Here deep below the harbour waves at the Eye of the Fish, the recent discussion on Domes, Power, and the Judiciary set us thinking: What exactly is our self-image as reflected through our National architecture? Why do we have an emergent dome just peeking up out of a box, as a undefined symbol of our highest legal power? We had an extended discussion on symbols of power, mostly between M-D and Jayseatee, but a very telling quote comes from local commentator Honeywood:

I am intrigued by the dome, its burial in the podium, its cross-section and what all this says about our attitude to egalitarianism, justice and national identity. The dome is doubtless a grand volume but its submersion in the building is perhaps the most significant gesture of architectural and cultural denial I have seen in our national architecture, anywhere (although it is rivaled by Noel Lane’s inaccessible egg out the back of the Auckland Museum). Why, when we have the second most important civic building in the country do we diminish it so? Is this the ultimate in tall poppy fear? What would we risk by raising the dome, elevating it to a height appropriate to its function? Externally, the Supreme Court is proportionately the perfect podium in need of completion. WAM have positioned the dome post-earthquake. Where is the architectural courage when most we need it? We finally wrest supreme legal power from mother’s apron strings and then we ameliorate and reduce it.

We don’t have much of a neo-classical background on which to base our symbols of Judiciary, and while our Parliamentary hub looks like a Beehive, the metaphorical images within our nation’s architectural vocabulary seem to have dried up pretty quickly after that. Our national museum looks like… well, sadly, nothing much at all, except perhaps a mountain of mis-placed concrete planks, marooned on a asphalt island, waiting for a car race that will never come. Our national art gallery is… sadly missing, gone AWOL, presumed dead: subsumed within Te Papa’s ravaged hulking outline, lost on level 5. Our National Library currently looks like a giant inverted segmented pyramid, but is due to be re-imaged as an elusive fragmented parchment. Our proposed Supreme Court may look like a box of twigs or a post-modern birdsnest (is this implying, by its reference to a Box of Birds, that She’ll be Right ?); however the Sinbadian egghead at the heart of the Court has got us all wigged out, if not twigged right back. Perhaps its low browed dome is suitable as a response to the gently balding greying pates within, 5 judges in a row, pontificating on the highest matters of the land.

Domes are difficult to do well: Justinian’s architects Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus didn’t quite get it right with the domed roof of Santa Sophia in Constantinople, and the dome caved in during an earthquake: that’s a fairly serious claim on your PI insurance. Since then, angle of repose sorted out, domes have been a feature of many religious buildings, and indeed are often an architectural symbol of the religion concerned. Jews, Christians, Muslims, Seikhs, Buddhists: everyone likes a dome. Must be a God thing.

Meanwhile, other nations don’t feel quite so inhibited about the whole church / dome thing – after all, the Dome as an architectural feature (other than church) has been a constant amongst many cultures, some with more success than others. Let’s take a brief swim back in time, away from Rongotai and the airport, and by special Fish-travel back to France in the 18th century.

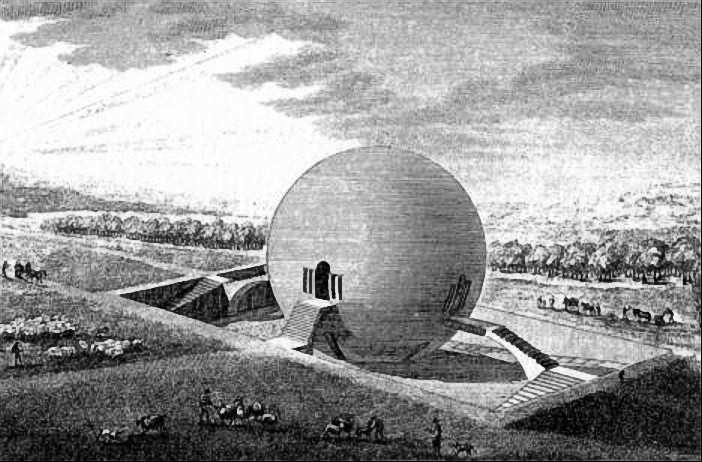

First up on any search for Domes must have to be Claude Nicolas Ledoux, the French neo-classical architect cum visionary: with his “House of the Gardener in an Ideal Town” (above). The Gardener’s House is a pretty tasty morsel of architectural mystery, but why would a gardener need to live in a dome only reachable by elaborate air-bridges? And if he’s the Gardener, why the big empty pit and the field of cows? Search me….

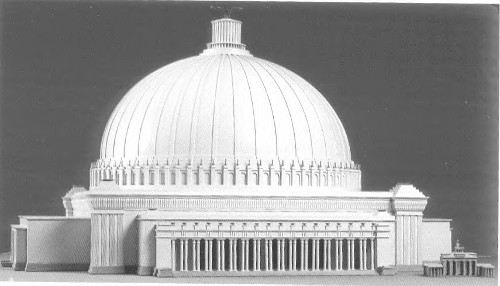

There’s a massive scale difference between the Ledoux home dome and the next Domic visionary, Etienne-Louis Boulee, with his monstrously sized “Monument to Isaac Newton” (below).

The monument for Newton is a huge structure 150m in diameter (shown with a ring of tall trees girdling its monumental girth), completely hollow inside and doubling as a planetarium by night. Lacking in a serious budget for the project, and no doubt subject to stringent ‘value engineering’ works, as well as suffering from the non-popular choice of an Englishman as the subject of a staunchly French monument, I’m guessing it’s likely that Boulee’s QS came up with an alternative solution to see the stars at night: just stand outside. Possibly predictably, it was never built.

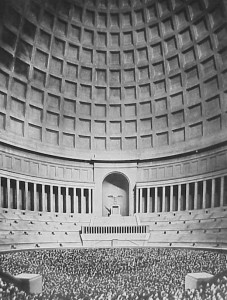

There is only one dome that I know of to beat that, and that of course was Albert Speer’s modest Hall of the People in his plans for post-war Berlin or Welthauptstadt (“world capital”) as his boss would have him call it (let’s not mention who he was working for).

Speer’s Volkshalle was to be the capital’s most important and impressive building in terms of size and symbolism. Visually, it was to have been the architectural masterpiece of Berlin as the world capital. Its dimensions were so large that it would have dwarfed every other structure in Berlin, include those on the north-south axis itself. The oculus of the building’s dome, 46 metres in diameter, would have accommodated the entire rotunda of Hadrian’s Pantheon and the dome of the St. Peter’s Basilica. The dome of the Volkshalle was to rise from a massive granite podium 315 by 315 metres and 74 metres high, to a total inclusive height of 290 metres.

So big in scale that clouds and a little rain may have formed inside the dome (for an idea of scale, look at the little grey portico on the bottom right: that is the Brandenburg Gate). The benefactor of Speer’s vision having gone the way of all crazed dictators, and Speer having been locked up in Spandau for decades, this dome was going nowhere either. Anyone might think you’d be planning to be around for a 1000 years or more… You can’t beat that for size or majesty, or even for sheer pomposity and outrageousness. Or can you?

The Brits, on the other hand, stunned the world recently by doing big, but barely beautiful, with the Millennium Dome (architect: Mike Davies at the Richard Rogers Partnership), a thin skin of teflon-coated fibreglass strung over a series of wires. I’m not sure how big it would be if it wasn’t sunk half way into the ground: as it is, the visible portion sticks up 50m, allegedly big enough to fit 18,000 double decker buses inside. So, it may have been a bigger diameter than Speer’s, although by comparison barely made it out of the ground. My rough calcs are that the Dome would have been around a kilometre in diameter if it had really been allowed to be a Dome, and not just a shallow, depressed, egghead.

Looking a little closer to reality, and spurred on by Jayseatee’s homeland and the American appropriation of a neoclassical base complete with dome as a symbol of both Statehood and Nationhood, we can look at America as the home of the Dome in a parliamentary sense, as opposed to the more European use of Dome as Church.

The Americans can do Domes with aplomb. Yes, they also have the AstroDome, the SuperDome, the Orange Bowl, etc: all paens to national sport – some open, some closed, but their true spirit comes through with a dome to democracy. Each State has its own Capitol, most (but not all, surely?) based on the original in Washington DC, of whom, you may be interested to know, there have been numerous steps along the way and thus numerous architects: William Thornton, Henry Latrobe, Charles Bullfinch, Thomas Walter. The Capitol in DC is very finely proportioned, and is a proudly resplendent symbol of the people of that country.

None of which, however, explains to me the attraction of installing our Supreme Judges in a dome so shallow that no one will see, from either the outside, or within. It’s a curious choice. 5 Judges sit inside, enjoying its Domishness. Or should that be Domesticity? TV cameras probably won’t be allowed inside, as the cases will be, gosh, just sooo important. School children will be scurrying around the perimeter, pretending to be Judges in the faithfully restored and historically moribund Court next door. Tourists and locals alike will be slowly circling the glass pavilion, behind the Box of Twigs, tapping on the eggshell surface, seeing if Horton will indeed hatch an egg.

Nice post…

Our Chief Justice, Sian Ellis is unlikely to be baring her dome in the dome though…

Can anyone else see the portrait in the large niche of the Speerian dome? creepy…

It’s probably the naivete of the non-architect, but something in me responds to formalist geometries as an expression of nationhood. My expression of appreciation for the solidity and scale of the big pile of concrete opposite the railway station was not intended as ironic. I found it very satisfying to walk around Washington and read the seriousness and significance of buildings in their density and scale and I quite fancy a bit of (suitably scaled) gravitas in Lower Thorndon.

However, I don’t think these qualities are intrinsically tied to neo-classicism and it seems to me that Niemeyer, Corbusier and others have long since shown that. I think the instantly recognisable form of the wharenui shows it. Why can’t we aspire to – and make – public buildings which communicate significance through form and situation without resorting to bombast or clip-on surfaces?

Just don’t call them “iconic”.

The Bouleé dome has always been my favourite architectural fantasy (along with some of the italian & russian futurists). I demand Wellington build it NOW!

On the notion of domes in the US, it should be noted that the US Capitol dome is not the original, which was far less impressive

Bullfinch Dome- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Capitol1846.jpg

As for the states, there are some interesting anomolies-

Bertram Goodhue (whom noone recognises now, but was a Frank Gehry of his time) did the unicameral Nebraska legislature building which is about as unlike the US capitol as possible.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nebraska_State_Capitol

The oregon state capitol is another oddity.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oregon_State_Capitol

There is a slightly misogynistic story about the colorado state capitol that I read in a history book about Denver.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colorado_State_Capitol

The dome was initially intended to have a statue at the top, similar to the US capitol.

The legislators of the day decided that the statue would be modeled after the most beautiful woman in the state.

They never could find one, so the dome remains without a statue. (In all likelihood it probably had more to do with the inability to agree over whose wife/mistress should be the model.)

M-D yes, I see that hitleresque face in that niche as well. Creepy.

Starkive-

you are quite right about niemeyer, while his city planning was abysmal he was able to create heroic buildings of national significance without invoking greek and roman ideals. In same ways I think timidity is the failure of public architecture in New Zealand. There is the potential to create something new, but few with the fortitude to push through truly provocative concepts.

I think this discussion is a very interesting one and I have one major underlying question to it, which is how much should the architecture reveal how power is developed?

In the most sincere reading of the US constitution the government is fundamentally constructed by the people. The power for it to exist is by public mandate. One of the interesting repurcussions (also due to our tripartite government) is that we don’t use the term “government” to refer to the ruling party. the majority party, the minority party, and all civil servants identify the “government”. Administrations change certianly, but the government is larger than personal or political party. The fact that “government” gets interchanged with the ruling party in New Zealand I find to be problematic in that it clearly states that those who are not within the in crowd have no say.

So what i’m curious about, is as the government is still an antiquated power of the queen (through her representative) to deem viable or not, does this not affect our entire notion of the symbolism of a national architecture? What excuse is their to have a face for a government when it in a sybmolic function symbolises nothing beyond party fealty?

A literal reading of our system would identify ‘parliament’ with what you describe as ‘government’ in the US – that is, it is made up of the major and minor parties, and is tasked with devising laws for this country. parliament is constructed by the people (as you put it), via both party and electorate votes in the general election.

The executive arm of our government is that which is aligned to party politics (although it has been common recently to have minor parties included in the executive) – what you would call the administration. This is determined via the party votes in the general election – thus, also by the people (in effect).

So, it is really an issue of semantics – we use the term ‘government’ to refer to the executive, but ‘parliament’ to refer to the legislative body. We will also use the term ‘government’ to more loosely refer to parliament, state services, etc as well…

But in practice, you are right – the executive retains control (through the weight of numbers on confidence and supply) of the parliament, even if MMP has helped to diversify that a little…

I forgot a few other anomolies of state capitols

Alaska

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaska_State_Capitol (nothing say bureaucratic quite like this)

Hawaii

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawaii_State_Capitol

Louisiana (similar to Nebraska)

http://www.nps.gov/history/NR/travel/louisiana/cap.htm

New York – Completely different from the normal capitol idea

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_State_Capitol

North Dakota

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Dakota_State_Capitol (ugh – like a glorified grain elevator)

Ohio

another non-domed structure

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ohio_Statehouse

Rhode island (5 times your dome pleasure)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhode_Island_State_House

Tennessee

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tennessee_State_Capitol

Virgina

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_State_Capitol

Clearly influenced by Jefferson’s monticello and UVA

Interesting, I had no idea how much variety there was until I did this.

New Mexico

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Mexico_State_Capitol

hmmm…. the silence is deafening.

perhaps new zealanders are complacent with cheap plastic footwear being the predominant national symbol? Maybe something along these lines?

and the link got dropped…

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Novelty_architecture

I think everyone is just pleasantly looking through your State Capitol links…. and i must say, while I’m taken with the very fetching North Dakota monolith (poor buggers), the Hawaiian Capitol building does have the most similarity to the NZ example.

I liked this as soon as I saw it…

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mulad/143093919/

But is there really nobody out there who can work with this?

http://www.ngatiwhare.iwi.nz/images/gallery/37827_ac_3_1.jpg

or this…

http://mp.natlib.govt.nz/detail/?id=30010&l=en

Yes, the Hawaiian one is interesting, i have to admit to knowing nothing about Hawaiian architecture, but from a cultural and historical perspective Hawaiian architecture would seem to be an intriguing counterpoint to NZ architecture (depite the tropical environment)

just wondering if someone can help me trying to remember something from 15 years ago.

In my intro to architecture class I remember the professor saying something like, “every domed structure in the world is based on 1 of 3 examples…” which I cannot remember.

I think the Pantheon, maybe the Florence Duomo..?

but then you have Hagia Sophia, and a variety of eastern architecture domed structures.

Which also doesn’t even make sense. Does that ring a bell to anyone? It’s like a fragment of a memory that has been blurred by not needing to know it in daily conversation and heavy amounts of alcohol.

New Zealand could take this old proposal for the US capitol. The scary thing on top could be either a really huge moa or maybe a taniwha or something.

again with the link…

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Capitol_design_by_james_diamond.jpg

The domesticity pun is unforgiveable

I think Ledoux’s dome is meant to resemble a pumpkin.

The Beehive is not only hideous but, more importantly, badly designed as regards function.

I would offer up the simple Vee as a more native symbol of Erewhon – two strong sticks lashed together in an inverted V and your Raupo hut is on its way – that same shape is everywhere from the ironside villas to early public buildings and if NZ has any kind of dome I’d say it is the semi-Oriental spire-like version that looks like a dome crossed with our distinctly steep gable – Berhampore has some extant examples.

Or how about if these domes of Maximus’ reverie* were to follow the penneplain shape of our local hills – the top shaved off by wave action in our underwater past?

Rising steeply up then flattening off at the top may look a little like a Dr Suess illustration but so did the field of Cabbage trees encountered on the road to Cape Palliser last weekend.

*No boob jokes Maximus – remember you’re a fish..

“- remember you’re a fish..” – I can’t forget it. The delicate shape of a young herring’s flipper, the lithe shape of a marlin’s thigh…

Starkive – I think the model of a pataka as a Supreme Court might be pushing the indigenous metaphor a little too far. And wouldn’t reference to pre-European contact architecture run the risk of saying rather inaccurate things about who is destined to make the most use of the building…

I’ve been doing some of my own research into the secret to the use of domes in architecture – see here: http://acwp.thanh.co.nz/2009/03/31/video-of-the-week-xi-architecture-energy-1/

jayseatee – perhaps it was St Peter’s in Rome? In any event, your lecturer does sound rather Eurocentric, and somewhat ‘antique’ at the same time, given both the plethora of domes in other cultures, and the presence of more recent archetypes from the last half decade or so…

http://www.columbia.edu/cu/gsapp/BT/DOMES/TIMELN/rome_sm/rs17-01.jpg

http://realneo.us/system/files/dome2.jpg

http://www.bearsac.com/Germany/Germany.ReichstagDome.JPG

etc…

I’m not sure that indigeneity is metaphorical.

I was looking for a more literal reading. Not so much from the pataka, which is probably a better connection with a national museum/gallery, but with the wharenui which is pretty darn appropriate.

“I was looking for a more literal reading.”

So, then… the Supreme Court becomes the body of ‘our’ ancestors then… which ones did you have in mind in particular…? …Good luck selling that to the masses…

The point is, however, that the Supreme Court is a NZ institution, not an exclusively Maori one. That is not to say that it shouldn’t accommodate and respect Maori cultural beliefs and traditions, but that these shouldn’t be employed in a superficial way to stand in for the idea of ‘kiwi’ culture more generally – especially when you are just borrowing forms and motifs without the cultural/spiritual significance that is inherent to them… I thought we might have got past Pakeha appropriation of Maori forms and traditions in this inappropriate way (i.e. a stylistic appropriation such as the modern moko tattoos (see Robbie Williams), Air NZ logo, the haka, etc)…

PS – I’ve always found the pataka – museum/gallery metaphor to be somewhat tenuous, to say the least…

interesting M-D,

and quite amazing and naive that the commentator missed the freudian connection to towers with domes indicating a channel of power…

Reading your post m-d, you seem to be describing a “we” which does not include Maori. I think you should ask some Maori if they feel that the employment of Maori forms and traditions in “our” public architecture would be appropriational. And on the question of “getting past it”, you might then ask if they have ever seen it done in a structural rather than decorative way. It’s a bit hard to argue that an approach that has never been tried has become old hat.

If you think that a Supreme Court building based on 60MPa’s “inverted V” would somehow denote an exclusively Maori institution and hence alienate some of “us”, imagine what it must have been like for generation after generation of Maori seeing New Zealand’s public life being conducted in Greek temples and Northern European castles.

To reject the possibility of working with the characteristic forms of Maori architecture on the grounds that they do not encompass the totality of our immigrant origins must surely also lead us to exclude Greek, Roman, Gothic EuroModernist and all other off-shore forms too. Which would leave us with…?

are historic maori and other pasifika architectural forms any more relevant to contemporary maori and pasifika peoples than John Soane is to contemporary pakeha?

starkive – I explicitly stated in my response: “That is not to say that it shouldn’t accommodate and respect Maori cultural beliefs and traditions” – so I am unsure of how you think my ‘we’ is exclusive of Maori culture. And, I’m not buying into 60MPA’s solution for that matter either…

As for Maori consultation, sure, I agree; but there has already been much resistance to cultural appropriation (as one would expect)… It is more than a simplistic structural vs decorative issue as well – with cultural/spirituality at stake (which I indicated above, but you seem to have ignored), so i am arguing that your proposed solution is exactly that which has been rejected by Maori in other fields as cultural appropriation – so yeah, kind of old hat… (not to mention that the type of exploration you refer to has been experimented with by various architects seeking an indigenous architecture – with varying results…)

I am certainly not against Maori concepts informing the design where appropriate (and would in fact encourage it), but think that referencing past Maori built forms in a superficial way is a tired and inappropriate strategy. There is a place for contemporary interpretations of the Wharenui form, which include all functions of the building (and that includes the ‘functions’ that exist beyond the Pakeha sense of pragmatics) – I don’t see the Supreme Court as one of them, nor the idea of an iconic national architectural symbol that your last paragraph seems to imply that we are seeking here…

There is, as always, a middle road, less travelled than either the great trek of drek that is the mock-neo-classical greek temple proforma, or the mock-tangata whenua open arms of the whare in its many forms.

I feel that both are dodgy precedents to be following. Both are beset by cultural cringe and inaccurate / inauthentic followings. I’d suggest that John Scott has more relevance to either culture than John Soane, but the traditional model of the maori whare that Starkive has illustrated (nice pix / links, thanks) tends to be either incredibly well done (ie totally authentic carving, fingers, precedents, backbone etc) or really nastily short-cutted (vague suggestion of a bargeboard, compromised by innapropriate support points etc).

The middle ground, shown by the sensitivity to both cultures shown by Scott at Futuna and Urewera, and in his housing generally, is the basis of a route that domestic housing could (arguably should) follow, but does not deal so well with more major public buildings. However – what if we took as our example the Jean Tjibou (sp?) Centre in New Caledonia, where the traditional form was taken and extrapolated into a major dynamic new shape and form.

It is, I think, what WAM have tried to do with the Supreme Court – but arguably not achieved. The form is perhaps too rigid, too rectangular, too extruded: too cast in bronze to allow a more flexible response to the brief. But then again, there are only going to be 5 elderly people in there, a few times a year. The building is more ceremonial than it is purposeful.

Jayseatee – perhaps you can answer this: what do people actually do inside these capitol domes? Is it a vast Hitlerian rallying point, or is it just a flat ceiling and some dreary offices under each one?

“the type of exploration you refer to has been experimented with by various architects seeking an indigenous architecture – with varying results…”

Love to see some links – especially in non-domestic contexts.

starkive – that’s a tough task, as I did have domestic and religious architecture in mind rather than public architecture – including Richard Toy’s All Saints in Auckland, and particularly John Scott. Scott’s use of Maori forms and motifs (both ‘structural’ and decorative) leave me someone bemused – they are clearly compelling, but somewhat meaningless in his use of them – mind you, he always refused the label of ‘Maori architect’ (whatever that might mean)…

Our larger projects seem to be more enamoured with US Modernism however… I’ll ponder it though…

Maximus – there are enough images in the link below to indicate the domed glory of the spaces in question – however, you do need to wade through them to see more of the interior than just the domes themselves…

http://www.flickr.com/search/?q=capitol+interior+dome&ss=2&s=int

yes, that is the irony of the dome, they are in most capitol buildings, actually unoccupied. They are not programmed space, other than “rotunda”. The usual activity is a gaggle of tourists eyes to the heavens with cameras in hand saying “wow…look at that dome.”

Tying it back to the religious connotation that you first started with, it could be seen as deeply heretical – the cathedrals drew your eyes upward to god to be amazed and overwhelmed, so for a public building to do so could be argued to be inappropriate. However for the foundation of the US, where a secular society was to be established the concept of looking upward and acknowledging that the collective governance was what it symbolised was quite strong. Considering that Jefferson took his scissors to the old king james and rearranged it more to his liking and personal philosophy, i could see the sublimation of religious concepts as a legitimate interpretation.

along the lines of M-D’s video here is a symbolic building that has some definite creepiness going on. This is the Masonic Temple in Alexandria, VA, just across the river to the south from washington, DC.

http://media-cdn.tripadvisor.com/media/photo-s/01/06/4f/30/george-washington-national.jpg

As you can see it’s quite a tall, probably 10 t0 12 standard storeys. However it’s actually only 5 rooms stacked on top of each other, with some hieararchical gibberish about who is allowed into each room.

and at the top? A pyramid!

cue one of my favourite references.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NBav72i7I3s

actually there’s some interesting stuff about the masonic temple here:

http://www.gwmemorial.org/index.php#

I had always heard only the ground floor was open to the public, but it appears upper floors are open as well.

Maximus, I was thinking of the Caledonian Centre whilst reading this thread and I think it’s a damn fine work – particularly the idea of a series of huts along the common village path – a private view out but community right outside your door

http://www.pbase.com/tanetahi/tjibaou

M – D, I only got as far into the embedded video as the mention of “Stargate” at which point my BSF (Bad Sci-Fi) alarm went off and I had to hit the dump button. There were some good points made nonetheless about the favoured symbolic forms but please, there’s only so many shapes available before we get into isodecahedrawhotsits so wouldn’t some repetition be excusable?

I agree that one has to be there to see them properly though – pictures do little justice.

The idea of an inverted V was merely that it struck me as one of the few shapes I had seen in both european (villa gables) and maori buildings eg

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TePuia.2.JPG

Jayseatee, those lifts in the Washington building are wild – typical Masons, always with the bloody triangles. Anyone know how many Surveyors are in the brotherhood?

Some domes are terribly useful

http://jamestamp.com/2005/03/amazing-inflatable-concrete-building.html

and, as ever, our Statesider friends go all out

http://static.monolithic.com/plan-design/monolithicdome/index.html

Now if only they’d made the Supreme Court as a Torus with one end raised we could have had a rather interesting skatepark as well

The use of the Pataka as architectural icon is spreading already… in many guises. Take your children this weekend to the Dowse to see their take:

http://www.newdowse.org.nz/Events/Events/Bouncy-Marae/