A group fighting to keep the Gordon Wilson Flats from being demolished, despite the building having sat empty for years, has come up with a bold new plan – one that includes a cable car.

The Architectural Centre – a group which successfully appealed to the Environment Court to keep the building on the heritage list in 2017 – shared its vision for the site, including the neighbouring McLean Flats….

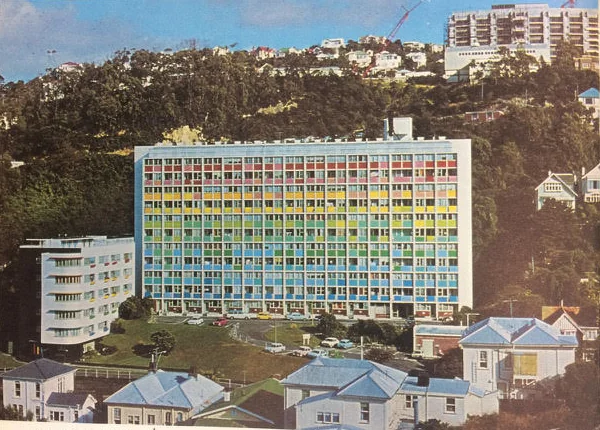

It is wonderful to see the Architectural Centre spring back into life with a proposal like this, and positively add to the conversation with a reposte to the Post, who insist on calling the Gordon Wilson Flats a “derelict eyesore”.

It’s only an eyesore because of the graffiti taggers and vandals who have been allowed to roam freely around the building for the last decade and it is only derelict because nobody did any maintenance to the building for several decades. The building is actually still in reasonable structural condition, with the exception of the (easily replaceable) external concrete panels on the balconies, which could be simply replaced with new panels that look the same, made of materials that do not corrode.

The building looks scungey because the concrete cancer has eaten into the panels, and because wankers with spray cans have added their weird hieroglyphics to the walls – but guess what? That is all easily fixable! New panels, new paint, new people, new future!

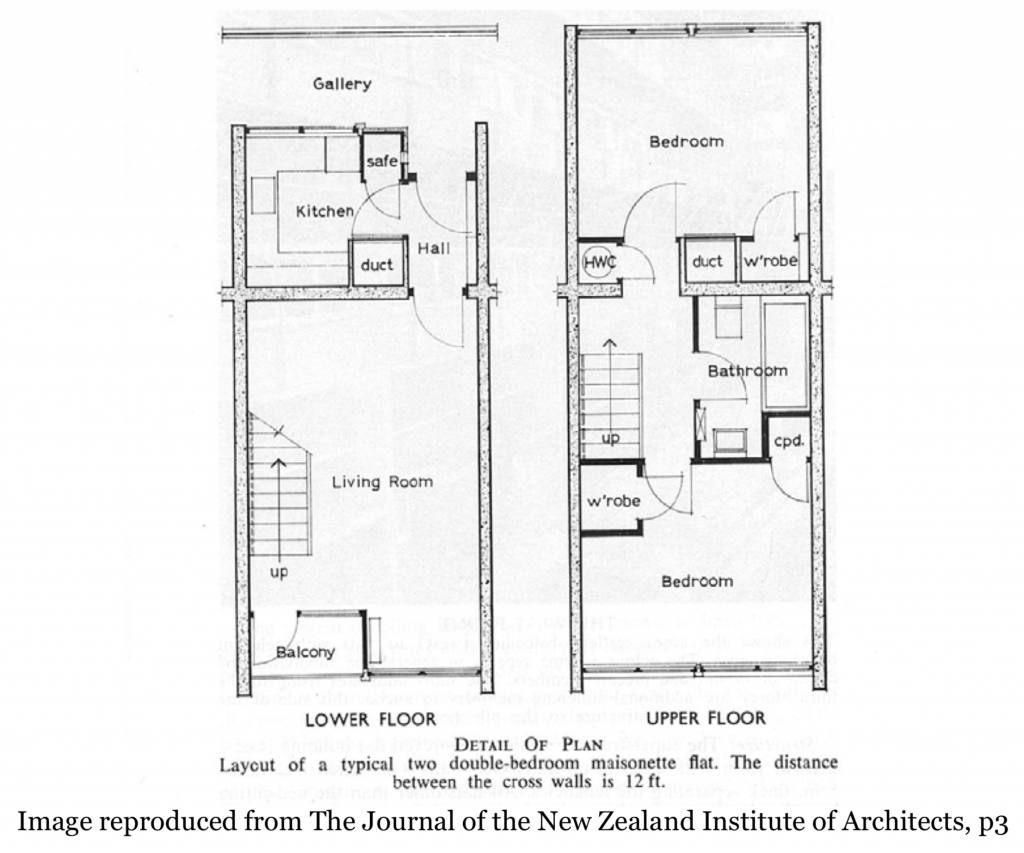

Let’s recap a little. The Gordon Wilson flats, named after the brilliant architect in charge of the Housing Division at the Ministry of Works, were created as housing for people post war, has a clever design with two-storey high maisonette flats. With the building being aligned north-south, the flats get fantastic sunlight and daylight from both the east side and the west side. Most flats in NZ are just single-sided, and are boring, suffering from bad air and bad light. At the GWF, there are access corridors on the west side every two storeys, which means that the other floor faces both ways – and gets great air and great sunlight as a result. More info here, from docomomo.

It is, architecturally, far superior to almost every other apartment building in New Zealand – there used to be another in Auckland, but they knocked it down recently, so this really is the only one like it in the country. Worth keeping? I think so.

The building was the subject of research by Auckland-based architect Ken Davis many years ago (Davis, Ken. “’A Liberal Turn of Mind’ – The Architectural Work of F. Gordon Wilson – 1936-1959 – A Cultural Analysis.” Victoria University of Wellington, 1987), and so it is lovely to see that Ken has returned to the subject, and appears to be one of the architects behind the new proposal. The proposal retains the apartments as housing, which presumably could be for students or rented out to the private sector – either way, it goes a good way towards providing much needed housing for the city. It also copes with the “want” of the university to have a “new front door” to the city, by situating a new timber building down near the road and connects with the existing Uni up the hill by means of a cable car – a boon for all those tired student legs who are exhausted climbing up the hill. This achieves much the same outcome as the University had proposed before (below).

The main reason that the GWF are not occupied is because of the egomaniacal plans of the former Vice Chancellor of Victoria University who oversaw the loss of millions of dollars from the University’s budget while he was in power. By all accounts, no one at the University liked him, or his stupid campaign to re-name Victoria as the University of Wellington, and no one missed him when he moved on and went wherever old vets go when they retire.

Post-Script: A load more information on the GWF, courtesy of the docomomo paper on the building:

The Gordon Wilson Flats were built in a second wave of medium- and high-density state rental flats, coming after the six blocks built by the first Labour Government in the period 1935 to 1949. The first of the state’s higher density developments was the two- and three-storey Centennial Flats in Berhampore, Wellington (1939-40). These were followed by the Dixon Street Flats (1940-44), McLean Flats (1943-44) and Hanson Street Flats (1943-44), all in Wellington, and the Greys Avenue Flats and Symonds Street Flats (both 1945-47) in Auckland. All six buildings are important milestones in the development of New Zealand’s modern architecture. They were followed in the mid-to-late 1950s by the Gordon Wilson Flats and the Upper Greys Avenue Flats (completed 1958) in Auckland.

Chronology

commission or competition date: 1943 indicative designs / 1952 subdivision of site approved / 1954 tower block commissioned

design period(s): 1943 concept sketch / July-August 1954 working drawings

start of site work: 1956 / Honourable Dean J. Eyre, as Minister for Housing, laid the foundation stone on 6 August 19573

completion/inauguration: early 1959. The Flats were named after Government Architect F Gordon Wilson, who died suddenly on 23 February 1959 during the late stages of construction.

commission brief: Following its election to power in 1935, New Zealand’s first Labour Government

established a Department of Housing Construction to develop state rental housing schemes throughout the country. This was in response to a severe nationwide shortage of housing, especially in the urban centres of Auckland and Wellington, which accounted for 80% of shortfall.

The state’s housing schemes were largely intended to provide single-storey, detached housing in the outer suburbs of cities. However, F Gordon Wilson, chief architect of the Department of Housing Construction, and John A Lee, the Minister of Housing, agreed that there were distinct advantages to including multi-unit blocks of flats in the innercity areas of both Auckland and Wellington.

The large and rapid population growth of Wellington in the early 1940s was caused by the influx of labour into the capital to work in essential industries associated with World War II. The extreme housing shortage that resulted has been described thus: ‘At Wellington, where sites were limited, building costs were high and where government employees had multiplied rapidly during the past few years, the demand was particularly strong’. The provision of state housing on the periphery of the city to meet this housing shortage was contributing to the city’s urban sprawl. To assist in mitigating this effect, the Department of Housing Construction developed state rental housing schemes for Wellington’s inner-city.

The building is constructed from reinforced concrete and structural steel. 200 mm concrete walls and 135mm concrete floors separate each of the two-storey maisonette flats, with timber intermediary floors. The flats’ innovative foundation system, with piling down to the bedrock, had not been done before in New Zealand.

technical evaluation: The Gordon Wilson Flats are of significant technical value for their reinforced concrete construction and unique piling system. Piles at the outer edges were bored to 6 metres, with central piles deeper at 14.5 metres. Reinforced bored pile holes were filled with a dry-mix concrete aggregate before a fluid grout mixture was injected and then left to set over a period of several months; this method of piling to the bedrock had not been done in New Zealand previously.

social evaluation: The Gordon Wilson Flats are of social significance as the last high-rise block of state rental housing built in New Zealand. The building was commissioned by the first National Government (elected in 1949) and became its most significant high-rise social housing project, in tandem with the Upper Greys Avenue Flats in Auckland.

The first tenants who moved in during 1959 were generally positive about their experience, appreciating the views afforded from the higher floors. There were complaints, however, that the view was lost once you sat down as the windows were placed too high. Other complaints included the lack of space in the kitchen to accommodate a fridge and personal washing machine and the communal rubbish ducting system. The innovative hot water system powered by gas was a continuing source of complaints and, after ten years, it was replaced.

Plug the eco-angle

“Recycling is the sustainable way and in these cash-strapped times it makes sense to crane off the offending panels and redo the flats on top of their good bones”

“Anyone who is against this idea is obviously pro-global warming” all that kind of horseshit

She’s got a face like a dropped trifle so appealing to guilt is a better approach than aesthetics

Best of luck to them, it would be a waste to knock it down then build essentially the same thing

Or maybe Simeon has designs on the site as a vent for his long tunnel?

Great post. It seems a shame to waste a re-usable building. Have the University released their own housing scheme to replace it and will it take them another 10 years to do so?

If this design was built today, from the ground up, with all its features (2 levels, noth-south, etc) each unit would probably sell for a fortune. In fact, if the finishings were such its probably an easy sell as luxury weekend bolt-holes or Air BnBs for people visiting their kids at The University Of Wellington (I did prefer it…)

And then there is the whole housing shortage thing.

Such a waste.

You published a floor plan a while ago. As I remember, the floor plans seemed quite dated in the 21st century, and I suspect that it wouldn’t be possible to change them much.

Probably all right for a couple of nights, but not long term.

But hey – hands up all those who’d buy one of these to live in – how many votes’d we get d’you reckon?

Thanks Mr Filth – I’ve inserted those plans here in this blog-post here as well, if you scroll up. Are they dated? Well, upstairs, the two bedroom layout is still much the same, but the bathroom would probably be updated with a shower rather than a bath. Downstairs, the kitchen in a separate room is definitely dated, but actually it is still highly functional – and the important thing to not is that No, it could not be improved by taking out the intervening wall – that’s an important structural wall keeping the building up, so needs to stay. But apart from that, this “maisonette flat” is almost exactly the same as the “townhouse” designs going up all over NZ at present. Would I buy one? Hell yeah!

Structural wall indeed! Just you wait until twenty or forty have been converted to “nearly-semi-open-plan” by knocking out that wall and replacing it with an (engineer-approved) steel beam.

Interesting to see the amount of storage, too – designed for 1950s levels of “stuff”.

Ha !! I think that if they did take out those walls, then it really WOULD be an Earthquake Risk…

The Earthquake Risk thing is obviously the biggest thing – not the appearance on the outside, which is a Red Herring – but in reality it is the method of pouring the foundations that has people running scared – this bit here:

“Reinforced bored pile holes were filled with a dry-mix concrete aggregate before a fluid grout mixture was injected and then left to set over a period of several months; this method of piling to the bedrock had not been done in New Zealand previously.”

So the issue is that no one quite knows the strength of the concrete down at the bottom of the foundations. But: do we ever know that?

I’m with you. Great city views also. Inspired by my father Nigel Cook, I spent years walking & cycling round London & Birmingham looking at council flats and talking with him about designs. These are excellent flats and pulling them down is a bizarre decision in a housing crisis.

[…] Eye of the Fish: https://eyeofthefish.org/last-ditch-bid-to-save-fantastic-modernist-building/ […]

I am disturbed that VUW purchased the building with the intention of demolition. They knew when they purchased it that it had a Heritage listing. It wasn’t imposed unfairly on them.

I find it extraordinary that they would spend $60+ m on a zero carbon Living Challenge Living Pa yet concurrently do their darndest to send Gordon Wilson flat’s embodied carbonto the landfill. VUW have willfully allowed the Gordon Wilson flats to degrade for a decade and yet concurrently spent money to try to progress the demolition.

Its also distressing that Wellington, and VUW’s students, need building like this that provide well designed residential accommodation.

A few weeks ago I received in the mail an appeal to Alumni to donate. FFS.

Our point exactly Stuart

Stuart – it should be noted that “VUW” does not think with one brain, and as it has several thousand staff, it clearly harbours multiple different viewpoints. To that end therefore, I think it is safe to say that, from what i understand in discussions with various staff members there, that many of these decisions were made by a previous Vice Chancellor, and do not represent the views of the majority of the staff. He was disliked by many (allegedly), made many woefully inept decisions (allegedly), got the university into a massive amount of debt (allegedly) through bad luck and / or incompetence (allegedly) / wilful mis-management (allegedly), and then left under a cloud. Allegedly. The VUW you see today is not the VUW it was then, or so it seems.

Nemo – The current VC has made no moves to reverse their course of action. Rather they have been actively lobbying to have the GWF removed from the WCC Heritage Schedule. Mayor Whanau is reported as saying that leaving the building on the heritage schedule is ‘..not what the university want. Thats why we’re going to continue looking for an alternative route to get that de-listed’.

So you can blame the previous VC but the current one has shown no signs of enlightenment.

Looking at all his decisions here, just about the best possible outcome?

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/chris-bishop-makes-way-for-more-housing-in-wellington-but-keeps-controversial-heritage-listings/5WLZA3NMBZGUBBTCABMTW4XWYY/

The Official statement is here ,

Picking off Heritage buildings that council didn’t like ( or owners wanted to change) never seemed to be an appropriate use of the DP process.

I also think that the Minister was sending the council a bit of a coded message, of “i’m not gonna just roll over and give you every thing you want”

https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/decisions-wellington-city-council%E2%80%99s-district-plan

https://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2024-05/Attachment%20A%20WCC%20IPI.pdf

Speaking of resurrecting things, this looks familiar

https://www.stuff.co.nz/home-property/350288727/couple-turn-old-public-pool-award-winning-home

Word on the street (ahem) is that there might be some progress on the GWF saga. Anybody closer to ground zero able to expand on this?