Sad news, but not entirely unexpected. Friedrich (Fritz) Eisenhofer has passed away, at the splendid ripe old age of 96. NZIA has sent out a small note of his funeral, but to be honest he deserves a bloody great big obituary – and probably a book as well – and I’m probably not the person to do this. Many of you will have known him better than me – I only met him once or twice.

NZIA says:

“A memorial service to celebrate the exceptional life of Friedrich (Fritz) Eisenhofer will be held on Wednesday August 16 at 11am, Cedarwood, Parata Street, Waikanae. The modernist architect was 96 years old when passed away at the idiosyncratic, sustainable home in the sand dunes of Peka Peka that he created with his wife Helen.”

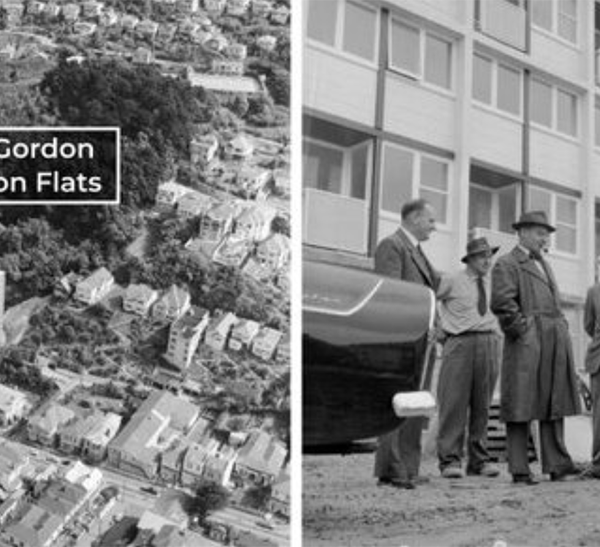

“Fritz, a Fellow of Te Kāhui Whaihanga, trained at the Kunstakademie in Vienna, and came to New Zealand Aotearoa via Australia in the 1950s. He worked in the Housing Division of the Ministry of Works before establishing his own architecture practice in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.”

There is of course so much more to say than that. Eisenhofer was one of those rare architects that Wellington people refer to by name – single name of course – and one of the last of the true Modernists. They literally don’t make them like that any more. Incidentally, as far as I can tell, the name Eisenhofer means something cold and hard and made of Iron, made of Hope. Wikipedia notes that he was born in Austria in 1926 in a small town called Spittal an der Drau (a name which curiously translates as Outside at the Hospital). Like most good Austrians he studied at the Kunstakademie in Vienna, and then he decided to emigrate to New Zealand after the Second World War, arriving in 1953 when he was just 27.

Fritz started off working in NZ with the Austrian tradesmen who were building the first 500 state houses at Titahi Bay, which is one of the great precursors to the pre-fab housing boom that is ongoing now. After that he began working at the Department of Housing, and later in the 1950s he teamed up with another Austrian, Erwin Winkler, in an office sandwiched between the CubaCade (now the Left Bank) and the Matterhorn Swiss icecream cafe. Well, of course !!

Although the more official accounts may not mention this, Fritz was a bit of a looker – stunning good looks and his sexy Austrian accent saw him marry his gorgeous wife Helen, who was the winner of Miss Wellington or some such swimsuit competition. They were a good looking party couple, staying together till the end. I suspect he probably looked good in a pair of Speedos as well – they were both sun-loving naturists. I think I saw him when he was about 91 and he was still a beautiful man, bronzed, bald, but in good health, still with a good Arnie Schwarzenegger accent, even after all these years. Incredibly he stayed home until he passed away.

Eisenhofer was a staunch Modernist, and his houses show that. Well, at least some of them do. He designed the famous Coffee Bar for Suzy – which really started off the whole crazy coffee culture for NZ and especially for Wellington.

Please write in and tell me if you have more info to hand – it was all long before my time here. Eisenhofer houses are special, even today.

I’ve got to find Julia Gatley’s book on Wellington architects – and probably Geoff Mew’s book as well.

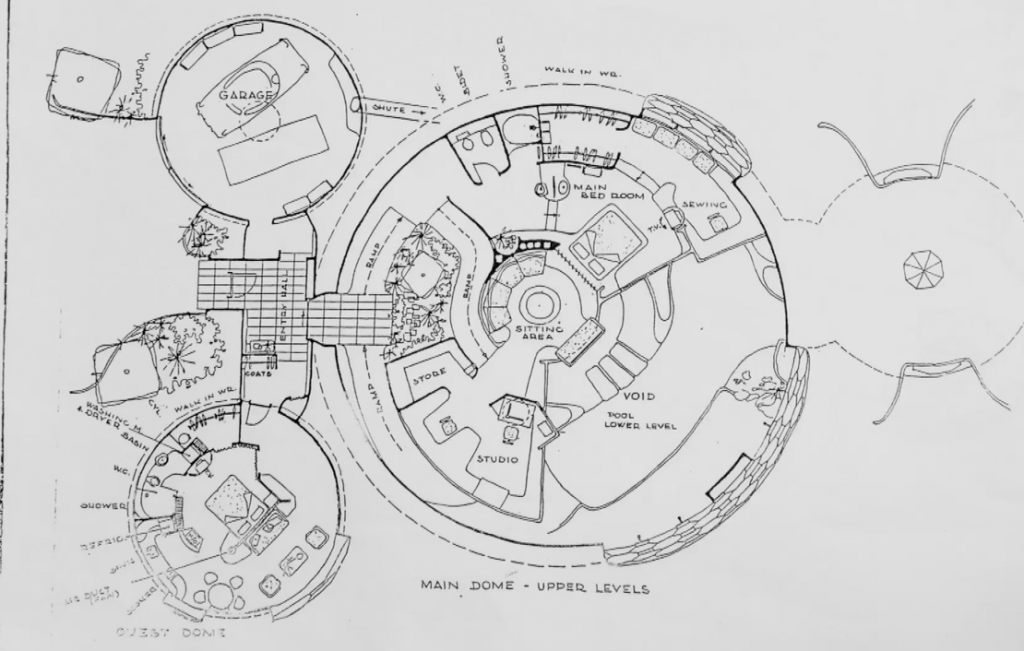

It is likely that he will be forever known best by the house he designed for himself and his wife – a dome house set into the sand dunes up at Pekapeka. As architects are want to do, he designed himself something a little special, that he probably could not persuade a client to do. Although, so saying, he designed the house next door as well, which while not a complete dome, was also a sculptural wonder.

I’m searching for my photos of his house and the neighbour’s house – they were special. Think Batman’s secret lair, but a version for when he had retired on a sunny coastline. White, not black, but just as cool.

Amazingly the shell itself was a very thin skin of concrete – according to the film, only 35-50mm thick. Well insulated, and facing towards the sun, it is probably one of the reasons he lived so long – no chilly winter breezes in here.

There was an indoor pool, and an outdoor pool, and native plants in both – and forgive me that I did not go for a dip when I was there – but I think that you could swim from inside to outside. The plan was a series of bubbles, as the whole thing was a collection of domes, and glazing was – of course – a series of hexagonal panes.

Rest in Peace, Fritz. There is not going to be another like you.

Post-script

The NZIA have published more information online, and some of this is reproduced below:

Aotearoa New Zealand was home to Austrian-born Fritz Eisenhofer for 70 years and during that time he was instrumental in introducing modernist design principles to residential architecture. In blurring thresholds, opening up spaces, incorporating nature and increasing natural light and connectivity, his modernist ethos was the antithesis of the typical New Zealand domestic setting of the time. In 2010, Fritz was named an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to architecture. “Fritz Eisenhofer was remarkable for the length of his career, the number and range of his works and, more importantly, for his ability to change, reinvent and continuously progress his design practice,” says Dr Tanja Poppelreuter, Associate Professor Architectural Humanities at the University of Salford, England, and author of ‘Changing places: New Zealand Houses by Winkler & Eisenhofer 1958 to 1969’, which was published in The Journal of Architecture in 2013.

Fritz was born in 1926 and trained as an engineer before studying architecture at the Kunstakademie in Vienna. In 1953, in the latter half of his twenties, he travelled to Aotearoa with a group of 194 Austrian tradesmen. In the midst of a labour and housing shortage here, the group was contracted to build 500 state homes in Titahi Bay, Porirua, from pre-cut larch imported from their home country. Following the project’s completion, some of the group decided to stay – Fritz was one of them. He gained residency and took a job with the Department of Housing in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, where he noted the forward-thinking designs of government architects.

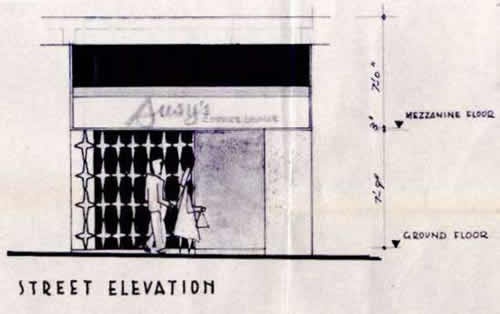

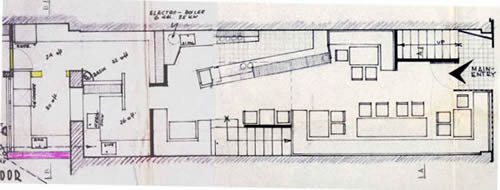

In 1958, Fritz and fellow Austrian architect Erwin Winkler established a practice, with their studio at 108 Cuba Street, Te Whanganui-a-Tara. The first private home they designed was in Takapu Road, Tawa, and many others followed that expressed individuality and an international modernist style. Winkler & Eisenhofer was active until 1969 and notable examples of their work can be found in Karori, Lower Hutt and Khandallah, including the multi-level house on Rama Crescent with a swimming pool and courtyard that Fritz designed for his family. The designs were reminiscent of the glamorous modern aesthetic seen in the Case Study houses built in California between 1944 and 1966, says Tanja. “Their commissions were so numerous and so uncompromisingly modern that Winkler & Eisenhofer belonged with the main contributors and developers of mid-century modern architecture in New Zealand.” There were other commissions, including designs for Chez Lilly restaurant, the showroom for Viking Records and, in 1964, the sleek and stylish interior for Suzy’s Coffee Lounge in Willis Street. After 23 years in business, the cafe became a landmark and is the subject of the Rita Angus painting ‘At Suzy’s Coffee Lounge’ (1967, Te Papa).

After the practice dissolved, Eisenhofer designed Whenua Tapu Crematorium, Porirua, and his internationally regarded dome home in the sand dunes at Peka Peka beach. “In a 2010 interview he told me how this house arose from a long-standing interest of building with the landscape and utilising the earth around it,” says Tanja. “He attended conferences and was active within earth-building communities before designing this house that amalgamates with its surroundings and spans over several levels without stairs. The ambience of individual spaces is that of separate, individual ones but they in fact merge and flow seamlessly into each other to form one interior space.” The Peka Peka house was his most experimental, and probably most personal, project and he lived there with his wife Helen until he died at 96 years old. Building the home’s four concrete domes, which were dug deep into the earth, was a labour-intensive project that began in the late 1980s and took four years to complete. In a 2010 interview on Saturday Morning with Kim Hill he said of his career and the home: “You always try to extend the boundaries”, “You progress”, “You experiment”, acknowledging that getting consent for the idiosyncratic, eco-centric design was easy at the time, but would now be “almost impossible”.

John Walsh and Patrick Reynolds included the dwelling in their book Home Work: NZ Architects Own Houses (Random House), and it has been covered in local and international publications. In a feature by The Guardian, an interior photo shows Eero Saarinen Tulip chairs beside the indoor pool – a setting that could been a scene from a Hollywood Hills home. By contrast, from the outside the partially submerged home is both an oddity and a wonder embedded into the rugged coastal landscape.

Starkive – I’m guessing that you would have had contact with Fritz over the years? Any stories to tell ?

Sorry to say I never met Fritz – though he was evidently a cool cat. I have been through two or three of his houses and nearly bought one I believe is his – the one with the zigzag front pavilion on the coast road to Kilibirnie. I love the idea – though perhaps not the humid reality – of the dune house.

On the whole, we did pretty well out of Austria didn’t we?

The video referred to above can be found at:

https://www.archdaily.com/126746/video-a-dome-in-peka-peka-fritz-eisenhofer

His indoor pool ran foul of the pool fence laws when they were updated,

https://www.building.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/resolving-problems/determinations/2018/2018-017.pdf

Not sure what the final solution was

That’s amazing ! I had a determination once – and the result was that I won, but that the Authority made it all very Non Person Specific. This one seems openly harsh and vindictive – named them, and included a picture that is clearly of their house. It is ironic, as they are near the sea, which is of course larger, and very unfenced, and a much larger hazard. But MBIE are not threatening to sue God, as far as I know.

Re the final solution: pretty sure that the Eisenhofers told MBIE to stick their Determination up where the sun does not shine. (by that, I clearly mean the rock storage bin below ground, which retains the solar energy).

I’ve lost the link but there was a joker building at leat one place down Seatoun way with this thermal rock idea except his one was more like the rocks were trapped in an insulated basement and slowly heated up over almost a year

Eisenhofers rock heat storage system I had heard about a long time back and always thought it was brilliant

Also is it subconscious that people use the term ‘final solution’ when talking about Austrians or am I too sensitive?

Enjoyed this, particularly as there are numerous ponds as well as the sea close by. This was a very trying for us trying to fight a large government department….anyway a solution was found eventually

Fritz would have enjoyed this obituary!

Lovely to see you here Helen – thank you for your comments. I’m sorry for your loss – sending my warmest regards. I’m interested to know – did he ever publish a book on his work? Or has anyone written about him? (maybe there might have been a student thesis or two, perhaps?). I feel that there is probably more on the Eisenhofer saga than I have found so far – he was very well known, so I am sure that there must be some wonderful tales to be told? If there are any stories about the wonderful life that you and Fritz had together that you would like to share, we would be happy to help publicise them.

Thank you, yes there are many fascinating stories I could tell especially now as my mind has been travelling back in time and I realise we lived through an amazing era and Fritz did a huge amount of work. There has been an academic paper published about the work the partnership did in the fifties and sixties, newspaper articles but no book. Yes I would be delighted to share my recollections with you while I still have a relatively sharp mind and my memory bank is still active

There was a big book written on Fritzes work in Europe I believe. But not published in English.

Nothing coming up on a search of Amazon.de – I’ll try my German spies in Deutscheland and see what they can come up with.

I’ve only been to Austria a couple of times, but it was lovely, out in the country. Very much like Wanaka, in a way, only with more deciduous forests. Great fish dish for lunch – trout, fresh from the lake, grilled, mit kartofle und case…. i could see how Fritz would have felt at home in NZ. Similarly unspoilt country back then, perhaps? He would have only been 13 when WW2 broke out, and just 19 when it finished?

Vienna, of course, would have been about the furthest away from NZ, culturally, as you could get back then. Wein: intensely urban, and urbane, frauleins with fox furs overcoats and cafes everywhere, immense wealth in the old families, aristocratic hierachies still in place – vs Wellington and the Hutt which would have all closed up each night at 5pm on the dot and gone home to the suburbs, not a cafe in sight, nor much of a restaurant scene, just a boozer with the 6 o’clock swill – that would have been a rude awakening to a young Austrian sophisticate back then !

You have the picture! On our last trip to Europe in 2018 we spent time in Vienna and walked everywhere, so glad we visited often as our son Graeme and his wife and daughter live in Dresden where he is a Professor at the medical University since 2008, having previously been working in Bethesda Maryland at the National Institutes of Health where he had been since 1985.

As far as I am aware it was an academic paper published and very well researched in Europe by a Lovely German born lady who married a New Zealander and worked at the Auckland school Architecture. I believe she is working at a University in England. She also did a doco which is available on YouTube. There have of course been newspaper articles and magazine articles in both Britain and the Netherlands in Dutch.

Judging by the info in the excerpt fro the NZIA info above, it sounds like that may be:

Dr Tanja Poppelreuter, Associate Professor Architectural Humanities at the University of Salford, England, and author of ‘Changing places: New Zealand Houses by Winkler & Eisenhofer 1958 to 1969’, which was published in The Journal of Architecture in 2013.

Link to the paper :

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13602365.2013.859167

Just adding to the information about Fritz’s passing, here is the article from Architecture Now:

https://architecturenow.co.nz/articles/vale-friedrich-fritz-eisenhofer/

It notes that: “Friedrich ‘Fritz’ Eisenhofer was a renowned modernist architect, considered by many to be visionary in his use of solar gain, sustainable design principles and building relationships to the surrounding landscape. Eisenhofer, who passed away on 27 July 2023, was one of the many émigré architects who came to New Zealand both pre and post World War Two and became known for their influence on the ‘International’ style in New Zealand’s design history.”