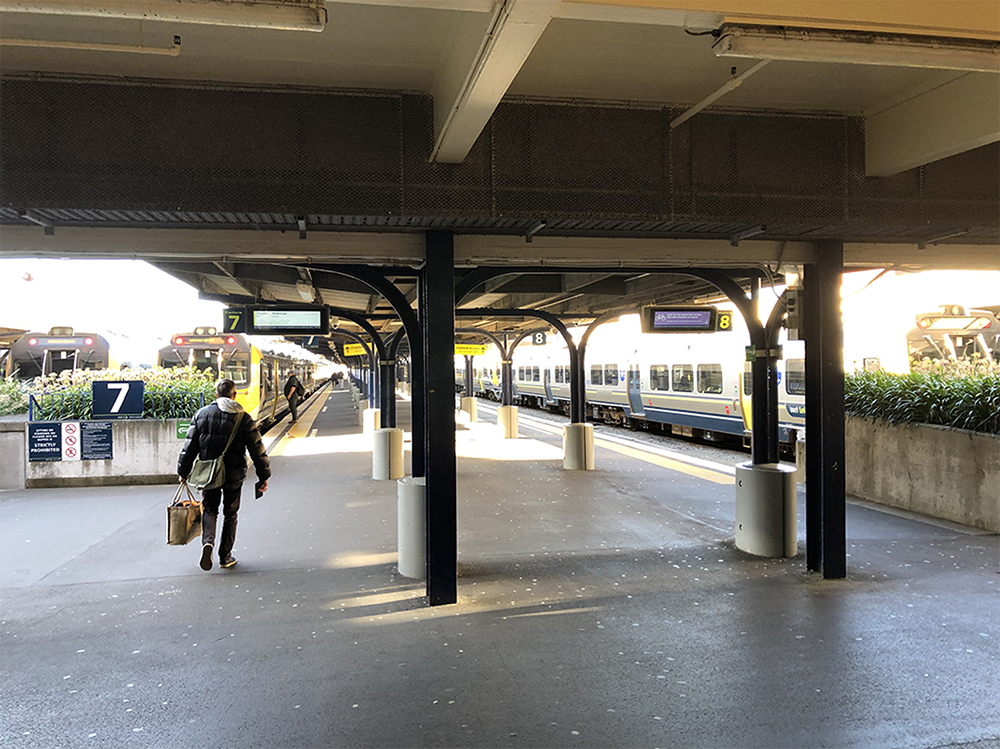

Instead, to catch a train you pass through to another area: the tracks themselves. In New Zealand, it appears to be the thing to do: to make the columns and roof structure out of old railway iron. I can’t recall other counties doing that – perhaps it is common practice. I’m not sure.

But let’s get back to the spaces themselves – the grandeur of Penn Station (gone) and of course the (thankfully still remaining) Grand Central Station in New York, which in the days of steam-powered locomotives looked like this:

Last time I was there I met my girlfriend at Grand Central – just to see if you really can do that (corny but true: people and long-distance lovers do indeed meet at the clock in the centre) – no great streaming shafts of light though, possibly because of the lack of steam locos these days… It’s still amazing, but the space feels different: not steamy and dusty, but still very busy. It’s a true urban meeting space – great bar down the far end, an Apple Store just behind you at this end, amazing ceiling mural of the signs of the Zodiac, and of course what feels like a million different train lines converging on this single space.

I know we do not have so many people in our Hauptbahnhoff, but still, there is a disappointing lack of action. These photos were taken last year just after lock down, hence not many people, and although I’ve tried a couple of times, it just feels dreadfully intrusive to take photos of the streaming hordes of commuters at peak rush hour when it really comes alive. Rushing in and out of the front door (below) the journey from the station takes you across a windswept plaza straight to the dubious duo of McDonalds and the Inland Revenue. Death and Taxes, right there at the doorstep.

Turning round and looking the other way, we can see that this Grand Hall is used for just a short passage of time. Blink and you’ve missed it. Which is a real shame.

The area where this shows the most is at the other end of the hall (opposite from the New World), shown in the picture below. Perhaps we should call it the Old World. Those doors used to lead into the Ticket Hall, with the NZR / KiwiRail offices above. There’s a lower ceiling height in the Ticket Hall to make it warmer and less draughty, but of course it hasn’t been a usable Ticket Hall for years, as WRS has become just a terminus for a suburban network and the original purpose of serving the whole of New Zealand has long since evaporated. Do trains even go any further north than Upper Hutt any more? Once or twice a day to Featherston perhaps, and if we’re lucky, once or twice a week to Auckland?

I used to feel a bit sorry for the Railway Station, thinking that they just simply could not get the tenants. There is just one sad, sorry, soulful, supplier of luggage – nobody buys any, as no-one is going on any long distance travelling from here. Perhaps a bag to carry the groceries.

But I realise now that it is probably not the fault of the building or of the KiwiRail owners. Getting right back to what I was thinking about at the very start of this exhaustingly long post, it is probably the fault of Heritage New Zealand. I’m sure that they have probably been putting their oar in, stopping any changes to the glazed frontages here, stopping any expansion of the retail areas, or the encouragement of more places to get a bite to eat. And shame on them for doing so. What the station needs is more: more trains, more people, more commerce, more life, more activity. It needs vitality – something is is sadly lacking.

I’m going to leave you all with a couple of pictures of the fantastic Hauptbahnhof in Berlin, constructed post-unification, with lines criss-crossing each other on multiple layers, most of them underground and consequently, under water. Outside it is a pure assembly of forms in steel and glass, but inside it is a riot of colour, of shopping, of escalators, encompassing the Underground, the Overground, long distance trains and nearby suburban routes. It is a piece of true heritage even if it is less than 20 years old – it is alive, which is what our station should be as well.

I expect there’s a mix of bad comms and general muppetry here.

Apparently Heritage NZ’s main beef was that it thought the ramp was too steep, which is weird as I thought the Council was the building regulator.

Either that or they’re on the side of breaching the Human Rights Act and the Building Act by limiting access to the (not very heritage, but still permitted) supermarket to only the able-bodied, and that wouldn’t be right.

Ramps should of course be on every building, heritage or not. Buildings are for people. All people.

Yes, it is a slightly tricky little place to roll out a disabled ramp – popping out between 2 of the columns and scooting down sideways. But if Heritage NZ are saying that was their only beef, they’re being disingenuous – have you seen the pictures of the Snapper outlets as proposed? They’re absolutely fine – obviously needs to be laid out in a manner that does not obstruct the mass of commuters entering and exiting the trains every day – and that’s the over-riding factor. The platforms are packed at rush hour – the last thing you want is to bash your groin on a steel post sticking up as you get swept along, so as far as I am concerned, they need to be brightly coloured and also quite tall and visible – with a banner/placard over 2m tall if possible.

The entire Wellington region has been hanging out for over a decade now, waiting for integrated ticketing. The ability to use Snapper on all buses has been great – now it is long overdue that we can use Snapper on trains and ferries as well. Auckland has been laughing at us and our inability to get our shit sorted on the ticketing front – we still have paper tickets and train conductors, while they have integrated Hop cards for years now. Time for Wellington to move forward and reclaim our place as the best public transport experience in NZ !

KiwiRail is rebuilding more of the SA carriages for the Capital Connection and GWRC wants to introduce more frequent service to Palmerston North and Masterton; and the Manawatu Regional Council wants more regional trains north and west of Palmerston.

Only thing I will say, hopefully we get a dedicated passenger operator in this country soon as KiwiRail seems to be only interested in tourist services.

I meant to say, the future of the station is looking up… hopefully

Every day trains run between Wellington and New Plymouth – is it so hard to clip a couple of carriages onto them? KiwiRail is evidently determined to maintain the compartmentalisation of train traffic into freight, tourism and (if you really insist) passengers. Perhaps they are waiting until all the station platforms capable of allowing people to get on board have been demolished.

There are no direct trains between Wellington-NP any more, in fact there is now only one daily return service to NP (from Palmy).

KiwiRail does not run very many freight services any more, let alone passenger ones…

Hmmm. I wonder where those trains passing through Whanganui are heading for?

“KiwiRail does not run very many freight services any more”.

That’s incorrect m28a31 – there are several freight trains every day passing along the Kapiti Coast and going down to Wellington. No idea where they are coming from (apart from, obviously, North), but the line seems quite busy to me.

Starkive: those trains on weekdays are to/from New Plymouth (1 return), Whareroa (2), Castlecliff (1) and Whanganui itself (1).

Alan: in addition to the Castlecliff trains above (the others terminate at Palmerston North), scheduled weekday return trips to/from Wellington are 2 to/from Palmerston North, 2 Karioi and 4 Auckland – plus, of course, the Capital Connection and the Northern Explorer.

But adding passenger cars to freight trains would be a real step back to the 30s (and beyond), and everyone would soon understand why that concept died out: the needs of freight and passengers are so different that in trying to meet both we’d meet neither.

Crikey! Was the Pukerua Bay to Paekakariki line really opened in the 1870s?

How come it still gets closed due to slips after about a century and a half?

As for Wellington Railway Station, won’t it need to be torn down when they extend the rail lines further south?

I’m certainly hoping not ! No, much as the Bus Station branches off to one side, I’m fairly sure that the next train line (fingers crossed) will be on the other side of the quay, and will be reached by a escalator up from Platform 9 and then another one down to the new Light Rail Platform 10 along Jervois Quay….

That’d be fantastic!

The line between Pukerua Bay and Paekakariki actually opened in 1886.

As for demolishing the station, I’m with nemo in hoping not – but I’m certainly hoping for a much more passenger-friendly arrangement than described, replacing a long unintuitive bus-connecting trudge to the west with a ditto light rail-connecting trudge to the east.

Every self-respecting Hauptbahnhof has a tram/light rail/bus terminal ideally located right in front of the station building. Instead, we have the trudge to the west, or, if you have the audacity to use the main entrance (soon, fingers crossed, with your wheelchair), you have to give way to cars as soon as you’re at the bottom of the steps, then a further two lanes to cross get to anywhere you want to go. It’s clear who the city is designed for, and it’s certainly not train passengers, or pedestrians!

I know better than to argue with you Betterbee, so I bow down to your superior knowledge on the subject of transport and trains in particular. But I could swear that I had read an article on Papers Past about a tunnelling accident on the Pukerua line in 1874. Just had another look and No, I can’t find it – but I did find this, from a letter to the Editor, showing that we’ve had this sort of person around for years:

THE WELLINGTON-WAIKANAE RAILWAY.

NEW ZEALAND TIMES, VOLUME XXXIII, ISSUE 5396, 13 JULY 1878, PAGE 3

“THE WELLINGTON-WAIKANAE RAILWAY. TO THE EDITOR OF THE NEW ZEALAND TIMES.

Sir, —The information recently given to the public in reference to a proposed line of railway to connect Wellington with Waikanae and the West Coast, was not very satisfactory to those who feel convinced that sooner or later such a line must be made. It appeared that, though no less than four lines had been surveyed or inspected, none was recommended by the engineers concerned in these preliminary surveys as likely to answer the required purpose. The only possible lines discovered seemed to be bad, and would require a large expenditure of money to carry a railway over any of them. I am surprised that no mention has hitherto (so far as I know) been made of a line which I believe to be quite practicable. Though not an engineer, I will venture to offer a suggestion. Assuming, then, that a line can be made somewhere from Wellington to the Halfway House, beyond Johusonville, a line might thence be taken to the Ferry, Porirua, and then on the south-west side of the harbor to Richards’ station, and across the harbor to Paremata, where the old barrack or,#e stood. Thence it might be taken round the coast to Pukerua, and under the Paripari hill to Paikakariki. From this last place it is known that no further difficulty exists.

From the ferry to Paremata is about three miles ; from that place to Pukerua six miles, and thence to Paikakaiiki throe miles. Twelve or thirteen miles would I think be the extreme distance. This line would be absolutely level the whole way. The only difficulty, if it were one, would be a bridge across the harbor at Paremata. No doubt four or five miles of the coast is rough, but I do not recollect that there is anything which an engineer would deem au obstacle or serious difficulty.

Will you be so good as to allow this suggestion to appear in your columns ?—I am, &c., W. !

July 5. P.S.—I think it not improbable that an easy line might be- found Inland from Paremata to Pukerua. The old path used – by Maoris was over some elevated land, but then they always gave the preference to such routes.”

I was a whole decade out ! Three Men Buried by a Fall of Earth.

THAMES STAR, VOLUME XVI, ISSUE 4999, 20 JANUARY 1885, PAGE 2

“Wellington, Last Night. An accident occurred about 4 o’clock this afternoon on the Wellington-Manawatu Railway Company’s works, at Pukerua, about 24 miles from the town, and which resulted in three men being buried underneath a fall of earth in a tunnel. It appears that twelve men were working in a tunnel in Mr Brown’s contract, when the timbers suddenly gave way, and a large quantity of earth fell. The nine managed to escape, but the other three were, when last reported to town, still entombed. Their names are Peter George, Henry Lloyd, and Matthew Panzadetti. The voice of the last named can be heard, and he states that he can hear one of the other unfortunate men groaning, but is unable to tell which. Dr Gillon has left in the Tui, and will be landed closo to the spot where the accident occurred.

Later, This day. Rescue of Two Victims Despaired of. The relief gang at Pukerua have un~ covered Panzadetti sufficiently to allow nourishment being given him. It is not expected that the other men will be rescued alive.”

The Pukerua Fatality,

EVENING POST, VOLUME XXIX, ISSUE 18, 22 JANUARY 1885, PAGE 2

“(From a Correspondent.) Paikakariki, Wednesday night. The second body was recovered to-night between 7 and 8 o’olook – that of Pietro De George, the Italian. The body was horribly disfigured, and death in his case must have been instantaneous. Nothing has yet been seen of the remains of the third man (Lloyd), although a drive has been put right through the slip. His body must therefore be lying nearer the walls of the tunnel, and cross drives will have to be put in. [Since the arrival of the foregoing, we learn that De George’s body arrived at Paikakariki in a boat this morning.]”

THE TUNNEL ACCIDENT.

NEW ZEALAND TIMES, VOLUME XLIV, ISSUE 7382, 23 JANUARY 1885, PAGE 2

“(from our own correspondent.) Pukerua, January 22, The body of Pietro George was recovered on Wednesday evening in a frightful condition, the corpse being flattened out to not more than an inch in thickness. It is said that while the rescuing party drove underneath the body, when engaged in getting it out, the pressure of the great weight lying on the unfortunate mao caused a constant dripping of blood on to the stuff below, rendering the task exceedingly unpleasant and ghastly. The third victim (Harry Lloyd) has not been reached up to time of writing.”

Note this bit: “the corpse being flattened out to not more than an inch in thickness” – Crikey! That’s gruesome!

Meanwhile, in Auckland, where entire populations are not being held up in fear of despoiling the Gods of Heritage, a brand new Rail Station has opened at Puhinui.

https://www.greaterauckland.org.nz/2021/07/26/puhinui-reopens/

This souvenir booklet published shortly after the railway station opened gives an interesting insight into how much more activity used to go on there; book-stalls, fruit-stalls, tobacconist, post office, barbers, waiting rooms (a ‘general’ one & a separate ladies-only one), bathing / washing facilities, three lounges for chillin’, a cafeteria, a restaurant, fenced rooftop play area for children and a nursery where trained nurses will look after young children while their mums take a breather.

https://wellington.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/4516

Oh John H – you wonderful person you! What an amazing find – thank you so much! I had no idea! That is an absolute godsend – the first few photos look like they were just taken yesterday, with hardly any changes to the outside, or the “Booking Hall” as they call it (I had wrongly called it the Great Hall) – all the more amazing in that you could once book tickets somewhere in there. But what really intrigues me is, where was the “Big Dining Hall” situated? I quote:

“This delightful room has marble walls, brightened by many mirrors. Pillars of marble have bronze bases and capitals. The seating is for 148 persons at thirty-nine tables. Breakfast on arrival of the Auckland express at 7.00am and the “Limited” at 9.30am and the steamer-express on week-days and Sundays.”

Presumably it was somewhere inside the guts of the building behind the ticket counters? (hence need for many mirrors). 39 tables is a fairly big ask !

Rest Rooms etc – I presume they were over on Platform 1, which has a lot of blanked off rooms etc still (from memory). And 5 luxury bathrooms, complete with a huge bath? Luxury! You don’t see many public bathrooms these days, particularly ones with actual baths in….

Wow, what a delightful time it must have been to travel by rail in the late 30’s …

IMHO the only thing really missing from Wellington station was a full width train shed that spanned all the platforms, removing the need for the rather rustic individual platform shelters…..

nemo, the Dining Room was what you’ve called the the Ticket Hall, a function that it served for just a few years after such dining ceased in the 1980s. And also on names, what you’ve called the Small Hall is actually the Concourse, a place considerably improved in recent(ish) years by the rather fine floor finish and the activity created by shoppers and students.

It would be nice to have a Hauptbahnhof like Berlin’s, but first you’ve got to find a suitable site for a brand new building in the city centre, and a population – and a travelling public – of many, many millions…

As for names, what’s wrong with Wellington Station?

And what you call intransigence, other people might call Heritage NZ doing its legally-required job.

In the mid 80s there was a cafe/restaurant behind the ticketing booths just to the right of them

Did good milkshakes

In the 1980s, nearly everywhere did good milkshakes. Its a rare find these days…

And then there was Kupe:

https://www.facebook.com/photosoldwellingtonregion/photos/a.868077186613887/755094661245474/

which bears an alarming superficial resemblance to this abomination:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/annedavid2012/25773717358/

Yes, I agree that the rugby statue is pretty plastic and grim – more of a soviet era chocolate box casting in mud, than anything inspiring to me. But – although I know some people disagree – I really like the statue of Kupe and the team – its a bit cheesy but it is also quite heroic. Far better in the bronze, outdoors, than it was in the plaster, cooped up in a railway station foyer too!

Lots of comments, thank you all. But interesting that none of you commented on the article itself. I thought I was uncovering some new finds (like, that the ceiling was based upon Penn Station, and that itself was based upon the Baths of Caracalla. Or is that all just boring and old hat? Already known? Nothing to see here?

I used to travel regularly from Auckland on the Silver Star sleeper in the 1970s – same price as the student standby air fare and steeped in euro-glamour and mystery (not least about what exactly it was that the buffet car cooks had drowned in white sauce this time). There was a zig zag corridor through the carriages to squeeze the sleeping compartments into the narrow gauge. But I have no strong memories of the station itself.

When I moved to Wellington a few years later, about the time the central city was at its nadir, the station was echoey and shabby – on its way to Detroit-style ruination – but still grand. The Booking Hall was functional in a bureaucratic way and the cafeteria was exactly that: closed at 3.00pm and a perfect setting for a Brief Encounter stiff upper farewell. It seems to me that outside commuter rushes the platforms were deserted and all the rolling stock were a dispirited red-lead colour.

The huge office warren upstairs was an indicator of how many clerical workers it took to run the railways – and how many Richard Prebble was able to scrap soon after. What on earth are those rooms filled with now?

I have been through a few real stations since those days, including Grand Central, but I think my favourite is LA’s Union Station.

https://www.discoverlosangeles.com/visit/union-station-the-story-of-an-la-icon

Thanks Starkive – some great recollection there! I remember going to Union Station as well in the 80s – when it was almost completely defunct – and it felt so weird that a major public venue like that had been so badly neglected. I believe that now it has been reborn and it looks alive again. There’s quite a bit of California rail up and down the state – less so the trans USA routes these days I think.

Re the offices upstairs from our Wellington Station, it is/was full of students last time i looked. Vic Uni had turned half of it into part of the School of Business for a while, when NZ Rail had moved all its staff to Takapuna in the most bizarre running of a company since Enron. Just for those that are unsure: there is no railway in Takapuna. There was some dodgy geezer called Michael Beard who proceeded to run the railways into the ground – i had a friend who worked there at the time, and the stories they used to tell me about the shenanigans then were amazingly sad. Since KiwiRail was then created a few years later, I think all the Takapuna staff have been moved back again – so possibly the upstairs rooms are once again full of Railway staff. From memory (unchecked, so I could be wrong, although no doubt Betterbee will know), NZR reached a peak of 38,500 employees strong before Prebble wielded his axe, one of the biggest departments in NZ. As most of the actual work is outsourced to other companies these days, the actual amount of official railway staff these days is tiny.

Re the offices, YooBee and its students occupy the western end of the building, and KiwiRail the eastern end, which has RAILWAY OFFICES proudly over the entrance. TranzRail (NZ Rail was history by then) did move some – but by no means all – of its staff to Takapuna on the principle espoused by Mr Beard that a company should be near its customers rather than its operations, emphasised by his desire to outsource much of the latter, which was never achieved.

The railway office end has always been pretty well occupied, and there has been no general movement of staff back from Takapuna – but that office has now moved to central Auckland, right beside the railway.

As for the number of staff, I thought that the maximum number was around 25,000, but that may have been just a figure that was bandied about.

And “most of the actual work is outsourced to other companies these days”? KiwiRail staff run, crew, control and maintain its trains, ferries and tracks (with some outside help, of course), so what the “actual work” is that is being outsourced is a bit of a mystery to me.

Favourite stations? Mine are two, the adjacent St Pancras and King’s Cross in London. The former is gloriously elaborate, the street frontage a triumph of decoration over functionality (though concealing the engineering triumph of the train shed behind, built on foundations that reflect the dimensions of barrels of Burton beer, a primary traffic); the latter dourly functional, its structure exposed to the world. The 21st century (at least pre-covid) has seen them both flourish, both buildings simultaneously returning to their origins while adapting to and thriving in and meting the needs of the modern world.

Thanks Betterbee. Yes, I agree that Kings Cross and St Pancras are both lovely – each so different from the other. I never got to stay at the newly revitalised St Pancras hotel – apparently it is amazing. I only got to see the old hotel when it was a pigeon-strewn ruin.

Re the outsourcing of functions that used to be NZR, isn’t there Transdev, and Ontrack, and TranzMetro, and AT, all doing work that NZR formerly would have done itself – and then Downers etc doing the actual work for the bits that are still KiwiRail? For instance, all the crews i see that work on the lines have Downers jackets on, not KiwiRail.

Thanks, nemo. Downer staff working on KiwiRail is an example of the “outside help” that I referred to, working alongside KiwiRail’s own track staff on particular projects. Consultants and contractors are everywhere in every business!

Agreed that KiwiRail is a lot smaller than NZR was in its heyday, but that’s mostly through divestment rather than outsourcing. It’s AT and GWRC, not KR, that outsource to Transdev: KR’s interest in those services is as a supplier rather than as a principal. I’m dredging back into my memory here so the details may not be precisely right, but responsibility for those operations was transferred to regional authorities in the 1990s, and whichever of KR/Toll/TranzRail was the rail operator at the relevant times declined to quote for the Auckland metro contract and failed to win the Wellington one. (Similar divestment took place earlier when InterCity and Cityline buses were separated from the rail and ferry operations of NZR.)

There hasn’t been any significant divestment since KR was created in 2008 from ONTRACK and Toll’s rail and ferry interests.

Incidentally, going back to the original piece, a further comment: “it replaces the two previous timber stations on the site” is not quite right. It did replace two timber stations, but one of them (the one serving the Main Trunk) was halfway up Thorndon Quay, about where the current depot is, behind the office block at no. 204.

Fascinating stuff about the 1885 tunnel accident, and a railway following the coast northwards from Plimmerton would have saved a lot of tunnelling and made eliminating the remaining single-track bottleneck easier, but I doubt if it would have been as straightforward as Mr W.I. seemed to think. There will always be armchair experts who know best!

Just for the record, the DomPost today published a bit more about the back storey around the ramp access:

https://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/wellington/126129801/heritage-nz-had-concerns-about-railings-shape-of-wheelchair-ramp-at-railway-station

“Heritage New Zealand advisors were concerned the colour and shape of a wheelchair ramp at Wellington Railway Station would clash with the building’s architecture, emails acquired under the Official Information Act show. Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga agreed in July to support a ramp being built at the front of the station, after a more than two year dispute with KiwiRail over its design. The Wellington station is owned by KiwiRail, but is a Category 1 heritage-listed building regulated by a covenant, under which Heritage NZ must agree on significant changes. Architect David Donohue provided an initial concept design to the agency in June 2019, a black ramp on the left side of the main entrance with sharp turning sides.”

“Heritage advisor Laura Kellaway responded suggesting “a very transparent scheme with as little handrail as possible” and that the handrail would be “preferred as old bronze in period style”.

In internal emails from October 2019, Heritage staff debated whether the ramp would be intrusive on the building’s design. “To me, it does seem quite obtrusive, and it’s a shame it affects the symmetry of the grand entrance so much,” one staff member wrote.”

For readers of the Fish in later years, I’ve got to say that I totally agree with heritage advisor Laura Kellaway – the black ramp looked terrible and the new proposal with a curved handrail in period bronze looks so much better. Yes, it will of course cost considerably more, but surely it is worth it with NZ’s category 1 heritage. The real issue is, why did it take 2 years to get to this point?