As you may have noticed, I’ve been doing less blogging lately, partly so that I can get more work done, and partly so that I can get more reading done too. I’m catching up on a few books I had bought but not yet read. One of these is Peter Beaven’s book about his own life and his substantial body of architectural work, Peter Beaven ARCHITECT.

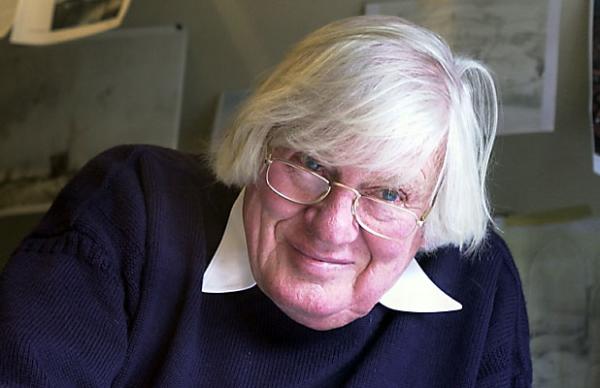

I had the pleasure of meeting Peter a few years before his death, and he was a lovely irascible old fellow, with a shock of white hair in an almost Andy Warhol style and a wit that cut right through to the bone, never missing an opportunity to get the knife into those who he thought were not up to scratch. That included most people of course, as Peter had incredible talent and never ceased being delighted to tell you that his buildings had outlasted Miles Warren’s buildings, etc. His book is not brilliantly written but it is indeed fascinating to read, anecdote sprinkled after anecdote, twinkling amusement after twinkling amusement, often about how Peter Beaven had saved the day – which of course, he always had. No false modesty here!

But one passage really caught my eye for what it said. Have a read of the following.

“My involvement with inner-city housing really began with a government committee which opened my eyes very wide indeed.

I spent a year in 1966 as the New Zealand Institute of Architects’ delegate on the government urban renewal committee with all the top people. There were the heads of the housing and planning departments; the many-times mayor of Auckland, Dove-Myer Robinson, and so on. Monthly meetings were held in Wellington. It showed me only too clearly the inability of central government committees ever to understand the complexity of contextual inner-city renewal.

As a working example, the government officials wanted to pull down the study area, Mount Victoria in Wellington, and replace the old heritage housing, which had been built over a hundred and fifty years, with star blocks of Ministry of Works design.

All over the hill, all that rich history of incremental streetscape was to be destroyed without any understanding of what they were really doing.

Incredibly, they had invited onto the committee experts from London council. These were the people who had recently pulled down the East End. We were meekly following along behind.

Sitting around the table were all the top planners in the private sector and the government, and all the people in the Ministry of Works with the most experience. I was shattered by all of this, and it made me realise how far away form the social and economic reality big government departments can get.

After months of meetings, the Ministry of Works was to produce its plan three days later. Sitting next to me was the Valuer-General, like me a generalist. He had a real distaste for this proposed economic madness and over a quiet cup of coffee I told him my plans to wander through Mount Victoria and plot what was really there. ‘I will support you,’ he said.

For three days and nights I stayed in Wellington and walked every inch of Mount Victoria, sketching the finest areas which were regenerating and gentrifying with real understanding, and finding also small pockets of decayed housing which could easily be infilled.

I put all this on three A4 sheets together with sketches of possible new infill housing and a written criticism of the housing department’s star flats and the destruction of the Mount Victoria area.

Around came the huge documentation from the housing department. Everyone approved simply automatically.

Then the Valuer-General said, ‘Before we approve this plan, Peter has drawn an alternative which I believe we must consider,’ and passed it around. Absolute silence.

Finally, out of the quiet, the housing minister said, ‘Let us add Peter’s plan to the end of the document as an alternative example of how it could be done.’ The document was then approved with my appendix, and the whole affair passed into swift oblivion, never to reappear anywhere.”

p141, “Inner-City Housing” in Peter Beaven ARCHITECT by Peter Beaven, pub Blenheim, 2016.

I’ve no reason to doubt its truthfulness, but I wonder if anyone knows that this happened? While the MoW’s Star flats are competent, they are barely world-breaking with excitement, and I for one am very glad that the MoW did not succeed in their plans. Mount Victoria’s cute, crazy, higgledy-piggledy housing is without doubt one of the chief reasons that Wellington is as photogenic as it is, and having lived there for many years I can testify that while they could undoubtedly be better planned for sunshine, they take full marks for enticing townscape. The prospect of Star flats all over the hillside does not fill me with enthralment – I doubt that anyone now would be lamenting the fact that this MoW came to fruition. While a Star flat might work on the flat, surrounded by green lawns and sunshine pouring in through both sides of the house, Mount Victoria is a curious place to propose them. Apart from the small sliver facing north over Oriental Bay, most of Mount Vic faces resolutely west, into the setting sun, and has abysmal prospects of early morning sunshine. Our flat had about 3 feet of back yard facing into the side of the hill, and then had a tiny front yard that fell away down towards the road. No sun till after midday, except for the sun that fell, uselessly, on the roof. A Star flat would not have been better, in any way, shape or form. The flat was architecturally terrible, but it was a much-loved home, and now I know that we can thank Peter Beaven that it was not removed.

Fair enough comment about their suitability for Mt Vic, but I have a soft spot for the Star flats and a deep sadness for all the ones in Moera/Seaview which have had their roofs ripped off and replaced with suburban gables. Interestingly, Star flats are at the centre of Mt Vic-level gentrification up in Freeman’s Bay – very chi-chi.

Starkive – yes, I’m not dissing the Stars, as I’ve never been in one, so I really can’t say. But on the face of it (admittedly only from the odd photo and drive-by), they would not have worked on Mt Vic at all. Are there any up in the provinces as well? Whanganui perchance?

Thanks for the interesting history Levi. Have a look at the various tower blocks in parts of Thorndon and Aro Valley.

I agree completely with you that these older wooden inner city suburbs are a critical part of the charm and character of Wellington.

Going back a few years we commissioned Graham McIndoe to assess the housing stock. The very clear finding was that there is a very high degree of consistency in terms of age – of course that doesn’t mean they are all the same – but in the mid to high 80%s of housing stock across Mt Victoria, Thorndon, Aro Valley, Mt Cook and Newtown were pre 1930 in age. They are of course also the place where most of what remains of the pre European indigenous forest of Wellington still remains. The Depression and War meant there was a significant drop of in building until post-1945 – so the contrast with the earlier building stock is very clear. It is not so much the individual buildings that are important but the coherence of the whole.

I was part of the District Plan hearings panel that (2 votes to 1) brought in the first pre 1930 non-demolition rule, meaning that you could not demolish as of right but had to show that a replacement building would enhance the surrounding environment (streetscape).

We subsequently brought in that pre 1930 rule across those inner suburbs. I believe it has played an important part in protecting that wonderful character.

Warmest regards

Andy Foster

Leader – Urban Development

Wellington City

Whanganui is well supplied with single-storey, single family state houses – some still state-owned even. Not much call for the Star blocks up this way. You can also get yourself a very nice Prairie bungalow for under $200,000 if you’re quick. River views a bit extra.